Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following 1883 for the financier and politician Herbert Leon in the Victorian Gothic, Tudor and Dutch Baroque styles, on the site of older buildings of the same name.

Cryptanalysis refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic security systems and gain access to the contents of encrypted messages, even if the cryptographic key is unknown.

Ultra was the designation adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. Ultra eventually became the standard designation among the western Allies for all such intelligence. The name arose because the intelligence obtained was considered more important than that designated by the highest British security classification then used and so was regarded as being Ultra Secret. Several other cryptonyms had been used for such intelligence.

In the history of cryptography, the "System 97 Typewriter for European Characters" or "Type B Cipher Machine", codenamed Purple by the United States, was an encryption machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office from February 1939 to the end of World War II. The machine was an electromechanical device that used stepping-switches to encrypt the most sensitive diplomatic traffic. All messages were written in the 26-letter English alphabet, which was commonly used for telegraphy. Any Japanese text had to be transliterated or coded. The 26-letters were separated using a plug board into two groups, of six and twenty letters respectively. The letters in the sixes group were scrambled using a 6 × 25 substitution table, while letters in the twenties group were more thoroughly scrambled using three successive 20 × 25 substitution tables.

William Frederick Friedman was a US Army cryptographer who ran the research division of the Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) in the 1930s, and parts of its follow-on services into the 1950s. In 1940, subordinates of his led by Frank Rowlett broke Japan's PURPLE cipher, thus disclosing Japanese diplomatic secrets before America's entrance into World War II.

Arlington Hall is a historic building in Arlington, Virginia, originally a girls' school and later the headquarters of the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) cryptography effort during World War II. The site presently houses the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center, and the Army National Guard's Herbert R. Temple Jr. Readiness Center. It is located on Arlington Boulevard between S. Glebe Road and S. George Mason Drive.

The vulnerability of Japanese naval codes and ciphers was crucial to the conduct of World War II, and had an important influence on foreign relations between Japan and the west in the years leading up to the war as well. Every Japanese code was eventually broken, and the intelligence gathered made possible such operations as the victorious American ambush of the Japanese Navy at Midway in 1942 and the shooting down of Japanese admiral Isoroku Yamamoto a year later in Operation Vengeance.

Abraham Sinkov was a US cryptanalyst. An early employee of the U.S. Army's Signal Intelligence Service, he held several leadership positions during World War II, transitioning to the new National Security Agency after the war, where he became a deputy director. After retiring in 1962, he taught mathematics at Arizona State University.

The bombe was an electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The US Navy and US Army later produced their own machines to the same functional specification, albeit engineered differently both from each other and from Polish and British bombes.

Cryptanalysis of the Enigma ciphering system enabled the western Allies in World War II to read substantial amounts of Morse-coded radio communications of the Axis powers that had been enciphered using Enigma machines. This yielded military intelligence which, along with that from other decrypted Axis radio and teleprinter transmissions, was given the codename Ultra.

Cryptography was used extensively during World War II because of the importance of radio communication and the ease of radio interception. The nations involved fielded a plethora of code and cipher systems, many of the latter using rotor machines. As a result, the theoretical and practical aspects of cryptanalysis, or codebreaking, were much advanced.

The "Winds Code" is a confused military intelligence episode relating to the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, especially the advance-knowledge debate claiming that the attack was expected.

OP-20-G or "Office of Chief Of Naval Operations (OPNAV), 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section / Communications Security", was the U.S. Navy's signals intelligence and cryptanalysis group during World War II. Its mission was to intercept, decrypt, and analyze naval communications from Japanese, German, and Italian navies. In addition OP-20-G also copied diplomatic messages of many foreign governments. The majority of the section's effort was directed towards Japan and included breaking the early Japanese "Blue" book fleet code. This was made possible by intercept and High Frequency Direction Finder (HFDF) sites in the Pacific, Atlantic, and continental U.S., as well as a Japanese telegraphic code school for radio operators in Washington, D.C.

The Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) was the United States Army codebreaking division through World War II. It was founded in 1930 to compile codes for the Army. It was renamed the Signal Security Agency in 1943, and in September 1945, became the Army Security Agency. For most of the war it was headquartered at Arlington Hall, on Arlington Boulevard in Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington (D.C.). During World War II, it became known as the Army Security Agency, and its resources were reassigned to the newly established National Security Agency (NSA).

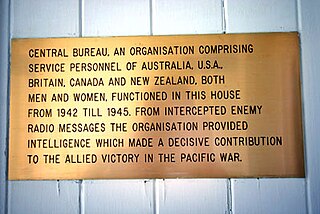

The Central Bureau was one of two Allied signals intelligence (SIGINT) organisations in the South West Pacific area (SWPA) during World War II. Central Bureau was attached to the headquarters of the Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur. The role of the Bureau was to research and decrypt intercepted Imperial Japanese Army traffic and work in close co-operation with other SIGINT centers in the United States, United Kingdom and India. Air activities included both army and navy air forces, as there was no independent Japanese air force.

Before the development of radar and other electronics techniques, signals intelligence (SIGINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) were essentially synonymous. Sir Francis Walsingham ran a postal interception bureau with some cryptanalytic capability during the reign of Elizabeth I, but the technology was only slightly less advanced than men with shotguns, during World War I, who jammed pigeon post communications and intercepted the messages carried.

Hut 7 was a wartime section of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park tasked with the solution of Japanese naval codes such as JN4, JN11, JN40, and JN-25. The hut was headed by Hugh Foss who reported to Frank Birch, the head of Bletchley's Naval section.

The Wireless Experimental Centre (WEC) was one of two overseas outposts of Station X, Bletchley Park, the British signals analysis centre during World War II. The other outpost was the Far East Combined Bureau. Codebreakers Wilfred Noyce and Maurice Allen broke the Japanese Army's Water Transport Code here in 1943, the first high-level Japanese Army code broken. John Tiltman broke prewar Russian and Japanese codes at Simla and Abbottabad.

The 1943 BRUSA Agreement was an agreement between the British and US governments to facilitate co-operation between the US War Department and the British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS). It followed the 1942 Holden Agreement.

The Far East Combined Bureau, an outstation of the British Government Code and Cypher School, was set up in Hong Kong in March 1935, to monitor Japanese, and also Chinese and Russian (Soviet) intelligence and radio traffic. Later it moved to Singapore, Colombo (Ceylon), Kilindini (Kenya), then returned to Colombo.