Related Research Articles

Edward Jenner, was an English physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms vaccine and vaccination are derived from Variolae vaccinae, the term devised by Jenner to denote cowpox. He used it in 1798 in the title of his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae known as the Cow Pox, in which he described the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox.

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating the body's adaptive immunity, they help prevent sickness from an infectious disease. When a sufficiently large percentage of a population has been vaccinated, herd immunity results. Herd immunity protects those who may be immunocompromised and cannot get a vaccine because even a weakened version would harm them. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases; widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the elimination of diseases such as polio and tetanus from much of the world. However, some diseases, such as measles outbreaks in America, have seen rising cases due to relatively low vaccination rates in the 2010s – attributed, in part, to vaccine hesitancy. According to the World Health Organization, vaccination prevents 3.5–5 million deaths per year.

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by the cowpox virus (CPXV). It presents with large blisters in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, though in the last several decades more often from infected cats. The hands and face are most frequently affected and the spots are generally very painful.

The smallpox vaccine is the first vaccine to have been developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox virus. Cowpox served as a natural vaccine until the modern smallpox vaccine emerged in the 20th century. From 1958 to 1977, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a global vaccination campaign that eradicated smallpox, making it the only human disease to be eradicated. Although routine smallpox vaccination is no longer performed on the general public, the vaccine is still being produced to guard against bioterrorism, biological warfare, and mpox.

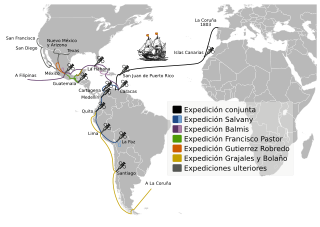

The Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition, commonly referred to as the Balmis Expedition, was a Spanish healthcare mission that lasted from 1803 to 1806, led by Dr Francisco Javier de Balmis, which vaccinated millions of inhabitants of Spanish America and Asia against smallpox. The vaccine was actually transported through children: orphaned boys who sailed with the expedition.

James Phipps was the first person given the experimental cowpox vaccine by Edward Jenner. Jenner knew of a local belief that dairy workers who had contracted a relatively mild infection called cowpox were immune to smallpox, and successfully tested his theory on the 8-years-old James Phipps on 17 May 1796.

Benjamin Jesty was a farmer at Yetminster in Dorset, England, notable for his early experiment in inducing immunity against smallpox using cowpox.

Artificial induction of immunity is immunization achieved by human efforts in preventive healthcare, as opposed to natural immunity as produced by organisms' immune systems. It makes people immune to specific diseases by means other than waiting for them to catch the disease. The purpose is to reduce the risk of death and suffering, that is, the disease burden, even when eradication of the disease is not possible. Vaccination is the chief type of such immunization, greatly reducing the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Joseph Adams, F.L.S. was a British physician and surgeon.

Benjamin Waterhouse was a physician, co-founder and professor of Harvard Medical School. He is most well known for being the first doctor to test the smallpox vaccine in the United States, which he carried out on his own family.

George Pearson FRS (1751–1828) was a British physician, chemist and early advocate of Jenner's cowpox vaccination.

The history of smallpox extends into pre-history. Genetic evidence suggests that the smallpox virus emerged 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. Prior to that, similar ancestral viruses circulated, but possibly only in other mammals, and possibly with different symptoms. Only a few written reports dating from about 500 AD to 1000 AD are considered reliable historical descriptions of smallpox, so understanding of the disease prior to that has relied on genetics and archaeology. However, during the 2nd millennium AD, especially starting in the 16th century, reliable written reports become more common. The earliest physical evidence of smallpox is found in the Egyptian mummies of people who died some 3,000 years ago. Smallpox has had a major impact on world history, not least because indigenous populations of regions where smallpox was non-native, such as the Americas and Australia, were rapidly and greatly reduced by smallpox during periods of initial foreign contact, which helped pave the way for conquest and colonization. During the 18th century the disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year, including five reigning monarchs, and was responsible for a third of all blindness. Between 20 and 60% of all those infected—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease.

Variolation was the method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (Variola) with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual, in the hope that a mild, but protective, infection would result. Only 1–2% of those variolated died from the intentional infection compared to 30% who contracted smallpox naturally. Variolation is no longer used today. It was replaced by the smallpox vaccine, a safer alternative. This in turn led to the development of the many vaccines now available against other diseases.

