Related Research Articles

Aramaic is a Northwest Semitic language that originated among the Arameans in the ancient region of Syria, and quickly spread to Mesopotamia and eastern Anatolia where it has been continually written and spoken, in different varieties, for over three thousand years. Aramaic served as a language of public life and administration of ancient kingdoms and empires, and also as a language of divine worship and religious study. Several modern varieties, the Neo-Aramaic languages, are still spoken.

Yeshua or Y'shua was a common alternative form of the name Yehoshua in later books of the Hebrew Bible and among Jews of the Second Temple period. The name corresponds to the Greek spelling Iesous (Ἰησοῦς), from which, through the Latin IESVS/Iesus, comes the English spelling Jesus.

Biblical Aramaic is the form of Aramaic that is used in the books of Daniel and Ezra in the Hebrew Bible. It should not be confused with the Targums – Aramaic paraphrases, explanations and expansions of the Hebrew scriptures.

There exists a consensus among scholars that the language of Jesus and his disciples was Aramaic. Aramaic was the common language of Judea in the first century AD. The villages of Nazareth and Capernaum in Galilee, where Jesus spent most of his time, were Aramaic-speaking communities. Jesus likely spoke a Galilean variant of the language, distinguishable from that of Jerusalem. It is also likely that Jesus knew enough Koine Greek to converse with those not native to Judea, and it is reasonable to assume that Jesus was well versed in Hebrew for religious purposes.

The Jewish War or Judean War, also referred to in English as The Wars of the Jews, is a book written by Josephus, a first-century Roman-Jewish historian. It has been described by Steve Mason as "perhaps the most influential non-biblical text of Western history".

David Flusser was an Israeli professor of Early Christianity and Judaism of the Second Temple Period at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

David N. Bivin is an Israeli-American biblical scholar, member of the Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research. His role at the Jerusalem School involves publishing the journal Jerusalem Perspective and organizing seminars.

The Jewish–Christian Gospels were gospels of a Jewish Christian character quoted by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Eusebius, Epiphanius, Jerome and probably Didymus the Blind. All five call the gospel they know the "Gospel of the Hebrews". But most modern scholars have concluded that the five early church historians are not quoting the same work. As none of the works survive to this day attempts have been made to reconstruct them from the references in the Church Fathers. The majority of scholars believe that there existed one gospel in Aramaic/Hebrew and at least two in Greek, although a minority argue that there were only two, in Aramaic/Hebrew and in Greek.

Robert Lisle Lindsey (1917–1995), founded together with David Flusser the Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research.

Bradford Humes Young, also known as Brad Young, is a professor of Biblical Literature in Judeo Christian Studies at the Graduate Department of Oral Roberts University (ORU). He is also founder and president of the Gospel Research Foundation, Inc.

Philip Maurice Casey was a British scholar of New Testament and early Christianity. He was an emeritus professor at the University of Nottingham, having served there as Professor of New Testament Languages and Literature at the Department of Theology.

The Jerusalem School Hypothesis is one of many possible solutions to the synoptic problem, that the Gospel of Luke and the Gospel of Matthew both relied on older texts which are now lost. It was developed by Robert Lindsey, from the Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research.

In textual criticism of the New Testament, the L source is a hypothetical oral or textual tradition which the author of Luke–Acts may have used when composing the Gospel of Luke.

In the New Testament, Jesus is referred to as the King of the Jews, both at the beginning of his life and at the end. In the Koine Greek of the New Testament, e.g., in John 19:3, this is written as Basileus ton Ioudaion.

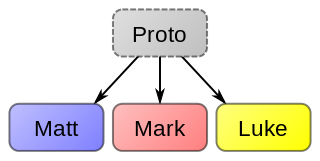

The Hebrew Gospel hypothesis is that a lost gospel, written in Hebrew or Aramaic, predated the four canonical gospels. Some have suggested a complete unknown proto-gospel as the source of the canonical gospels. This hypothesis is usually based upon an early Christian tradition from the 2nd-century bishop Papias of Hierapolis. According to Papias, Matthew the Apostle was the first to compose a gospel, and he did so in Hebrew. Papias appeared to imply that this Hebrew or Aramaic gospel was subsequently translated into the canonical Gospel of Matthew. Jerome took this information one step further and claimed that all known Jewish-Christian gospels really were one and the same, and that this gospel was the authentic Matthew. As a consequence he assigned all known quotations from Jewish-Christian gospels to the "gospels of the Hebrews", but modern studies have shown this to be untenable. Modern variants of the hypothesis survive, but have not found favor with scholars as a whole.

