Related Research Articles

The Council of the European Union, often referred to in the treaties and other official documents simply as the Council, and informally known as the Council of Ministers, is the third of the seven Institutions of the European Union (EU) as listed in the Treaty on European Union. It is one of two legislative bodies and together with the European Parliament serves to amend and approve or veto the proposals of the European Commission, which holds the right of initiative.

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957, aiming to foster economic integration among its member states. It was subsequently renamed the European Community (EC) upon becoming integrated into the first pillar of the newly formed European Union in 1993. In the popular language, however, the singular European Community was sometimes inaccurately used in the wider sense of the plural European Communities, in spite of the latter designation covering all the three constituent entities of the first pillar.

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union, it adopts European legislation, following a proposal by the European Commission. The Parliament is composed of 705 members (MEPs), due to rise to 720 after the June 2024 European elections. It represents the second-largest democratic electorate in the world, with an electorate of 375 million eligible voters in 2009.

The European Council is a collegiate body that defines the overall political direction and priorities of the European Union. The European Council is part of the executive of the European Union (EU), beside the European Commission. It is composed of the heads of state or of government of the EU member states, the President of the European Council, and the President of the European Commission. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy also takes part in its meetings.

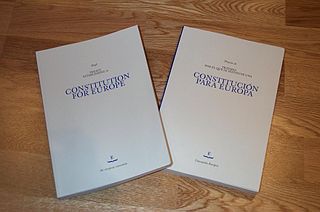

The Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe was an unratified international treaty intended to create a consolidated constitution for the European Union (EU). It would have replaced the existing European Union treaties with a single text, given legal force to the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and expanded qualified majority voting into policy areas which had previously been decided by unanimity among member states.

The presidency of the Council of the European Union is responsible for the functioning of the Council of the European Union, which is the co-legislator of the EU legislature alongside the European Parliament. It rotates among the member states of the EU every six months. The presidency is not an individual, but rather the position is held by a national government. It is sometimes incorrectly referred to as the "president of the European Union". The presidency's function is to chair meetings of the council, determine its agendas, set a work program and facilitate dialogue both at Council meetings and with other EU institutions. The presidency is currently, as of January 2024, held by Belgium.

A European political party, known formally as a political party at European level and informally as a European party or a Europarty, is a type of political party organisation operating transnationally in Europe and within the institutions of the European Union (EU). They are regulated and funded by EU Regulation 1141/2014 on the statute and funding of European political parties and European political foundations, and their operations are supervised by the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations (APPF). European political parties – mostly consisting of national member parties, and few individual members – have the right to campaign during the European elections, for which they often adopt manifestos outlining their positions and ambitions. Ahead of the elections, some of them designate their preferred candidate to be the next President of the European Commission.

The institutions of the European Union are the seven principal decision-making bodies of the European Union and the Euratom. They are, as listed in Article 13 of the Treaty on European Union:

The political structure of the European Union (EU) is similar to a confederation, where many policy areas are federalised into common institutions capable of making law; the competences to control foreign policy, defence policy, or the majority of direct taxation policies are mostly reserved for the twenty-seven state governments. These areas are primarily under the control of the EU's member states although a certain amount of structured co-operation and coordination takes place in these areas. For the EU to take substantial actions in these areas, all Member States must give their consent. Union laws that override State laws are more numerous than in historical confederations; however, the EU is legally restricted from making law outside its remit or where it is no more appropriate to do so at a state or local level (subsidiarity) when acting outside its exclusive competences. The principle of subsidiarity does not apply to areas of exclusive competence.

Monica Frassoni is an Italian politician who served as a Member of the European Parliament from 1999 to 2009 and as co-chair of the European Green Party from 2009 to 2019. In 2018, she was elected at the local Council of Ixelles in the Brussels Region, representing the Ecolo party.

The consent procedure is one of the special legislative procedures of the European Union. Introduced by the Single European Act, under this procedure, the Council of the European Union must obtain the European Parliament's consent (assent) before certain decisions can be made. Acceptance (consent) requires an absolute majority of votes in Parliament.

The European Union adopts legislation through a variety of legislative procedures. The procedure used for a given legislative proposal depends on the policy area in question. Most legislation needs to be proposed by the European Commission and approved by the Council of the European Union and European Parliament to become law.

Government procurement or public procurement is undertaken by the public authorities of the European Union (EU) and its member states in order to award contracts for public works and for the purchase of goods and services in accordance with principles derived from the Treaties of the European Union. Such procurement represents 13.6% of EU GDP as of March 2023, and has been the subject of increasing European regulation since the 1970s because of its importance to the European single market.

The Treaty of Lisbon is an international agreement that amends the two treaties which form the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU). The Treaty of Lisbon, which was signed by all EU member states on 13 December 2007, entered into force on 1 December 2009. It amends the Maastricht Treaty (1992), known in updated form as the Treaty on European Union (2007) or TEU, as well as the Treaty of Rome (1957), known in updated form as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2007) or TFEU. It also amends the attached treaty protocols as well as the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM).

