Zionism is a nationalist movement that emerged in the 19th century to espouse support for the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine, a region roughly corresponding to the Land of Israel in Jewish tradition. Following the establishment of Israel, Zionism became an ideology that supports "the development and protection of the State of Israel".

The Haskalah, often termed as the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Europe and the Muslim world. It arose as a defined ideological worldview during the 1770s, and its last stage ended around 1881, with the rise of Jewish nationalism.

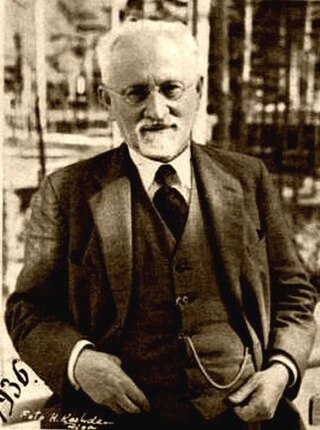

Simon Dubnow was a Jewish-Russian historian, writer and activist.

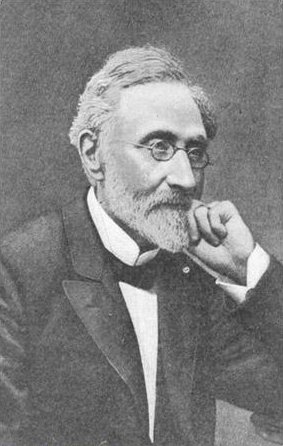

Heinrich Graetz was amongst the first historians to write a comprehensive history of the Jewish people from a Jewish perspective.

Jewish Autonomism, not connected to the contemporary political movement autonomism, was a non-Zionist political movement and ideology that emerged in the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, before spreading throughout all of Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century. In the late 19th century, Jewish Autonomism was seen "together with Zionism [as] the most important political expression of the Jewish people in the modern era." One of its first and major proponents was the historian and activist Simon Dubnow. Jewish Autonomism is often referred to as "Dubnovism" or "folkism".

"Wissenschaft des Judentums" refers to a nineteenth-century movement premised on the critical investigation of Jewish literature and culture, including rabbinic literature, to analyze the origins of Jewish traditions.

Paula Hyman was an American social historian who served as the Lucy Moses Professor of Modern Jewish History at Yale University.

Richard I. Cohen, also known as Richard Yerachmiel Cohen is a professor of history, presently holding the Paulette and Claude Kelman Chair in French Jewry Studies in the Department of Jewish History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He specializes in the history of Jews in Western and Central Europe in the modern period, in particular the Jews of France, art history, Jewish historiography, and The Holocaust.

Jacob Katz was an acclaimed Jewish historian and educator.

Jewish secularism refers to secularism in a Jewish context, denoting the definition of Jewish identity with little or no attention given to its religious aspects. The concept of Jewish secularism first arose in the late 19th century, with its influence peaking during the interwar period.

Ben-Zion Dinur was a Zionist activist, educator, historian and Israeli politician.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi was the Salo Wittmayer Baron Professor of Jewish History, Culture and Society at Columbia University, a position he held from 1980 to 2008.

The Leo Baeck Institute, established in 1955, is an international research institute with centres in New York City, London, Jerusalem and Berlin, that are devoted to the study of the history and culture of German-speaking Jewry. The institute was founded in 1955 by a consortium of influential Jewish scholars including Hannah Arendt, Martin Buber and Gershom Scholem. The Leo Baeck Medal has been awarded since 1978 to those who have helped preserve the spirit of German-speaking Jewry in culture, academia, politics, and philanthropy.

Wir Juden is a 1934 book by German rabbi Joachim Prinz that concerns Hitler's rise to power as a demonstration of the defeat of liberalism and assimilation as a solution for the "Jewish Question", and advocated a Zionist alternative to save German Jews. The book urged German Jews to escape National Socialist persecution by emigrating to Palestine. Prinz himself was expelled in 1937, travelling to the US where he became a leader of the American Jewish community and the Civil Rights Movement.

David N. Myers is a professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he holds the Sady and Ludwig Kahn Chair in Jewish History. Myers was the president and CEO of the Center for Jewish History from July 2017 to August 2018. He serves as the President of the New Israel Fund Board.

Otto Dov Kulka was an Israeli historian, professor emeritus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His primary areas of specialization were the study of modern antisemitism from the early modern age until its manifestation under the National-Socialist regime as the "Final Solution"; Jewish thought in Europe – and Jews in European thought – from the 16th to the 20th century; Jewish-Christian relations in modern Europe; the history of the Jews in Germany; and the study of the Holocaust.

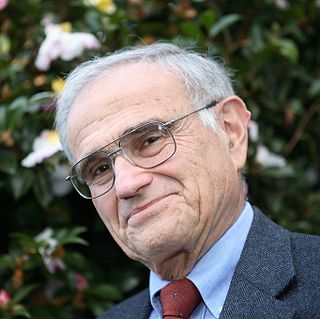

Michael Albert Meyer is a German-born American historian of modern Jewish history. He taught for over 50 years at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, Ohio. He is currently the Adolph S. Ochs Emeritus Professor of Jewish History at that institution. He was one of the founders of the Association for Jewish Studies, and served as its president from 1978–80. He also served as International President of the Leo Baeck Institute from 1992–2013. He has published many books and articles, most notably on the history of German Jews, the origins and history of the Reform movement in Judaism, and Jewish people and faith confronting modernity. He is a three-time National Jewish Book Award winner.

Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory is a non-fiction work of Jewish historiography first published in 1982 by the historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi (1932–2009), a professor of Jewish history at Columbia University. It consists of four lectures that Yerushalmi gave as part of the 1980 series of "Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies", now known as the Samuel and Althea Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies, at the University of Washington in Seattle. Harold Bloom wrote the foreword for the publication. The title, Zakhor, is the Hebrew word for remember. The New Yorker described the book as "one of the most influential works on Jewish history" since the 1950s.

Carl Anton born Moses Gershon Cohen, was a Curonian writer and Hebraist.

Roni Stauber is an Israeli historian. He is an Associate Professor in the Department of Jewish History at Tel Aviv University. Stauber serves as the Director of the Goldstein-Goren Diaspora Research Center and the Director of the university's Diploma Program in Archival and Information Science. Stauber is also a member of the academic committee of Yad Vashem. His research focuses on various aspects of Holocaust memory and the formation of Holocaust consciousness in Israel and around the world. In particular, he examines the interrelations between ideology and politics, and between collective memory and historiography, with a focus on Israeli-German relations.