The New Testament was written in a form of Koine Greek, which was the common language of the Eastern Mediterranean from the conquests of Alexander the Great until the evolution of Byzantine Greek.

Geoffrey Allan Khan FBA is a British linguist who has held the post of Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Cambridge since 2012. He has published grammars for the Aramaic dialects of Barwari, Qaraqosh, Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Halabja in Iraq; of Urmia and Sanandaj in Iran; and leads the North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic DatabaseArchived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

"Finger of God" is a phrase used in the Torah, translated into the Christian Bible. In Exodus 8:16–20 it is used during the plagues of Egypt by the Egyptian magicians. In Exodus 31:18 and Deuteronomy 9:10 it refers to the method by which the Ten Commandments were written on tablets of stone that were brought down from Mount Sinai by Moses.

Aramaic studies are scientific studies of the Aramaic languages and cultural history of Arameans. As a specific field within Semitic studies, Aramaic studies are closely related to similar disciplines, like Hebraic studies and Arabic studies.

The criterion of contextual credibility, also variously called the criterion of Semitisms and Palestinian background or the criterion of Semitic language phenomena and Palestinian environment, is a tool used by Biblical scholars to help determine whether certain actions or sayings by Jesus in the New Testament are from the Historical Jesus. Simply put, if a tradition about Jesus does not fit the linguistic, cultural, historical and social environment of Jewish Aramaic-speaking 1st-century Palestine, it is probably not authentic. The linguistic and the environmental criteria are treated separately by some scholars, but taken together by others.

References

- ↑ Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research. Retrieved 05 Nov. 2006

- ↑ "A Tribute to Robert L. Lindsey, Ph. D. (1917-1995) and his work...:Excerpt from November 1996 Tree of Life Quarterly Membership Magazine", HaY'Did. Retrieved 05 Nov. 2006. Archived 2006-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Methodology." Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research. Retrieved 26 Sep. 2009. Archived 2015-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ As early as the beginning of the 20th century, we already have: Moses Hirsch Segal Mishnaic Hebrew and Its Relation to Biblical Hebrew and to Aramaic. A Grammatical Study ... Reprinted from the Jewish Quarterly Review for July Horace Hart: Oxford, 1909.

- ↑ Meier "rejects a major academic failure of Jesus research: mouthing respect for Jesus' Jewishness while avoiding like the plague the beating heart of that Jewishness: the Torah in all its complexity. However bewildering the positions Jesus sometimes takes, he emerges from this volume as a Palestinian Jew engaged in the legal discussions and debates proper to his time and place. It is Torah and Torah alone that puts flesh and bones on the spectral figure of "Jesus the Jew." No halakic Jesus, no historical Jesus. This is the reason why many American books on the historical Jesus may be dismissed out of hand: their presentation of lst-century Judaism and especially of Jewish Law is either missing in action or so hopelessly skewed that it renders any portrait of Jesus the Jew distorted from the start. It is odd that it has taken American scholarship so long to absorb this basic insight: either one takes Jewish Law seriously and "gets it right" or one should abandon the quest for the historical Jesus entirely.....The patient reader of Volume Four of A Marginal Jew may at this juncture be sick unto death of the mantra, 'the historical Jesus is the halakic Jesus.' But at least such readers have been inoculated for life against the virus that induces legal amnesia in most Americans writing on Jesus. The halakic dimension of the historical Jesus is never exciting but always essential." John P. Meier, "Conclusion to Volume Four" in A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume IV: Law and Love, (The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library: Yale University Press, 2009), 648 and 649.

- ↑ Among others: Delbert Royce Burkett, Rethinking the Gospel sources: from proto-Mark to Mark, T&T Clark: NY, 4. Beate Ego, Armin Lange, Peter Pilhofer, Gemeinde ohne Tempel /Community without Temple, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, Mohr Siebeck: Tubingen, 462n2

- ↑ http://www.jerusalemschool.org/Methodology/index.htm [ dead link ]

- ↑ James R. Edwards, The Hebrew Gospel and the Development of the Synoptic Tradition. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009.

