The Argentine War of Independence was a secessionist civil war fought from 1810 to 1818 by Argentine patriotic forces under Manuel Belgrano, Juan José Castelli, Martin Miguel de Guemes and José de San Martín against royalist forces loyal to the Spanish crown. On July 9, 1816, an assembly met in San Miguel de Tucumán, declaring independence with provisions for a national constitution.

The May Revolution was a week-long series of events that took place from May 18 to 25, 1810, in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. This Spanish colony included roughly the territories of present-day Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and parts of Brazil. The result was the removal of Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros and the establishment of a local government, the Primera Junta, on May 25.

The Primera Junta or Junta Provisional Gubernativa de las Provincias del Río de la Plata, is the most common name given to the first government of what would eventually become Argentina. It was formed on 25 May 1810, as a result of the events of the May Revolution. The Junta initially only had representatives from Buenos Aires. When it was expanded, as expected, with the addition of representatives from the other cities of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, it became popularly known instead as the Junta Grande or Junta Provisional Gubernativa de Buenos Aires. The Junta operated at El Fuerte, which had been used since 1776 as a residence by the viceroys.

Mariano Moreno was an Argentine lawyer, journalist, and politician. He played a decisive role in the Primera Junta, the first national government of Argentina, created after the May Revolution.

Cornelio Judas Tadeo de Saavedra y Rodríguez was an Argentine military officer and statesman. He was instrumental in the May Revolution, the first step of Argentina's independence from Spain, and became the first head of state of the autonomous country that would become Argentina when he was appointed president of the Primera Junta.

Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros y de la Torre was a Spanish naval officer born in Cartagena. He took part in the Battle of Cape St Vincent and the Battle of Trafalgar, and in the Spanish resistance against Napoleon's invasion in 1808. He was later appointed Viceroy of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, replacing Santiago de Liniers. He disestablished the government Junta of Javier de Elío and quelled the Chuquisaca Revolution and the La Paz revolution. An open cabildo deposed him as viceroy during the May Revolution, but he attempted to be the president of the new government junta, thus retaining power. The popular unrest in Buenos Aires did not allow that, so he resigned. He was banished back to Spain shortly after that, and died in 1829.

Juan José Esteban Paso, was an Argentine politician who participated in the events that started the Argentine War of Independence known as May Revolution of 1810.

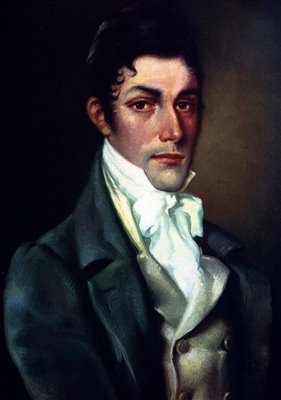

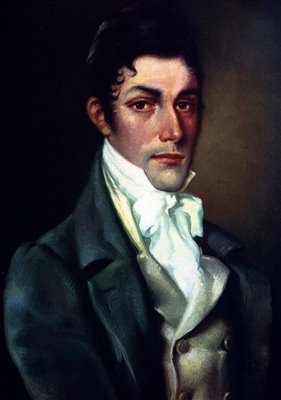

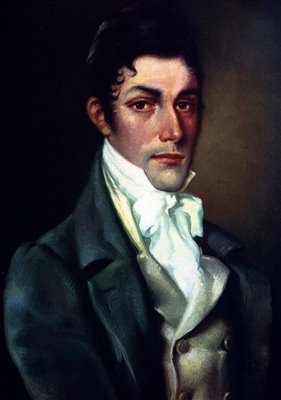

Juan José Castelli was an Argentine lawyer who was one of the leaders of the May Revolution, which led to the Argentine War of Independence. He led an ill-fated military campaign in Upper Peru.

Domingo María Cristóbal French was an Argentine revolutionary who took part in the May Revolution and the Argentine War of Independence.

