John D. James, Thomas G. James, and David D. James were brothers and 19th-century American businessmen who worked as interstate slave traders for the 30 years prior to the American Civil War. They also opened a bank in 1855.

John D. James, Thomas G. James, and David D. James were brothers and 19th-century American businessmen who worked as interstate slave traders for the 30 years prior to the American Civil War. They also opened a bank in 1855.

Born in the 1810s in the Nashville, Tennessee area, they grew wealthy as interstate slave traders and bankers before the American Civil War. [1] They had a stand at the Forks of the Road slave market in Natchez, Mississippi where they sold people that had been transported from the Upper South. [2]

In 1835, a formerly enslaved woman named Julia sued her daughter Harriet's owner Samuel T. McKenney, and slave traders William Walker and Thomas D. James on the basis that she had been trafficked illegally through a free state (Illinois) so that she could be resold in Missouri and therefore was entitled to her freedom. [3] [4] In 1848, John D. James sold nine enslaved people to a Joseph J. B. Kirk in Point Coupee Parish, Louisiana. One of those people, Simon, repeatedly tried to escape and was ultimately drowned while on the run. Kirk sued James under Louisiana's slave redhibition laws, which were essentially mandatory warranties. According to historian Ariela J. Gross, James argued in court that Louisiana was endangered slavery itself by the application of these laws. [5]

In 1849 the James' were sued in Mississippi. According to an abstract of the case record for James v. Herring, 12 S. and M. 336, January 1849., David D. James escorted a drove south from Virginia in 1845 that included an enslaved man named Egerton. According to an abstract of the case James v. Herring, they "left Richmond about the 21st of August...and reached Natchez about the 3d or 4th of October following." [6] When Egerton died of an abdominal/gastrointestinal illness shortly after being settled on the plantation of Mary Herring, she sued for the purchase price and damages. [6] In 1855 they were sued in Tennessee. According to case record James v. Drake, 35 Tenn. 340 (Tenn. 1855), the intent of the suit was "to recover the value of a slave named Bill" who had died of smallpox after one of the brothers had sent an enslaved woman named Kitty to Thomas D. James' house, shortly after which she exhibited symptoms of highly contagious smallpox, which ultimately infected and killed Bill. [7] According to historian Gross, allowing disputes about a solitary slave to get to court was a hallmark of "local traders like John D. James and his family members" whereas very large interstate traders usually sought to resolve such disputes with negotiation outside a courtroom. [8]

In 1855, John D. James, David D. James, and A. Wheless opened a bank in Nashville. [9] The bank had $500,000 in capital. [10]

Despite the disdain with which slave traders were purportedly regarded in the South, letters between John D. James and a plantation owner named William Terry demonstrate that the merchant and planter classes socialized. According to Gross, "Although he wrote to Terry about the slaves he had for sale, he also wrote, 'Your Daughter Eliza at our house all yesterday...I was glad to see her look so well; I was at Mr Scotts about a week ago they were all well, Mary requests me to present her love & respects to you.'" [11]

At the time of the 1850 census, John D. James was listed on the slave schedules as the legal owner of 27 people in Davidson County, Tennessee. [12] Thomas G. James was the legal owner of five people. [12]

Thomas G. James caught the attention of Harriet Beecher Stowe and is mentioned in her 1853 non-fiction polemic A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin . [13]

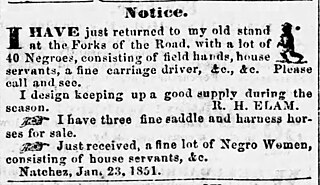

...we take up the Natchez (Mississippi) Courier of Nov. 20th, 1852, and there read:

NEGROES. The undersigned would respectfully state to the public that he has leased the stand in the Forks of the Road, near Natchez, for a term of years, and that he intends to keep a large lot of NEGROES on hand during the year. He will sell as low or lower than any other trader at this place or in New Orleans. He has just arrived from Virginia with a very likely lot of Field Men and Women; also, House Servants, three Cooks, and a Carpenter. Call and see A fine Buggy Horse, a Saddle Horse, and a Carryall, on hand, and for sale. THOS. G. JAMES. Natchez, Sept. 28, 1852.

Where in the world did this lucky Mr. THOS. G. JAMES get this likely Virginia "assortment"? Probably in some county which Mr. Thornton Randolph never visited. Had no families been separated to form the assortment? We hear of a lot of field men and women. Where are their children? We hear of a lot of house-servants—of "three cooks," and "one carpenter," as well as a "fine buggy horse." Had these unfortunate cooks and carpenters no relations? Did no sad natural tears stream down their dark cheeks when they were being "assorted" for the Natchez market? Does no mournful heart among them yearn to the song of 'O, carry me back to old Virginny'? [13]

Later in the book Stowe used a second Thomas James advertisement as part of her evidence for her point that black families in Virginia were being scoured by slave traders to serve the markets of the lower Mississippi. [14]

In 1859, Thomas G. James advertised in a Nashville newspaper, offering "CASH FOR NEGROES" and promised therein that the "undersigned will pay the cash for fifty likely young Negroes; he will also board negroes and sell them on commission at No. 18 Cedar street, Nashville, Tenn., will be responsible for the escape of all negroes left in charge. Call and see." [15]

In 1865 a Tennessee court ruled in the case of John D. James vs. Ocoee Bank, that "an acceptor of a Bill of Exchange, upon its non-payment at maturity, is not entitled to notice; his liability being absolute and unconditional." [16] In 1867 David and Thomas James sued each other, and a tract of land was to be auctioned as a part of the settlement. [17]

All three lost their wealth in the war, and all three lived into their 80s. [1] As of 1891, Thomas G. James lived in penury in Nashville, David D. James lived in Texas, and John D. James lived in California. [1]

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

John Armfield (1797–1871) was an American slave trader. He was the co-founder of Franklin & Armfield, "the largest slave trading firm" in the United States. He was also the developer of Beersheba Springs, Tennessee, and a co-founder of Sewanee: The University of the South.

