History

Priestley began writing the Institutes in the 1760s, when he was a student at Daventry, one of the dissenting academies. While there, he had imbibed the pedagogical principles of its founder, Philip Doddridge; although he was dead, Doddridge's emphasis on academic rigour and freedom of thought lived on at the school and impressed Priestley. The ideals would always be a part of Priestley's educational programs. However, researching and writing the work eventually convinced Priestley to abandon the Calvinism of his youth and adopt Socinianism.

Priestley did not publish the Institutes until 1772, when he was at Leeds. In an effort to increase and stabilise membership at his church there, he taught three religious education classes, all outlined in his text. He subdivided the young people of the congregation into three categories: young men from 18 to 30 to whom he taught "the elements of natural and revealed religion" (young women may or may not be included in this group), children under 14 to whom he taught "the first elements of religious knowledge by way of a short catechism in the plainest and most familiar language possible"; and "an intermediate class" to whom he taught "knowledge of the Scriptures only". [5]

Unlike the later Sunday schools established by Robert Raikes, Priestley aimed his classes at middle-class Rational Dissenters; he wanted to teach them "the principles of natural religion and the evidences and doctrine of revelation in a regular and systematic course", something that their parents could not provide. [6]

Priestley wrote texts for the courses that he envisioned: A Catechism for Children and Young Persons (1767) went through eleven English-language editions [7] and A Scripture Catechism, consisting of a Series of Questions, with References to the Scriptures instead of Answers (1772), which went through six British editions by 1817. [8] He aimed to write non-sectarian Catechisms but failed. He offended many orthodox readers by focusing on God's benevolence instead of on Adam's sin and Christ's atonement. Priestley implemented this same system of religious instruction over a decade later in Birmingham, when he became a minister at New Meeting. [9]

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 in Birmingham. At first called the Lunar Circle, "Lunar Society" became the formal name by 1775. The name arose because the society would meet during the full moon, as the extra light made the journey home easier and safer in the absence of street lighting. The members cheerfully referred to themselves as "lunaticks", a contemporary spelling of lunatics. Venues included Erasmus Darwin's home in Lichfield, Matthew Boulton's home, Soho House, Bowbridge House in Derbyshire, and Great Barr Hall.

Joseph Priestley was an English chemist, Unitarian, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator and classical liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted experiments in several areas of science.

Socinianism is a Nontrinitarian Christian belief system developed and co-founded during the Protestant Reformation by the Italian Renaissance humanists and theologians Lelio Sozzini and Fausto Sozzini, uncle and nephew, respectively.

Biblical unitarianism is a Unitarian Christian tradition whose adherents affirm the Bible as their sole authority, and from it base their beliefs that God the Father is one singular being, and that Jesus Christ is God's son but not divine. The term "biblical Unitarianism" is connected first with Robert Spears and Samuel Sharpe of the Christian Life magazine in the 1880s. It is a neologism that gained increasing currency in nontrinitarian literature during the 20th century as the Unitarian churches moved away from mainstream church traditions and, in some instances in the United States, towards merger with Universalism. It has been used since the late 19th century by conservative Christian Unitarians, and sometimes by historians, to refer to scripture-fundamentalist Unitarians of the 16th–18th centuries.

The Joseph Priestley House was the American home of eighteenth-century British theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, educator, and political theorist Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) from 1798 until his death. Located in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, the house, which was designed by Priestley's wife Mary, is Georgian with Federalist accents. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) operated it as a museum dedicated to Joseph Priestley from 1970 to August 2009, when it closed due to low visitation and budget cuts. The house reopened in October 2009, still owned by the PHMC but operated by the Friends of Joseph Priestley House (FJPH).

Joseph Priestley was a British natural philosopher, Dissenting clergyman, political theorist, and theologian. While his achievements in all of these areas are renowned, he was also dedicated to improving education in Britain; he did this on an individual level and through his support of the Dissenting academies. His grammar textbook was innovative and highly influential. More importantly, though, Priestley introduced a liberal arts curriculum at Warrington Academy, arguing that a practical education would be more useful to students than a classical one. He was also the first to advocate the study and teaching of modern history, an interest driven by his belief that humanity was improving and could bring about Christ's Millennium.

Joseph Priestley was a British natural philosopher, political theorist, clergyman, theologian, and educator. He was one of the most influential Dissenters of the late 18th-century.

In 1765, 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley published A Chart of Biography and its accompanying prose description as a supplement to his Lectures on History and General Policy. Priestley believed that the chart and A New Chart of History (1769) would allow students to "trace out distinctly the dependence of events to distribute them into such periods and divisions as shall lay the whole claim of past transactions in a just and orderly manner."

Essay on the First Principles of Government (1768) is an early work of modern liberal political theory by 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley.

The Theological Repository was a periodical founded and edited from 1769 to 1771 by the eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley. Although ostensibly committed to the open and rational inquiry of theological questions, the journal became a mouthpiece for Dissenting, particularly Unitarian and Arian, doctrines.