Miguel de Azcuénaga was an Argentine brigadier. Educated in Spain, at the University of Seville, Azcuénaga began his military career in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata and became a member of the Primera Junta, the first autonomous government of modern Argentina. He was shortly exiled because of his support to the minister Mariano Moreno, and returned to Buenos Aires when the First Triumvirate replaced the Junta. He held several offices since then, most notably being the first Governor intendant of Buenos Aires after the May Revolution. He died at his country house in 1833.

The First Upper Peru campaign was a military campaign of the Argentine War of Independence, which took place in 1810. It was headed by Juan José Castelli, and attempted to expand the influence of the Buenos Aires May Revolution in Upper Peru. There were initial victories, such as in the Battle of Suipacha and the revolt of Cochabamba, but it was finally defeated during the Battle of Huaqui that returned Upper Peru to Royalist influence. Manuel Belgrano and José Rondeau would attempt other similarly ill-fated campaigns; the Royalists in the Upper Peru would be finally defeated by Sucre, whose military campaign came from the North supporting Simón Bolívar.

Martín de Álzaga was a Spanish merchant and politician during the British invasions of the Río de la Plata.

Nicolás Rodriguez Peña was an Argentine politician. Born in Buenos Aires in April 1775, he worked in commerce which allowed him to amass a considerable fortune. Among his several successful businesses, he had a soap factory partnership with Hipólito Vieytes, which was a center of conspirators during the revolution against Spanish rule. In 1805 he was a member of the "Independence Lodge", a masonic lodge, along with other prominent revolutionary patriots such as Juan José Castelli and Manuel Belgrano. This group used to meet in his ranch, then situated in what today is Rodriguez Peña square in Buenos Aires.

Manuel Maximiliano Alberti was an Argentine priest from Buenos Aires when the city was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He had a curacy at Maldonado, Uruguay during the British invasions of the River Plate, and returned to Buenos Aires in time to take part in the May Revolution of 1810. He was chosen as one of the seven members of the Primera Junta, considered the first national government of Argentina. He supported most of the proposals of Mariano Moreno and worked at the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspaper. The internal disputes of the Junta had a negative effect on his health, and he died of a heart attack in 1811.

Domingo Bartolomé Francisco Matheu was a Spanish-born Argentine businessman and politician. He was a member of the Primera Junta, the first national government of modern Argentina, and the second president in the end of the Junta Grande from August to September 1811.

The Mutiny of Álzaga was an ill-fated attempt to remove Santiago de Liniers as viceroy of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. It took place on January 1, 1809, and it was led by the merchant Martín de Álzaga. The troops of Cornelio Saavedra, head of the Regiment of Patricians, defeated it and kept Liniers in power.

The Liniers counter-revolution took place in the Spanish Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata after the May Revolution in 1810. The former viceroy, Santiago de Liniers, led an ill-fated counter-revolutionary attempt from the city of Córdoba, and it was quickly frustrated by the patriotic forces of the newly formed Army of the North. Francisco Ortiz de Ocampo, the leader of the Army of the North, captured the leaders and dispatched them to Buenos Aires as prisoners, but, on the orders of the Primera Junta, they were intercepted and executed before arrival.

The Revolution of October 8, 1812 took place during the Argentine War of Independence. Led by José de San Martín and Carlos María de Alvear, it deposed the First Triumvirate and allowed the creation of the Second Triumvirate, which called the Assembly of Year XIII.

The rise of the Argentine Republic was a process that took place in the first half of the 19th century in Argentina. The Republic has its origins on the territory of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, a colony of the Spanish Empire. The King of Spain appointed a viceroy to oversee the governance of the colony. The 1810 May Revolution staged a coup d'état and deposed the viceroy and, along with the Argentine war of independence, started a process of rupture with the Spanish monarchy with the creation of an independent republican state. All proposals to organize a local monarchy failed, and no local monarch was ever crowned.

The Argentine War of Independence was fought from 1810 to 1818 by Argentine patriotic forces under Manuel Belgrano, Juan José Castelli and José de San Martín against royalist forces loyal to the Spanish crown. On July 9, 1816, an assembly met in San Miguel de Tucumán, declared full independence with provisions for a national constitution.