Related Research Articles

John Harrison was a self-educated English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the problem of calculating longitude while at sea.

Paul de Lamerie was a London-based silversmith. The Victoria and Albert Museum describes him as the "greatest silversmith working in England in the 18th century". He was being referred to as the ‘King’s silversmith’ in 1717. Though his mark raises the market value of silver, his output was large and not all his pieces are outstanding. The volume of work bearing de Lamerie's mark makes it almost certain that he subcontracted orders to other London silversmiths before applying his own mark.

George Graham, FRS was an English clockmaker, inventor, and geophysicist, and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to the clock's timekeeping element to replace the energy lost to friction during its cycle and keep the timekeeper oscillating. The escapement is driven by force from a coiled spring or a suspended weight, transmitted through the timepiece's gear train. Each swing of the pendulum or balance wheel releases a tooth of the escapement's escape wheel, allowing the clock's gear train to advance or "escape" by a fixed amount. This regular periodic advancement moves the clock's hands forward at a steady rate. At the same time, the tooth gives the timekeeping element a push, before another tooth catches on the escapement's pallet, returning the escapement to its "locked" state. The sudden stopping of the escapement's tooth is what generates the characteristic "ticking" sound heard in operating mechanical clocks and watches.

A pocket watch is a watch that is made to be carried in a pocket, as opposed to a wristwatch, which is strapped to the wrist.

The Guild Church of St Dunstan-in-the-West is in Fleet Street in the City of London. It is dedicated to Dunstan, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury. The church is of medieval origin, although the present building, with an octagonal nave, was constructed in the 1830s to the designs of John Shaw.

John Arnold was an English watchmaker and inventor.

Thomas Tompion, FRS (1639–1713) was an English clockmaker, watchmaker and mechanician who is still regarded to this day as the "Father of English Clockmaking". Tompion's work includes some of the most historic and important clocks and watches in the world, and can command very high prices whenever outstanding examples appear at auction. A plaque commemorates the house he shared on Fleet Street in London with his equally famous pupil and successor George Graham.

Louisa Perina Courtauld was a French-born English silversmith.

Jean-François Hobler was a Swiss-born, naturalised-English, watchmaker.

Thomas Mudge was an English horologist who invented the lever escapement, a technological improvement to the pocket watch.

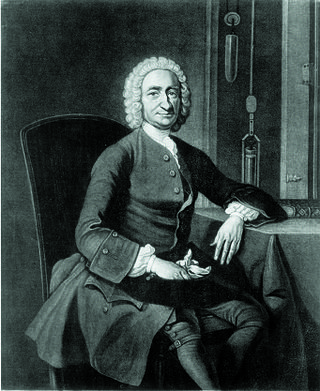

Daniel Quare was an English clockmaker and instrument maker who invented a repeating watch movement in 1680 and a portable barometer in 1695.

Pierre Le Roy (1717–1785) was a French clockmaker. He was the inventor of the detent escapement, the temperature-compensated balance and the isochronous balance spring. His developments are considered as the foundation of the modern precision clock. Le Roy was born in Paris, eldest son of Julien Le Roy, a clockmaker to Louis XV who had worked with Henry Sully, in which place Pierre Le Roy succeeded his father. He had three brothers: Jean-Baptiste Le Roy (1720-1800), a physicist; Julien-David Le Roy (1724–1803), an architect; and Charles Le Roy (1726–1779), a physician and encyclopédiste.

Joseph Knibb (1640–1711) was an English clockmaker of the Restoration era. According to author Herbert Cescinsky, a leading authority on English clocks, Knibb, "next to Tompion, must be regarded as the greatest horologist of his time."

Jean-Antoine Lépine, born as Jean-Antoine Depigny, was an influential watchmaker. He contributed inventions which are still used in watchmaking today and was amongst the finest French watchmakers, who were contemporary world leaders in the field.

Bartholomew Newsam, was clockmaker to Queen Elizabeth I, probably born at York.

(Antoine) Jean-Baptiste Delettrez was a renowned 19th-century French clockmaker.

John Tolson (1691–1737) was an important if elusive English clockmaker and watchmaker of the early eighteenth century who, while not particularly remarkable for his invention, is noteworthy because of the fine quality of his clocks and watches. The style of his early longcase clocks owes much to Thomas Tompion, and the delicate functionality of his early longcase wheelwork echoes Tompion's standards. His short career of 22 years before an early death in 1737 makes his clocks and watches relatively rare and they can command high prices whenever outstanding examples appear at auction.

Victor Kullberg (1824–1890) was one of London's most famous watchmakers, described by one authority as "one of the most brilliant and successful horologists of the 19th century."

References

- 1 2 Kennedy, Maev (22 June 2018). "Lord Nelson's watch expected to fetch up to £450,000 at Sotheby's". the Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Bonhams : Josiah Emery, Charing Cross, London. A very fine and historically important open face pocket watch originally owned by George IV as Prince of Wales No.1057, Circa 1785, Case with London Hallmark for 1800". Bonhams.