William Woodville was an English physician and botanist. Convinced by the work of Edward Jenner, he was among the first to promote vaccination. His four volume book on medical botany published between 1790 and 1794 with 300 illustrations of medicinal plants by James Sowerby was an important reference work for physicians in the nineteenth century with a second edition in 1810 followed by a revision in 1832 by William Jackson Hooker and George Spratt.

John Ring (1752–1821) was an English surgeon, vaccination activist, and man of letters.

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microbe or virus into a person or other organism. It is a method of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases. The term "inoculation" is also used more generally to refer to intentionally depositing microbes into any growth medium, as into a Petri dish used to culture the microbe, or into food ingredients for making cultured foods such as yoghurt and fermented beverages such as beer and wine. This article is primarily about the use of inoculation for producing immunity against infection. Inoculation has been used to eradicate smallpox and to markedly reduce other infectious diseases such as polio. Although the terms "inoculation", "vaccination", and "immunization" are often used interchangeably, there are important differences. Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or microbe into a person or other recipient; vaccination is the act of implanting or giving someone a vaccine specifically; and immunization is the development of disease resistance that results from the immune system's response to a vaccine or natural infection.

Onesimus was an African man who was instrumental in the mitigation of the impact of a smallpox outbreak in Boston, Massachusetts. His birth name is unknown. He was enslaved and, in 1706, was given to the New England Puritan minister Cotton Mather, who renamed him. Onesimus introduced Mather to the principle and procedure of the variolation method of inoculation to prevent the disease, which laid the foundation for the development of vaccines. After a smallpox outbreak began in Boston in 1721, Mather used this knowledge to advocate for inoculation in the population, a practice that eventually spread to other colonies. In a 2016 Boston magazine survey, Onesimus was declared one of the "Best Bostonians of All Time".

Derrick Baxby was a British microbiologist and authority on Orthopoxviruses. He was a senior lecturer in medical microbiology at the University of Liverpool.

In 1721, Boston experienced its worst outbreak of smallpox. 5,759 people out of around 10,600 in Boston were infected and 844 were recorded to have died between April 1721 and February 1722. The outbreak motivated Puritan minister Cotton Mather and physician Zabdiel Boylston to variolate hundreds of Bostonians as part of the Thirteen Colonies' earliest experiment with public inoculation. Their efforts would inspire further research for immunizing people from smallpox, placing the Massachusetts Bay Colony at the epicenter of the Colonies' first inoculation debate and changing Western society's medical treatment of the disease. The outbreak also altered social and religious public discourse about disease, as Boston's newspapers published various pamphlets opposing and supporting the inoculation efforts.

Maria Isabel Wittenhall van Zeller (1749–1819) was a pioneer in the use of vaccination against smallpox in Portugal. She became notable for promoting the use of smallpox vaccination at the beginning of the 19th century, particularly in the Porto area.

References

- ↑ Doig, Chris. "John Fewster & family". Thornbury Roots. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ Pearson, George (1798). An Inquiry Concerning the History of the Cowpox, Principally with a View to Supersede and Extinguish the Smallpox. London: J. Johnson. pp. 102–104 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Many sources claim that in 1765, Fewster read a paper to the Medical Society of London titled "Cow pox and its ability to prevent smallpox". However, the Medical Society of London was created in 1773. See:

- History of the Medical Society of London Archived 14 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Wikipedia's article: "Medical Society of London"

- L. Thurston and G. Williams (2015) "An examination of John Fewster’s role in the discovery of smallpox vaccination," Archived 16 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 45 : 173-179; see p.177.

- ↑ Thurston, L; Williams, G (2015). "An examination of John Fewster's role in the discovery of smallpox vaccination". Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh . 45 (2): 173–179. doi: 10.4997/jrcpe.2015.217 . ISSN 1478-2715. PMID 26181536.

- 1 2 Jesty, Robert; Williams, Gareth (2011). "Who invented vaccination?" (PDF). Malta Medical Journal. 23 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ↑ Creighton, Charles (1889). "Chapter 3. Jenner's "Inquiry."". Jenner and Vaccination: A Strange Chapter of Medical History. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. p. 55.

Dr. Jenner has frequently told me that, at the meetings of this Society [the Convivio-Medical, which met at the Ship at Alveston in the southern division of the county, and was attended, among others, by Fewster, the chief authority on cow-pox], he was accustomed to bring forward the reported prophylactic virtues of cowpox, and earnestly to recommend his medical friends to prosecute the inquiry.

- ↑ Baron, John (1838) [1827]. Life of Edward Jenner, MD, with illustrations of his doctrines and selections from his correspondence. Vol. 2. London: Henry Colburn – via Internet Archive.