Related Research Articles

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure," and may also be referred to as simply a flake, or collectively as debitage. The objective piece, or the rock being reduced by the removal of flakes, is known as a core. Once the proper tool stone has been selected, a percussor or pressure flaker is used to direct a sharp blow, or apply sufficient force, respectively, to the surface of the stone, often on the edge of the piece. The energy of this blow propagates through the material, often producing a Hertzian cone of force which causes the rock to fracture in a controllable fashion. Since cores are often struck on an edge with a suitable angle (<90°) for flake propagation, the result is that only a portion of the Hertzian cone is created. The process continues as the flintknapper detaches the desired number of flakes from the core, which is marked with the negative scars of these removals. The surface area of the core which received the blows necessary for detaching the flakes is referred to as the striking platform.

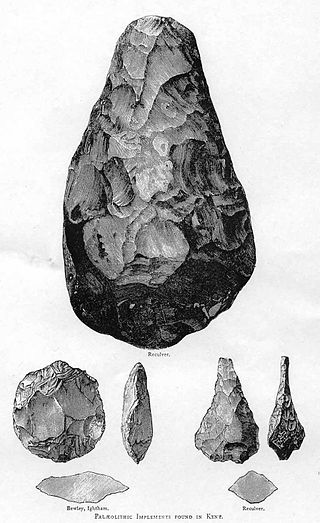

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric cultures that have become extinct. Archaeologists often study such prehistoric societies, and refer to the study of stone tools as lithic analysis. Ethnoarchaeology has been a valuable research field in order to further the understanding and cultural implications of stone tool use and manufacture.

Experimental archaeology is a field of study which attempts to generate and test archaeological hypotheses, usually by replicating or approximating the feasibility of ancient cultures performing various tasks or feats. It employs a number of methods, techniques, analyses, and approaches, based upon archaeological source material such as ancient structures or artifacts.

In archaeology, ground stone is a category of stone tool formed by the grinding of a coarse-grained tool stone, either purposely or incidentally. Ground stone tools are usually made of basalt, rhyolite, granite, or other cryptocrystalline and igneous stones whose coarse structure makes them ideal for grinding other materials, including plants and other stones.

In archaeology, lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level, lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact's morphology, the measurement of various physical attributes, and examining other visible features.

An artifact or artefact is a general term for an item made or given shape by humans, such as a tool or a work of art, especially an object of archaeological interest. In archaeology, the word has become a term of particular nuance and is defined as an object recovered by archaeological endeavor, which may be a cultural artifact having cultural interest.

In archaeology, a denticulate tool is a stone tool containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes, much like the toothed edge of a saw. Such tools have been used as saws for woodworking, processing meat and hides, craft activities and for agricultural purposes. Denticulate tools were used by many different groups worldwide and have been found at a number of notable archaeological sites. They can be made from a number of different lithic materials, but a large number of denticulate tools are made from flint.

In archaeology, a blade is a type of stone tool created by striking a long narrow flake from a stone core. This process of reducing the stone and producing the blades is called lithic reduction. Archaeologists use this process of flintknapping to analyze blades and observe their technological uses for historical purposes.

Archaeological ethics refers to the moral issues raised through the study of the material past. It is a branch of the philosophy of archaeology. This article will touch on human remains, the preservation and laws protecting remains and cultural items, issues around the globe, as well as preservation and ethnoarchaeology.

In archaeology, lithic technology includes a broad array of techniques used to produce usable tools from various types of stone. The earliest stone tools to date have been found at the site of Lomekwi 3 (LOM3) in Kenya and they have been dated to around 3.3 million years ago. The archaeological record of lithic technology is divided into three major time periods: the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic. Not all cultures in all parts of the world exhibit the same pattern of lithic technological development, and stone tool technology continues to be used to this day, but these three time periods represent the span of the archaeological record when lithic technology was paramount. By analysing modern stone tool usage within an ethnoarchaeological context, insight into the breadth of factors influencing lithic technologies in general may be studied. See: Stone tool. For example, for the Gamo of Southern Ethiopia, political, environmental, and social factors influence the patterns of technology variation in different subgroups of the Gamo culture; through understanding the relationship between these different factors in a modern context, archaeologists can better understand the ways that these factors could have shaped the technological variation that is present in the archaeological record.

Use-wear analysis is a method in archaeology to identify the functions of artifact tools by closely examining their working surfaces and edges. It is mainly used on stone tools, and is sometimes referred to as "traceological analysis".