- ↑ Randall Buth and Brian Kvasnica. "Temple Authorities and Tithe-Evasion: The Linguistic Background and Impact of the Parable of the Vineyard Tenants and the Son." Pages 53-80 (essay), 259-317 (Critical Notes) in Jesus' Last Week: Jerusalem Studies on the Synoptic Gospels, Volume 1. Edited by R. S. Notley, B. Becker, and M. Turnage. Jewish and Christian Perspectives 11. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- ↑ For a collected bibliography on David Flusser see Malcolm Lowe, "Bibliography of the Writings of David Flusser." Immanuel Archived 2010-06-28 at the Wayback Machine 24/25 (1990): 292-305. For collected bibliography on Robert L. Lindsey see David Bivin, "The Writings of Robert L. Linsdey" on www.jerusalemperspective.com. The list of members' publications is extensive. Here are a just a few recent representative works: --- Randall Buth, "A Hebraic approach to Luke and the resurrection accounts: still needing to re-do Dalman and Moulton." Pages 293-316 in Grammatica intellectio Scripturae; saggi filologici di Greco biblico in onore di Lino Cignelli OFM. A cura di Rosario Pierri. Edited by Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 2006. --- Weston W. Fields. The Dead Sea Scrolls, A Full History, Vol. 1 (600 pp., with photos), (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009). --- Yair Furstenberg, "Defilement penetrating the body: a new understanding of contamination in Mark 7.15." New Testament Studies 54, no. 2 (2008): 176-200. --- Brian Kvasnica, "Shifts in Israelite War Ethics and Early Jewish Historiography of Plundering." Pages 175-96 in Writing and Reading War Rhetoric, Gender, and Ethics in Biblical and Modern Contexts.Edited by Brad E. Kelle and Frank R. Ames. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008. --- Daniel A. Machiela, The Dead Sea Genesis Apocryphon: A New Text and Translation with Introduction and Special Treatment of Columns 13-17, Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah, 79. Leiden: Brill, 2009. --- R. Steven Notley, "The Sea of Galilee: Development of an Early Christian Toponym." Journal of Biblical Literature 128, no. 2 (2009): 183-88. --- R. Steven Notley, "Jesus' Jewish Hermeneutical Method in the Nazareth Synagogue." Pages 46-59 in Early Christian Literature and Intertextuality; Volume 2: Exegetical Studies. Edited by C. A. Evans and H. D. Zacharias. London: T&T Clark, 2009. --- Serge Ruzer, "Son of God as Son of David: Luke's attempt to biblicize a problematic notion." Pages 321-52 in Babel und Bibel 3. Annual of ancient Near Eastern, Old Testament, and Semitic studies. Edited by Kogan Leonid. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006. --- Serge Ruzer, Mapping the New Testament: Early Christian Writings as a Witness for Jewish Biblical Exegesis, Jewish and Christian Perspectives Series, 13. Leiden: Brill, 2007. --- Serge Ruzer, "The Historical Jesus in Recent Israeli Research." Pages 315-41 in Le Jésus historique à travers le monde = The historical Jesus around the world. Ed. by C. Boyer and G. Rochais. Héritage et projet; 75. Montréal: Fides, 2009. --- Brian Schultz, "Jesus as Archelaus in the Parable of the Pounds (Lk. 19:11-27)." Novum Testamentum 49 (2007): 105-27. --- Brad H. Young, Meet the Rabbis: Rabbinic Thought and the Teachings of Jesus. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007.

