Cladonia rangiferina, also known as reindeer cup lichen, reindeer lichen or grey reindeer lichen, is a light-coloured fruticose, cup lichen species in the family Cladoniaceae. It grows in both hot and cold climates in well-drained, open environments. Found primarily in areas of alpine tundra, it is extremely cold-hardy.

Usnea is a genus of mostly pale grayish-green fruticose lichens that grow like leafless mini-shrubs or tassels anchored on bark or twigs. The genus is in the family Parmeliaceae. It grows all over the world. Members of the genus are commonly called old man's beard, beard lichen, or beard moss.

Oakmoss is a species of lichen. It can be found in many mountainous temperate forests throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Oakmoss grows primarily on the trunk and branches of oak trees, but is also commonly found on the bark of other deciduous trees and conifers such as fir and pine. The thalli of oakmoss are short and bushy, and grow together on bark to form large clumps. Oakmoss thallus is flat and strap-like. They are also highly branched, resembling the form of antlers. The colour of oakmoss ranges from green to a greenish-white when dry, and dark olive-green to yellow-green when wet. The texture of the thalli is rough when dry and rubbery when wet. It is used extensively in modern perfumery.

Traditional dyes of the Scottish Highlands are the native vegetable dyes used in Scottish Gaeldom.

The Parmeliaceae is a large and diverse family of Lecanoromycetes. With over 2700 species in 71 genera, it is the largest family of lichen-forming fungi. The most speciose genera in the family are the well-known groups: Xanthoparmelia, Usnea, Parmotrema, and Hypotrachyna.

Pseudevernia furfuracea, commonly known as tree moss, is a lichenized species of fungus that grows on the bark of firs and pines. The lichen is rather sensitive to air pollution, its presence usually indicating good air conditions in the growing place. The species has numerous human uses, including use in perfume, embalming and in medicine. Large amounts of tree moss is annually processed in France for the perfume industry.

Orcein, also archil, orchil, lacmus and C.I. Natural Red 28, are names for dyes extracted from several species of lichen, commonly known as "orchella weeds", found in various parts of the world. A major source is the archil lichen, Roccella tinctoria. Orcinol is extracted from such lichens. It is then converted to orcein by ammonia and air. In traditional dye-making methods, urine was used as the ammonia source. If the conversion is carried out in the presence of potassium carbonate, calcium hydroxide, and calcium sulfate, the result is litmus, a more complex molecule. The manufacture was described by Cocq in 1812 and in the UK in 1874. Edmund Roberts noted orchilla as a principal export of the Cape Verde islands, superior to the same kind of "moss" found in Italy or the Canary Islands, that in 1832 was yielding an annual revenue of $200,000. Commercial archil is either a powder or a paste. It is red in acidic pH and blue in alkaline pH.

Litmus is a water-soluble mixture of different dyes extracted from lichens. It is often absorbed onto filter paper to produce one of the oldest forms of pH indicator, used to test materials for acidity. In an acidic medium, blue litmus paper turns red, while in a basic or alkaline medium, red litmus paper turns blue. In short, it is a dye and indicator which is used to place substances on a pH scale.

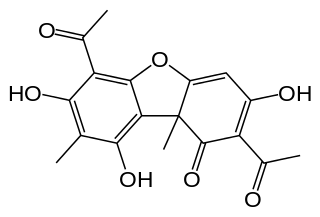

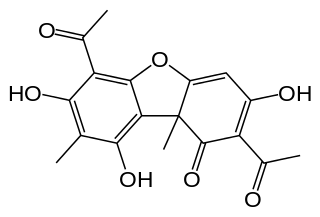

Usnic acid is a naturally occurring dibenzofuran derivative found in several lichen species with the formula C18H16O7. It was first isolated by German scientist W. Knop in 1844 and first synthesized between 1933 and 1937 by Curd and Robertson. Usnic acid was identified in many genera of lichens including Usnea, Cladonia, Hypotrachyna, Lecanora, Ramalina, Evernia, Parmelia and Alectoria. Although it is generally believed that usnic acid is exclusively restricted to lichens, in a few unconfirmed isolated cases the compound was found in kombucha tea and non-lichenized ascomycetes.