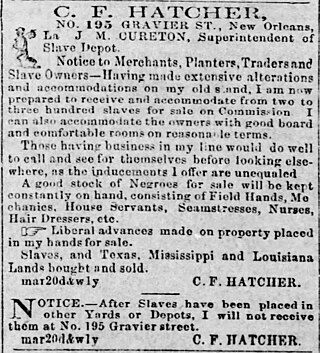

Charles F. Hatcher, typically advertising as C. F. Hatcher, was a 19th-century American slaver dealing out of Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana. He also worked as a trader of financial instruments, specie, and stocks, and as a land agent, with a special interest in selling Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas real estate to speculators and settlers.

The Natchez slave market was a slave market in Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. Slaves were originally sold throughout the area, including along the Natchez Trace that connected the settlement with Nashville, along the Mississippi River at Natchez-Under-the-Hill, and throughout town. From 1833 to 1863, the Forks of the Road slave market was located about a mile from downtown Natchez at the intersection of Liberty Road and Washington Road, which has since been renamed to D'Evereux Drive in one direction and St. Catherine Street in the other. The market differed from many other slave sellers of the day by offering individuals on a first-come first-serve basis rather than selling them at auction, either singly or in lots. At one time the Forks of the Road was the second-largest slave market in the United States, trailing only New Orleans.

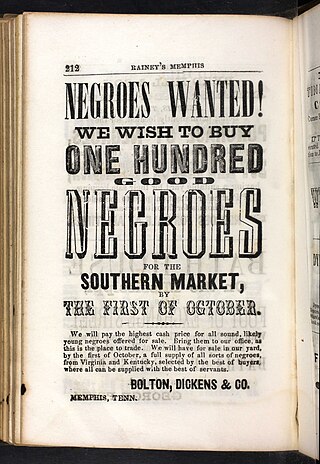

Bolton, Dickens & Co. was a slave-trading business of the antebellum United States, headquartered in Memphis, Tennessee. Several principals of the firm eventually shot and killed one another as part of a long-running dispute over money, events known as the Bolton–Dickens feud. A Bolton & Dickens account ledger survived the American Civil War and is a valuable primary source on the interstate slave trade.

Byrd Hill was a slave trader of Tennessee and Mississippi prior to the American Civil War. Byrd Hill has been described as one of the "big four" slave traders in the centrally located city of Memphis on the Mississippi River. Hill was partners for a time with Nathan Bedford Forrest and is believed to have resold six of the Africans illegally trafficked to the United States on the Wanderer in 1859. Hill also made a fleeting appearance in Harriet Beecher Stowe's A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Fugitive slave advertisements in the United States or runaway slave ads, were paid classified advertisements describing a missing person and usually offering a monetary reward for the recovery of the valuable chattel. Fugitive slave ads were a unique vernacular genre of non-fiction specific to the antebellum United States. These ads often include detailed biographical information about individual enslaved Americans including "physical and distinctive features, literacy level, specialized skills," and "if they might have been headed for another plantation where they had family, or if they took their children with them when they ran."

Theophilus Freeman was a 19th-century American slave trader of Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi. He was known in his own time as wealthy and problematic. Freeman's business practices were described in two antebellum American slave narratives—that of John Brown and that of Solomon Northup—and he appears as a character in both filmed dramatizations of Northup's Twelve Years a Slave.

Simeon G. "Sim" Eddins was a 19th-century farmer and slave trader. He primarily traded in the Middle Tennessee region of the United States, but he also purchased enslaved people in Virginia, and sold people in Alabama. Among the children he bought and sold was nine-year-old Henry McDaniel, who as an adult became the father of Academy Award-winning actress Hattie McDaniel. Sim Eddins was killed in 1861 in a Mississippi River steamboat boiler explosion.

Thomas McCargo, also styled Thos. M'Cargo, was a 19th-century American slave trader who worked in Virginia, Kentucky, Mississippi and Louisiana. He is best remembered today for being one of the slave traders aboard the Creole, which was a coastwise slave ship that was commandeered by the enslaved men aboard and sailed to freedom in the British Caribbean. The takeover of the Creole is considered the most successful slave revolt in antebellum American history.

James McMillin was an American tavern keeper and slave trader of Kentucky. He was implicated in more than one case of attempted kidnapping into slavery. In 1857 Memphis slave trader Isaac Bolton shot McMillin several times over an unprofitable trade. McMillin died hours later in the home of Memphis slave trader Nathan Bedford Forrest. His last name is very often spelled McMillan or McMillen; this article uses the spelling that appears on his grave marker and hometown newspaper.

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Torture of slaves in the United States was fairly common, as part of what many slavers claimed was necessary discipline. As one history put it, "Stinted allowance, imprisonment, and whipping were the usual methods of punishment; incorrigibles were sometimes 'ironed' or sold."

Andrew Jackson bought and sold slaves from 1788 until 1844, both for use as a plantation labor force and for short-term financial gain through slave arbitrage. Jackson was most active in the interregional slave trade, which he euphemistically termed "the mercantile transactions," from the 1790s through the 1810s. Available evidence shows that speculator Jackson trafficked people between his hometown of Nashville, Tennessee, and the slave markets of the lower Mississippi River valley.