- ↑ Jesus' Last Week, edited by R. Steven Notley, Marc Turnage, and Brian Becker. Vol 1. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- ↑ Accessed from https://www.eisenbrauns.com/ECOM/_32H00EUWH.HTM%5B%5D: Table of Contents: David Flusser, "The Synagogue and the Church in the Synoptic Gospels" 17-40 • Shmuel Safrai, "Literary Languages in the Time of Jesus" 41-52 • Randall Buth and Brian Kvasnica, "Temple Authorities and Tithe-Evasion: The Parable of the Vineyard, the Tenants and the Son" 53-80 • Serge Ruzer, "The Double Love Precept in the New Testament and the Rule of the Community" 81-106 • Steven Notley "Learn the Lesson of the Fig Tree" 107-120 • Steven Notley, "Eschatological Thinking of the Dead Sea Sect and the Order of the Christian Eucharist" 121-138 • Marc Turnage, "Jesus and Caiaphas: An Intertextual-Literary Evaluation." 139-168 • Chana Safrai, "The Kingdom of God and Study of Torah" 169-190 • Brad Young, "The Cross and the Jewish People" 191- 210 • David Bivin, "Evidence of an Editor's Hand in Two Instances of Mark's Account of Jesus' Last Week" 211-224 • Shmuel Safrai, "Early Testimonies in the New Testament Laws and Practices Relating to Pilgrimage and Pesah" 225-244 • Hanan Eshel, "Use of the Hebrew Language in Economic Documents from the Judaean Desert" 245-258 • Randall Buth and Brian Kvasnica, "Appendix: Critical Notes on the VTS" (=Temple Authorities and Tithe-Evasion: The Parable of the Vineyard, the Tenants and the Son)259-317.

- ↑ Buth, R. and Notley, R.S. (2014) The language environment of first century Judaea : Jerusalem studies in the Synoptic Gospels. Leiden: Brill. (Jewish and Christian perspectives series, 26)

- ↑ The articles in this collection demonstrate that a change is taking place in New Testament studies. Throughout the twentieth century, New Testament scholarship primarily worked under the assumption that only two languages, Aramaic and Greek, were in common use in the land of Israel in the first century. The current contributors investigate various areas where increasing linguistic data and changing perspectives have moved Hebrew out of a restricted, marginal status within first-century language use and the impact on New Testament studies. Five articles relate to the general sociolinguistic situation in the land of Israel during the first century, while three articles present literary studies that interact with the language background. The final three contributions demonstrate the impact this new understanding has on the reading of Gospel texts. Table of contents Introduction: Language Issues Are Important for Gospel Studies Sociolinguistic Issues In a Trilingual Framework 1. Guido Baltes, “The Origins of the “Exclusive Aramaic Model.” 2. Guido Baltes, “The Use of Hebrew and Aramaic.” 3. Randall Buth and Chad T. Pierce, “Hebraisti” 4. Marc Turnage, “The Linguistic Ethos of Galilee” 5. Serge Ruzer, “Syriac Authors” Literary Issues In a Trilingual Framework 6. Daniel A. Machiela, “Hebrew, Aramaic Translation” 7. Randall Buth, “Distinguishing Hebrew from Aramaic.” 8. R. Steven Notley, “Non-LXXisms” Reading Gospel Texts in a Trilingual Framework 9. R. Steven Notley and Jeffrey P. Garcia “Hebrew-Only Exegesis” 10. David N. Bivin, “Petros, Petra” 11. Randall Buth, “The Riddle” (accessed 04/02/2014 from http://www.brill.com/products/book/language-environment-first-century-judaea)

- ↑ David Bivin and Roy B. Blizzard Jr. Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus, Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image Publishers, 1994.

- ↑ Michael L. Brown "The Issue of the Inspired Text: A Rejoinder to David Bivin" in Mishkan, Isso No. 20, 63.

- ↑ Baltes, Guido. Hebräisches Evangelium und synoptische Überlieferung: Untersuchungen zum hebräischen Hintergrund der Evangelien. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011, 65-67.

- ↑ This book is evidently catered toward the academic community, because of its style, abundance of footnotes and type of publisher. The review by Collins published in Nova Testamentum supports the academic nature.

- ↑ Nina Collins is a British widely published scholar in the fields of Judaism and Christianity.

- ↑ Collins, Nina L. "Review: R. Steven Notley, Marc Turnage, and Brian Becker, eds., Jesus' Last Week: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels - Volume One." NovT 49/4 (2007) 407-409.

- ↑ Robert L. Webb, McMaster University, in Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus, Jan2007, Vol. 5 Issue 1

- ↑ Daniel M. Gurtner, "Review: R. Steven Notley, Marc Turnage, and Brian Becker, eds., Jesus' Last Week: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels - Volume One." Review of Biblical Literature feb (2011).