Related Research Articles

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist denomination based in the United States. It adheres to Wesleyan–Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. It cooperates with other Methodist bodies through the World Methodist Council and Wesleyan Holiness Connection.

The National Baptist Convention of America International, Inc., more commonly known as the National Baptist Convention of America or sometimes the Boyd Convention, is an association of Baptist Christian churches based in the United States. It is a predominantly African American Baptist denomination, and is headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky. The National Baptist Convention of America has members in the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, and Africa. The current president of the National Baptist Convention of America is Dr. Samuel C. Tolbert Jr. of Lake Charles, Louisiana.

The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, or the AME Zion Church (AMEZ) is a historically African-American Christian denomination based in the United States. It was officially formed in 1821 in New York City, but operated for a number of years before then. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology.

Black churches primarily arose in the 19th century, during a time when race-based slavery and racial segregation were both commonly practiced in the United States. Blacks generally searched for an area where they could independently express their faith, find leadership, and escape from inferior treatment in White dominated churches. The Black Church is the faith and body of Christian denominations and congregations in the United States that predominantly minister to, and are also led by African Americans, as well as these churches' collective traditions and members.

Simmons College of Kentucky, formerly known as Kentucky Normal Theological Institute, State University at Louisville, and later as Simmons Bible College, is a private, historically black college in Louisville, Kentucky. Founded in 1879, it is the nation's 107th HBCU and is accredited by the Association for Biblical Higher Education.

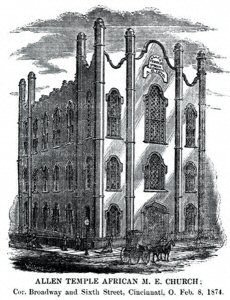

The Allen Temple AME Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, US, is the mother church of the Third Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Founded in 1824, it is the oldest operating black church in Cincinnati and the largest church of the Third Episcopal District of the AME Church.

Religion of Black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of Black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life". Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among Black people in the Thirteen Colonies. The Methodist and Baptist churches became much more active in the 1780s. Their growth was quite rapid for the next 150 years, until their membership included the majority of Black Americans.

Samuel M. Plato (1882–1957) was an American architect and building contractor in the United States. His work includes federal housing projects and U.S. post offices, as well as private homes, banks, churches, and schools. During World War II, the Alabama native was one of the few African-American contractors in the country to be awarded wartime building contracts, which included Wake and Midway Halls. He also received contracts to build at least thirty-eight U.S. post offices across the country.

Bishop Alexander Walters was an American clergyman and civil rights leader. Born enslaved in Bardstown, Kentucky, just before the Civil War, he rose to become a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church at the age of 33, then president of the National Afro-American Council, the nation's largest civil rights organization, at the age of 40, serving in that post for most of the next decade.

The Louisville Leader was a weekly newspaper published in Louisville, Kentucky, from 1917 to 1950.

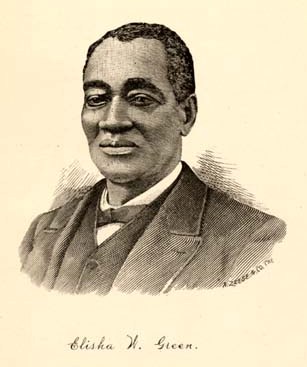

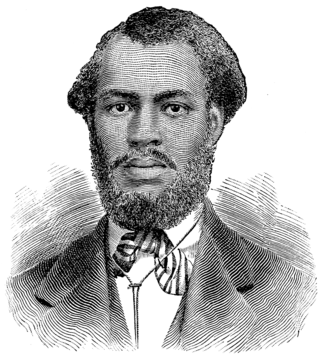

Elisha Winfield Green was a former slave who became a Baptist leader in Kentucky, US. For five years he was moderator of the Consolidated Baptist Educational Association, and he promoted the establishment of what is now the Simmons College of Kentucky. Green suffered from racial intolerance all his life. In 1883, when he was an elderly and respected minister, he was assaulted and beaten for failing to comply with a demand to give up his seat on a train.

The NAACP in Kentucky is very active with branches all over the state, largest being in Louisville and Lexington. The Kentucky State Conference of NAACP continues today to fight against injustices and for the equality of all people.

The following is a timeline of the history of Lexington, Kentucky, United States.

