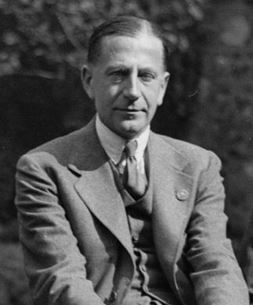

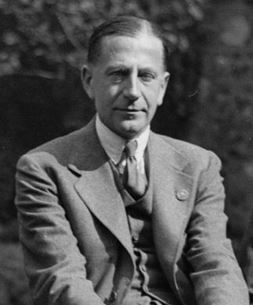

Eoin O'Duffy was an Irish revolutionary, soldier, police commissioner and politician. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a prominent figure in the Ulster IRA during the Irish War of Independence. In this capacity, he became Chief of Staff of the IRA in 1922. He accepted the Anglo-Irish Treaty and as a general became Chief of Staff of the National Army in the Irish Civil War, on the pro-Treaty side.

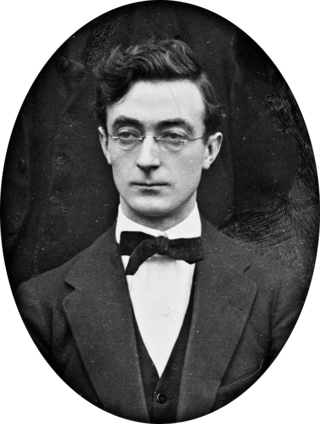

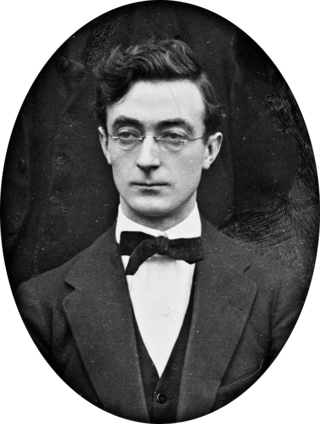

Kevin Christopher O'Higgins was an Irish politician who served as Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice from 1922 to 1927, Minister for External Affairs from June 1927 to July 1927 and Minister for Economic Affairs from January 1922 to September 1922. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1918 to 1927.

The Army Comrades Association (ACA), later the National Guard, then Young Ireland and finally League of Youth, but best known by the nickname the Blueshirts, was a paramilitary organisation in the Irish Free State, founded as the Army Comrades Association in Dublin on 9 February 1932. The group provided physical protection for political groups such as Cumann na nGaedheal from intimidation and attacks by the IRA. Some former members went on to fight for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War after the group had been dissolved.

The relations between the Catholic Church and the state have been constantly evolving with various forms of government, some of them controversial in retrospect. In its history, the Church has had to deal with various concepts and systems of governance, from the Roman Empire to the medieval divine right of kings, from nineteenth- and twentieth-century concepts of democracy and pluralism to the appearance of left-wing and right-wing dictatorial regimes. The Second Vatican Council's decree Dignitatis humanae stated that religious freedom is a civil right that should be recognized in constitutional law.

The National Centre Party, initially known as the National Farmers and Ratepayers League, was a short-lived political party in the Irish Free State. It was founded on 15 September 1932 in the Mansion House, Dublin, with the support of several sitting TDs, including the three Farmers' Party members and thirteen Independents, all of whom feared for their political future if they did not coordinate in a common organisation. Prominent among the latter were party leader Frank MacDermot, a TD for Roscommon since the general election of February 1932, and James Dillon, a TD for Donegal, who was the son of John Dillon, the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

Events from the year 1942 in Ireland.

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) of 1922–1969 was a sub-group of the original pre-1922 Irish Republican Army, characterised by its opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It existed in various forms until 1969, when the IRA split again into the Provisional IRA and Official IRA.

The Irish Brigade fought on the Nationalist side of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. The unit was formed wholly of Roman Catholics by the politician Eoin O'Duffy, who had previously organised the banned quasi-fascist Blueshirts and openly fascist Greenshirts in Ireland. Despite the declaration by the Irish government that participation in the war was unwelcome and ill-advised, 700 of O'Duffy's followers went to Spain. They saw their primary role in Spain as fighting for the Roman Catholic Church against the Red Terror of Spanish anticlericalists. They also saw many religious and historical parallels in the two nations, and hoped to prevent communism gaining ground in Spain.