Harold Lewis Dibble was an American Paleolithic archaeologist. His main research concerned the lithic reduction during which he conducted fieldwork in France, Egypt, and Morocco. He was a professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and Curator-in-Charge of the European Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Peter Dixon Hiscock is an Australian archaeologist. Born in Melbourne, he obtained a PhD from the University of Queensland. Between 2013 and 2021, he was the inaugural Tom Austen Brown Professor of Australian Archaeology at the University of Sydney, having previously held a position in the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University.

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes. Archaeology can be considered both a social science and a branch of the humanities. It is usually considered an independent academic discipline, but may also be classified as part of anthropology, history or geography.

Chaîne opératoire is a term used throughout anthropological discourse, but is most commonly used in archaeology and sociocultural anthropology. It functions as a methodological tool for analysing the technical processes and social acts involved in the step-by-step production, use, and eventual disposal of artifacts, such as lithic reduction or pottery. This concept of technology as the science of human activities was first proposed by French archaeologist, André Leroi-Gourhan, and later by the historian of science André-Georges Haudricourt. Both were students of Marcel Mauss who had earlier recognised that societies could be understood through its techniques by virtue of the fact that operational sequences are steps organised according to an internal logic specific to a society.

The Kalinga Ethnoarchaeological Project (KEP), based in the Cordillera Mountains of the Philippines, was one of the longest-running ethnoarchaeological projects in the world. It was initiated by William Longacre, professor at the University of Arizona, in 1973. Lasting for almost 20 years, research focused on pottery production, use, exchange, and discard, and was carried out by Longacre and his team of Kalinga assistants, archaeology students, and colleagues.

James M. Skibo was an American archaeologist who was the State Archaeologist of Wisconsin from 2021 to 2023. His archaeological research focused on the production and use of ceramics as well as the theory of archaeology and ethnoarchaeology. He was mainly concerned with the Great Lakes, the Southwest United States, and the Philippines.

Behavioural archaeology is an archaeological theory that expands upon the nature and aims of archaeology in regards to human behaviour and material culture. The theory was first published in 1975 by American archaeologist Michael B. Schiffer and his colleagues J. Jefferson Reid, and William L. Rathje. The theory proposes four strategies that answer questions about past, and present cultural behaviour. It is also a means for archaeologists to observe human behaviour and the archaeological consequences that follow.

Carol Kramer was an American archaeologist known for conducting ethnoarchaeology research in the Middle East and South Asia. Kramer also advocated for women in anthropology and archaeology, receiving the Squeaky Wheel Award from the Committee on the Status of Women in Anthropology in 1999. Kramer co-wrote Ethnoarchaeology in Action (2001) with Nicolas David, the first comprehensive text on ethnoarchaeology, and received the Award for Excellence in Archaeological Analysis posthumously in 2003.

Brian Douglas Hayden is an American ethno-archaeologist prominent in research in North and Central America and Australia.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Lane, Paul. Barbarous Tribes and Unrewarding Gyration? The Changing Role of Ethnographic Imagination in African Archaeology. Blackwell.

- ↑ Stiles, Daniel (1977). "Ethnoarchaeology: A Discussion of Methods and Applications". Man. 12 (1): 87–89. doi:10.2307/2800996. JSTOR 2800996.

- ↑ Fewkes, Jesse (1901). Tusayan Migration Traditions. Washington: Washington Government Printing Office. p. 579 . Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ↑ David, Nicholas; Kramer, Carol (2001). Ethnoarchaeology in action (Digitally repr., with corr. ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–31. ISBN 978-0521667791.

- 1 2 3 Ascher, Robert (Winter 1961). "Analogy in Archaeological Interpretation". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 17 (4): 317–325. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.17.4.3628943. JSTOR 3628943.

- ↑ McCall, G. S. (2012). Ethnoarchaeology and the organization of lithic technology. Journal of Archaeological Research, 20(2), 157-203.

- ↑ Gould, R. A.; Koster, D. A.; Sontz, H. L. (1971). "The Lithic Assemblage of the Western Desert Aborigines of Australia". American Antiquity. 36 (2): 149–169. doi:10.2307/278668. JSTOR 278668.

- ↑ Gould, Richard; Koster, Dorothy; Sontz, Ann (1971). "The Lithic Assemblage of the Western Desert Aborigines of Australia". American Antiquity. 36 (2): 149–169. doi:10.2307/278668. JSTOR 278668.