Jeffery Tribble is an ordained elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and a professor of ministry with research interests in Practical Theology, Congregational Studies and Leadership, Ethnography, Evangelism and Church Planting, Black Church Studies, and Urban Church Ministry. Academics and professionals in these fields consider him a renowned thought leader. Tribble's experience in pastoral ministry allows for his work to bridge the gap between academic research and practical church leadership.

Eliza Ann Gardner was an African-American abolitionist, religious leader and women's movement leader from Boston, Massachusetts. She founded the missionary society of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ), was a strong advocate for women's equality within the church, and was a founder of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs.

Marshall W. Taylor was a Methodist Episcopal minister and journalist in Kentucky. He is noted for his book, Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies published in 1882. He was also the first black editor of the Southwestern Christian Advocate, a position he held from 1884 until his death in 1887.

Charles Henry Parrish was a minister and educator in Lexington and Louisville, Kentucky. He was the pastor at Calvary Baptist Church in Louisville from 1886 until his death in 1931. He was a professor and officer at Simmons College, and then served as the president of the Eckstein Institute from 1890 to 1912 and then of Simmons College from 1918 to 1931. His wife, Mary Virginia Cook Parrish and son, Charles H. Parrish Jr., were also noted educators.

Martha Jayne Keys was an American Christian minister. She was the first woman to be ordained in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was president of the West Kentucky conference branch for five years. She was also the author of a 1933 gospel drama, The Comforter.

The Mary E. Bell House is a historic house at 66 Railroad Avenue approximately 1/10th mile south of the Long Island rail road in Center Moriches, Long Island, New York. Built in 1872 by Selah Smith of Huntington who purchased the land, it is significant in the area of ethnic history for the Smith and Bell families and the African-American AME Zion community of Center Moriches during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2020. It is under the Stewardship of the Ketcham Inn Foundation.

References

- ↑ "Go to Church Sunday". The Louisville Leader. Louisville Leader Collection, 1917-1950. University Archives and Records Center, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky. 22 January 1949. p. 3. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ K'Meyer, Tracy E. (2010). Civil Rights in the Gateway to the South: Louisville, Kentucky, 1945-1980. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813139203.

- ↑ Hughlett, Daniel J. (8 October 1949). "The Training of Colored Nurses". The Louisville Leader. Digitally archived by Louisville Leader Collection, 1917-1950, University Archives and Records Center, University of Louisville. Louisville, Kentucky. p. 4. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ↑ Wright, George C. (1992). A History of Blacks in Kentucky, Vol. 2: In Pursuit of Equality, 1890-1980. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0916968235.

- ↑ "Bishop Wallis S. S. Convention Speaker". The Louisville Leader. Digitally archived by Louisville Leader Collection, 1917-1950. University Archives and Records Center, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky. 2 July 1927. p. 1. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "About Us". Hughlett Temple A.M.E. Zion Church. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Wright, George C. (1985). Life Behind A Veil: Blacks In Louisville, Kentucky, 1865-1930. LSU Press. ISBN 0807130567.

- ↑ Wright, George C. (1992). A History of Blacks in Kentucky, Vol. 2: In Pursuit of Equality, 1890-1980. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0916968219.

- ↑ "A.M.E. Zion Religious Leaders Meet". The Louisville Leader . Digitally archived by Louisville Leader Collection, 1917-1950, University Archives and Records Center, University of Louisville. Louisville, Kentucky. 7 March 1942. p. 8. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "To Debate Color Conduct Question". The Louisville Leader . Digitally archived by Louisville Leader Collection, 1917-1950, University Archives and Records Center, University of Louisville. Louisville, Kentucky. 22 January 1949. p. 4. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ McMillen, Sally G. (2001). To Raise Up the South: Sunday Schools in Black and White Churches, 1865-1915. LSU Press. ISBN 0807127493.

- ↑ Carney Smith, Jessie (1996). Notable Black American Women: Book 2 . Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc. ISBN 0810391775.

- ↑ Hill, Kenneth H. (2007). Religious Education in the African American Church: A Comprehensive Introduction. St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press. ISBN 978-0827232846.

- ↑ Collier-Thomas, Bettye (2010). Jesus, Jobs, and Justice: African American Women and Religion. New York: Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0307593054.

- ↑ Walsh, Mary Paula (1999). Feminism and Christian Tradition: An Annotated Bibliography and Critical Introduction to the Literature. Westport, CN: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313371318.