Henry Edward Schunck, also known as Edward von Schunck, was a British chemist who did much work with dyes.

Cetraria is a genus of fruticose lichens that associate with green algae as photobionts. Most species are found at high latitudes, occurring on sand or heath. Species have a characteristic "strap-like" form, with spiny lobe edges.

Bryoria fremontii is a dark brown, horsehair lichen that grows hanging from trees in western North America, and northern Europe and Asia. It grows abundantly in some areas, and is an important traditional food for a few First Nations in North America.

The Roccellaceae are a family of mostly lichen-forming fungi in the order Arthoniales, established by the French botanist François Fulgis Chevallier in 1826. Species in the family exhibit various growth forms, including crustose and fruticose (shrub-like) thalli, and diverse reproductive structures. Roccellaceae species typically have disc-like or slit-like fruiting bodies, often with distinct blackened margins. Molecular phylogenetics studies have revealed considerable genetic diversity and complex evolutionary histories within the family.

Letharia vulpina, commonly known as the wolf lichen, is a fruticose lichenized species of fungus in the family Parmeliaceae. It is bright yellow-green, shrubby and highly branched, and grows on the bark of living and dead conifers in parts of western and continental Europe and the Pacific Northwest and northern Rocky Mountains of North America. This species is somewhat toxic to mammals due to the yellow pigment vulpinic acid, and has been used historically as a poison for wolves and foxes. It has also been used traditionally by many native North American ethnic groups as a pigment source for dyes and paints.

Edible lichens are lichens that have a cultural history of use as a food. Although almost all lichen are edible, not all have a cultural history of usage as an edible lichen. Often lichens are merely famine foods eaten in times of dire needs, but in some cultures lichens are a staple food or even a delicacy. Some lichens are a source of vitamin D.

Parmotrema perlatum, commonly known as the powdered ruffle lichen, is a common species of foliose lichen in the family Parmeliaceae. The species has a cosmopolitan distribution and occurs throughout the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Parmotrema perlatum is a prominent and widely recognised species within its genus across primarily temperate zones, preferring humid, oceanic-suboceanic habitats. It is found in diverse geographic areas including Africa, North and South America, Asia, Australasia, Europe, and islands in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It usually grows on bark, but occasionally occurs on siliceous rocks, often among mosses.

Cladonia stellaris or the star-tipped cup lichen is an ecologically important species of cup lichen that forms continuous mats over large areas of the ground in boreal and arctic regions around the circumpolar north. The species is a preferred food source of reindeer and caribou during the winter months, and it has an important role in regulating nutrient cycling and soil microbiological communities. Like many other lichens, Cladonia stellaris is used by humans directly for its chemical properties, as many of the secondary metabolites are antimicrobial, but it also has the unique distinction of being harvested and sold as 'fake trees' for model train displays. It is also used as a sound absorber in interior design. The fungal portion of Cladonia stellaris, known as a mycobiont, protects the lichen from lichenivores, superfluous solar radiation, and other kinds of stressors in their ecosystem.

Lichens of the Sierra Nevada have been little studied. A lichen is a composite organism consisting of a fungus and a photosynthetic partner growing together in a symbiotic relationship.

Lichen products, also known as lichen substances, are organic compounds produced by a lichen. Specifically, they are secondary metabolites. Lichen products are represented in several different chemical classes, including terpenoids, orcinol derivatives, chromones, xanthones, depsides, and depsidones. Over 800 lichen products of known chemical structure have been reported in the scientific literature, and most of these compounds are exclusively found in lichens. Examples of lichen products include usnic acid, atranorin, lichexanthone, salazinic acid, and isolichenan, an α-glucan. Many lichen products have biological activity, and research into these effects is ongoing.