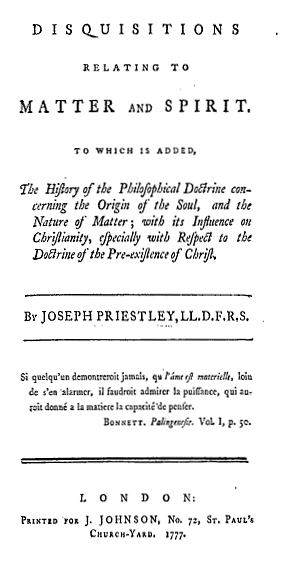

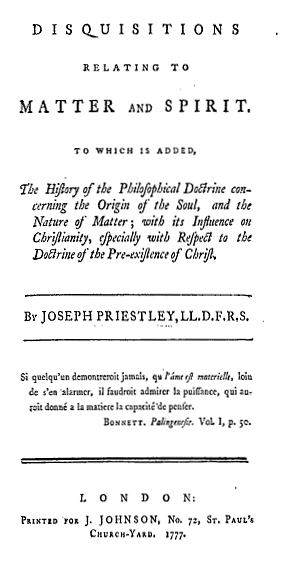

Disquisitions relating to Matter and Spirit (1777) is a major work of metaphysics written by eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley and published by Joseph Johnson.

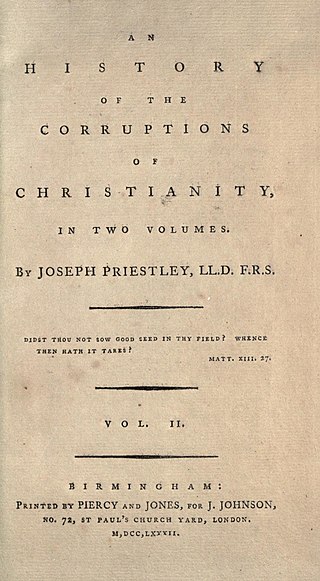

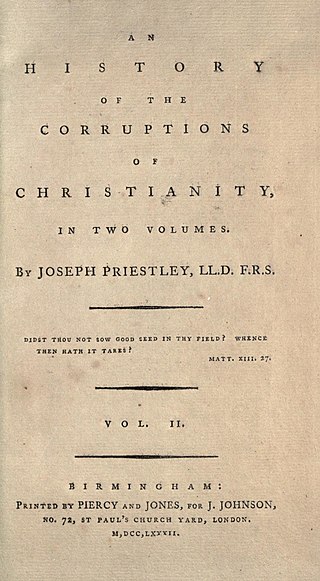

An History of the Corruptions of Christianity, published by Joseph Johnson in 1782, was the fourth part of 18th-century Dissenting minister Joseph Priestley's Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion (1772–74).

The History and Present State of Electricity (1767), by eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley, is a survey of the study of electricity up until 1766, as well as a description of experiments by Priestley himself.

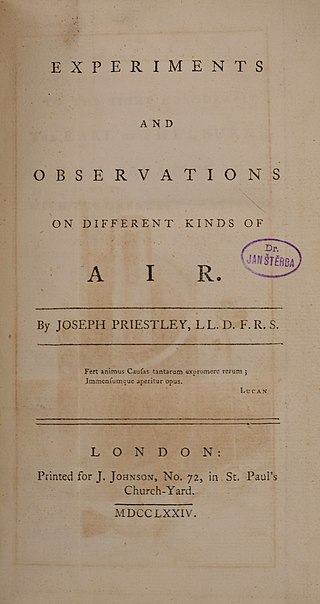

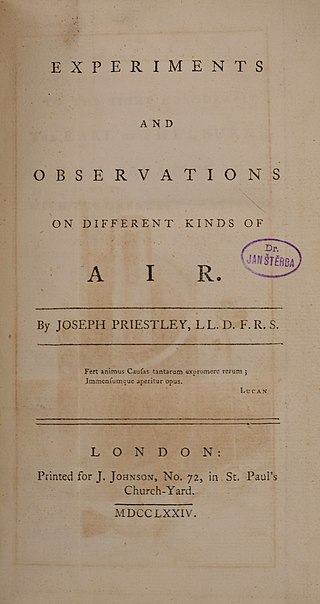

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (1774–86) is a six-volume work published by 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley which reports a series of his experiments on "airs" or gases, most notably his discovery of the oxygen gas.

John Simpson (1746–1812) was an English Unitarian minister and religious writer, known as a biblical critic. Some of his essays were very well known in the nineteenth century. Simpson was also known for his rejection of the literal existence of the devil, following on from writers like Arthur Ashley Sykes.

William Ashdowne (1723–1810) was an English Unitarian preacher.

Daventry Academy was a dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by English Dissenters. It moved to many locations, but was most associated with Daventry, where its most famous pupil was Joseph Priestley. It had a high reputation, and in time it was amalgamated into New College London.

Samuel Bourn the Younger was an English dissenting minister. He was an English presbyterian preaching on protestant values learned from the New Testament. Through his published sermons, he entered the theological debate that flourished around the Arian controversy, and the doctrinal question as to Man's essential nature. He contested the Deism of the Norwich rationalists in the early enlightenment, and challenged the Trinitarian conventional wisdoms about the seat of humanity and its origins.

Summa Universae Theologiae Christianae secundum Unitarios is a statement of faith of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania officially recognised by Joseph II in 1782.