The golden age of American animation was a period in the history of U.S. animation that began with the popularization of sound synchronized cartoons in 1928 and gradually ended in the 1960s when theatrical animated shorts started to lose popularity to the newer medium of television. Animated media from after the golden age, especially on television, were produced on cheaper budgets and with more limited techniques between the 1960s and 1980s.

Walter Lantz Productions was an American animation studio. It was in operation from 1928 to 1972 and was the principal supplier of animation for Universal Pictures.

John Frederick Hannah was an American animator, writer and director of animated shorts.

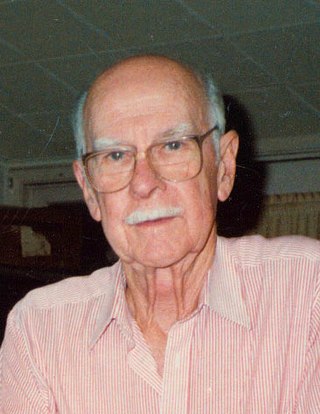

Walter Benjamin Lantz was an American cartoonist, animator, producer and director best known for founding Walter Lantz Productions and creating Woody Woodpecker.

Marc Fraser Davis was a prominent American artist and animator for Walt Disney Animation Studios. He was one of Disney's Nine Old Men, the famed core animators of Disney animated films, and was revered for his knowledge and understanding of visual aesthetics. After his work on One Hundred and One Dalmatians he moved to Walt Disney Imagineering to work on rides for Disneyland and Walt Disney World before retiring in 1978.

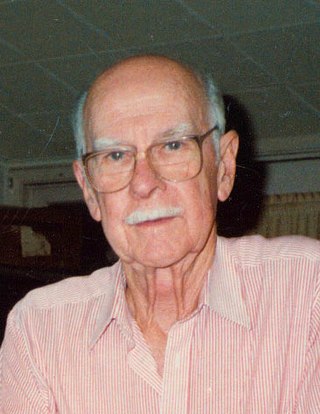

Oliver Martin Johnston Jr. was an American motion picture animator. He was one of Disney's Nine Old Men, and the last surviving at the time of his death from natural causes. He was recognized by The Walt Disney Company with its Disney Legend Award in 1989. His work was recognized with the National Medal of Arts in 2005.

Robert Fred Moore, was an American artist and animator for Walt Disney Animation Studios. Often called "Freddie," he was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. Despite limited formal art training, he rose to prominence at Disney very quickly in the early 1930s, due to his great natural talent and the tremendous appeal of his drawings. His drawings are still greatly admired by animators and animation fans.

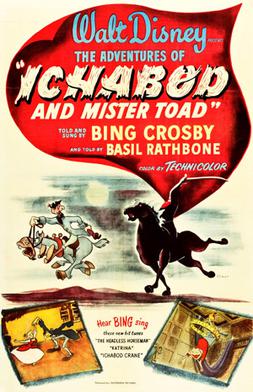

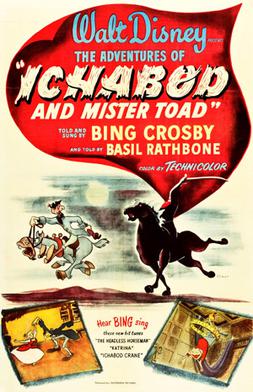

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is a 1949 American animated anthology film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by RKO Radio Pictures. It consists of two segments: the first based on Kenneth Grahame's 1908 children's novel The Wind in the Willows and narrated by Basil Rathbone, and the second based on Washington Irving's 1820 short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and narrated by Bing Crosby. The production was supervised by Ben Sharpsteen, and was directed by Jack Kinney, Clyde Geronimi, and James Algar.

Wolfgang Reitherman, also known and sometimes credited as Woolie Reitherman, was a German–American animator, director and producer and one of the "Nine Old Men" of core animators at Walt Disney Productions. He emerged as a key figure at Disney during the 1960s and 1970s, a transitionary period which saw the death of Walt Disney in 1966, with him serving as director and/or producer on eight consecutive Disney animated feature films from One Hundred and One Dalmatians through The Fox and the Hound.

Edward Robert Sears was an American animator during the Golden Age of American animation. Sears worked for the Fleischer Studios in the late-1920s and early-1930s, and was hired away from Max Fleischer to work at the Walt Disney studio in 1931.

Al Bertino was an American animator best remembered for his work with the Walt Disney Company

Ken Southworth was an English animator, cartoonist and animation instructor who worked for a number of major animation studios throughout his nearly 60-year career, including Walt Disney Studios, Hanna-Barbera, Filmation, Warner Bros. Animation, the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio, Walter Lantz Productions and Clokey Productions. His credits included Disney's Alice in Wonderland and Legend of Sleepy Hollow, as well as Hanna-Barbera's The Flintstones, Space Ghost and Dino Boy, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! and The Smurfs among others.

Walt Stanchfield was an American animator, writer and teacher. Stanchfield is known for work on a series of classic animated feature films at Walt Disney Studios and his mentoring of Disney animators.

Calvin Henry Howard was an American cartoon story artist, animator and director mostly remembered for his work at Walter Lantz Productions and Warner Bros. Cartoons. He was also the voice actor of Gabby Goat in Get Rich Quick Porky and Meathead Dog in Screwball Squirrel.

Mel Shaw was an American animator, design artist, writer, and artist. Shaw was involved in the animation, story design, and visual development of numerous Disney animated films, beginning with Bambi, which was released in 1942. His other animated film credits, usually involving animation design or the story, included The Rescuers in 1977, The Fox and the Hound in 1981, The Black Cauldron in 1985, The Great Mouse Detective in 1986, Beauty and the Beast in 1991, and The Lion King in 1994. He was named a Disney Legend in 2004 for his contributions to The Walt Disney Company.

Donald Ross "Don" Lusk was an American animator and director.

Events in 1916 in animation.

Events in 1911 in animation.

Events in 1904 in animation.

Events in 1903 in animation.