Electronic evidence consists of these two sub-forms:

Lobbying in the European Union, also referred to officially as European interest representation, is the activity of representatives of diverse interest groups or lobbies who attempt to influence the executive and legislative authorities of the European Union through public relations or public affairs work. The Treaty of Lisbon introduced a new dimension of lobbying at the European level that is different from most national lobbying. At the national level, lobbying is more a matter of personal and informal relations between the officials of national authorities, but lobbying at the European Union level is increasingly a part of the political decision-making process and thus part of the legislative process. 'European interest representation' is part of a new participatory democracy within the European Union. The first step towards specialised regulation of lobbying in the European Union was a Written Question tabled by Alman Metten, in 1989. In 1991, Marc Galle, Chairman of the Committee on the Rules of Procedure, the Verification of Credentials and Immunities, was appointed to submit proposals for a Code of conduct and a register of lobbyists. Today lobbying in the European Union is an integral and important part of decision-making in the EU. From year to year lobbying regulation in the EU is constantly improving and the number of lobbyists is increasing.

Events in the year 1993 in the European Union.

The European Union's (EU) Common Commercial Policy, or EU Trade Policy, is the policy whereby EU Member States delegate authority to the European Commission to negotiate their external trade relations, with the aim of increasing trade amongst themselves and their bargaining power vis-à-vis the rest of the world. The Common Commercial Policy is logically necessitated by the existence of the Customs Union, which in turn is also the foundation upon which the Single Market and Monetary Union were later established.

The Conference on the Future of Europe was a proposal of the European Commission and the European Parliament, announced at the end of 2019, with the aim of looking at the medium- to long-term future of the EU and what reforms should be made to its policies and institutions. It is intended that the Conference should involve citizens, including a significant role for young people, civil society, and European institutions as equal partners and last for two years. It will be jointly organised by the European Parliament, the EU Council and the European Commission. On 19 April 2021, the multilingual digital platform of the Conference futureu.europa.eu was launched.

Opposition is a fundamental element of democracy. Without the right to challenge and criticise ones government, its policies and its actions, democracy cannot develop. Political opposition, “ when B is opposed to the conduct of government A", can include opposition from parties not in government, as well as actors other than political parties.

References

- ↑ "Interinstitutional Negotiations". European Parliament. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ↑ Panning, Lara (2020). "Building and managing the European Commission's position for trilogue negotiations". Journal of European Public Policy. 28 (1): 32–52. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1859597.

- ↑ "Interinstitutional Negotiations". European Parliament. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ↑ "Trilogue". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ "One Pager: Trilogue Consultation". European Movement International. 10 November 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ↑ "Rules of Procedure". European Parliament. Retrieved 2 May 2024.Title II, ch. 3, s. 3.

- ↑ "The ordinary legislative procedure". European Council and Council of the European Union. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ↑ "What are trilogues?". European Crypto Initiative. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ "Interinstitutional negotiations". European Parliament. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ "What are trilogues?". European Crypto Initiative. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ Brandsma, Gijs Jan (2015). "Co-decision after Lisbon: The politics of informal trilogues in European Union lawmaking". European Union Politics. 16 (2): 300–319. doi:10.1177/1465116515584497.

- ↑ Brandsma, Gijs Jan (2021). "Inside the black box of trilogues: introduction to the special issue". Journal of European Public Policy. 28 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1859600. hdl: 2066/229227 .

- ↑ "Activity Report on the ordinary legislative procedure 2014-2019" (PDF). European Parliament. Retrieved 3 May 2024. p. 10.

- ↑ "Activity Report on the ordinary legislative procedure 2014-2019" (PDF). European Parliament. Retrieved 3 May 2024. p. 9.

- ↑ "Trilogues: the system that undermines EU democracy and transparency". European Digital Rights. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ Brandsma, Gijs Jan (2021). "Inside the black box of trilogues: introduction to the special issue". Journal of European Public Policy. 28 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1859600. hdl: 2066/229227 .

- ↑ "What are trilogues?". European Crypto Initiative. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ Greenwood, Justin (2021). "Organized interests and trilogues in a post-regulatory era of EU policy-making". Journal of European Public Policy. 28 (1): 112–131. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1859592. pp. 117-118.

- ↑ "Activity Report on the ordinary legislative procedure 2014-2019" (PDF). European Parliament. Retrieved 3 May 2024. p. 12.

- ↑ "Trilogue". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ "Joint declaration on practical arrangements for the codecision procedure (article 251 of the EC Treaty)". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ "What are trilogues?". European Crypto Initiative. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ "PRESS RELEASE No 35/18" (PDF). General Court of the European Union. Retrieved 3 May 2024.