Córas na Poblachta was a minor Irish republican political party founded in 1940.

The National Corporate Party was a fascist political party in Ireland founded by Eoin O'Duffy in June 1935 at a meeting of 500. It split from Fine Gael when O'Duffy was removed as leader of that party, which had been founded by the merger of O'Duffy's Blueshirts, formally known as the National Guard or Army Comrades Association, with Cumann na nGaedheal, and the National Centre Party. Its deputy leader was Colonel P.J. Coughlan of Cork. Its secretary was Captain Liam D. Walsh of Dublin.

Sinn Féin is the name of an Irish political party founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith. It became a focus for various forms of Irish nationalism, especially Irish republicanism. After the Easter Rising in 1916, it grew in membership, with a reorganisation at its Ard Fheis in 1917. It split in 1922 in response to the Anglo-Irish Treaty which led to the Irish Civil War and saw the origins of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the two parties which have since dominated Irish politics. Another split in the remaining Sinn Féin organisation in the early years of the Troubles in 1970 led to the Sinn Féin of today, which is a republican, left-wing nationalist and secular party.

Peadar O'Donnell was one of the foremost radicals of 20th-century Ireland. O'Donnell became prominent as an Irish republican, socialist politician and writer.

The National League was a political party in Ireland. It was founded in 1926 by William Redmond and Thomas O'Donnell in support of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, a close relationship with the United Kingdom, continued membership of the British Commonwealth and conservative fiscal policy.

The Spanish Civil War lasted from July 17, 1936 to April 1, 1939. While both sides in the Spanish Civil War attracted participants from Ireland, the majority sided with the Nationalist faction.

Irish Socialist volunteers in the Spanish Civil War describes a grouping of IRA members and Irish Socialists who fought in support of the cause of the Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War. These volunteers were taken from both Irish Republican and Unionist political backgrounds but were bonded through a Socialist and anti-clerical political philosophy. Many of the Irish Socialist volunteers who went to Spain later became known as the Connolly Column.

Patrick Belton was an Irish nationalist, politician, farmer, and businessman. Closely associated with Michael Collins, he was active in the 1916 Easter Rising and in the Republican movement in the years that followed. Belton later provided a strong Catholic voice in an Irish nationalist context throughout his career. He was strongly anti-communist and he was a founder and leader of the Irish Christian Front. Supportive of Francisco Franco, Belton however opposed Eoin O'Duffy taking an Irish Brigade to Spain, feeling that they would be needed in Ireland to counter domestic "political ills".

Seán McGarry was a 20th-century Irish nationalist and politician. A longtime senior member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), he served as its president from May 1917 until May 1918 when he was one of a number of nationalist leaders arrested for his alleged involvement in the so-called German Plot.

The Spanish Civil War was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republicans and the Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the left-leaning Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic. The opposing Nationalists were an alliance of Falangists, monarchists, conservatives, and traditionalists led by a military junta among whom General Francisco Franco quickly achieved a preponderant role. Due to the international political climate at the time, the war was variously viewed as class struggle, a religious struggle, a struggle between dictatorship and republican democracy, between revolution and counterrevolution, and between fascism and communism. The Nationalists won the war, which ended in early 1939, and ruled Spain until Franco's death in November 1975.

Aileen von Vittinghof gennant Schell zu Schellenburg, was an American writer, journalist, and political activist. She was a devout Catholic and anti-communist. She is known for her 1938 lecture tour of the United States, where she advocated on behalf of the Nationalist faction of the Spanish Civil War.

Tommy or Thomas Wood was a young Irish man who joined the International Brigades, fighting on the side of the Spanish Republic during the civil war against General Franco's Nationalists. Wood came from a Dublin family which had a strong tradition of Irish Republicanism, and he had lost two uncles in the Irish War of Independence.