Related Research Articles

The 12th century is the period from 1101 to 1200 in accordance with the Julian calendar. In the history of European culture, this period is considered part of the High Middle Ages and is sometimes called the Age of the Cistercians. The Golden Age of Islam experienced a significant development, particularly in Islamic Spain.

The 1100s was a decade of the Julian Calendar which began on January 1, 1100, and ended on December 31, 1109.

Year 851 (DCCCLI) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1101 (MCI) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar. It was the 2nd year of the 1100s decade, and the 1st year of the 12th century.

Year 1266 (MCCLXVI) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar.

Victor Emmanuel I was the Duke of Savoy and King of Sardinia (1802–1821).

William I, called the Bad or the Wicked, was the second king of Sicily, ruling from his father's death in 1154 to his own in 1166. He was the fourth son of Roger II and Elvira of Castile.

Charles II, also known as Charles the Lame, was King of Naples, Count of Provence and Forcalquier (1285–1309), Prince of Achaea (1285–1289), and Count of Anjou and Maine (1285–1290); he also styled himself King of Albania and claimed the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1285. He was the son of Charles I of Anjou—one of the most powerful European monarchs in the second half of the 13th century—and Beatrice of Provence. His father granted Charles the Principality of Salerno in the Kingdom of Sicily in 1272 and made him regent in Provence and Forcalquier in 1279.

This is an alphabetical index of people, places, things, and concepts related to or originating from the Byzantine Empire. Feel free to add more, and create missing pages. You can track changes to the articles included in this list from here.

The Republic of Genoa was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in both the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. Between the 16th and 17th centuries it was one of the major financial centers in Europe.

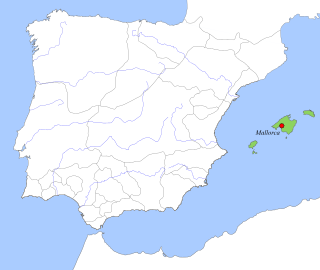

The Crown of Aragon was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona and ended as a consequence of the Spanish War of Succession. At the height of its power in the 14th and 15th centuries, the Crown of Aragon was a thalassocracy controlling a large portion of present-day eastern Spain, parts of what is now southern France, and a Mediterranean empire which included the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, Malta, Southern Italy and parts of Greece.

The House of Grimaldi is associated with the history of the Republic of Genoa, and of the Principality of Monaco. The Grimaldi dynasty is a princely house originating in Genoa, founded by the Genoese leader of the Guelphs, Francesco Grimaldi, who in 1297 took the lordship of Monaco along with his soldiers dressed as Franciscans. In that principality his successors have reigned to the present day. During much of the Ancien Regime the family spent much of its time in the French court, where from 1642 they used their French title of Duke of Valentinois.

Ibn Jubayr, also written Ibn Jubair, Ibn Jobair, and Ibn Djubayr, was an Arab geographer, traveller and poet from al-Andalus. His travel chronicle describes the pilgrimage he made to Mecca from 1183 to 1185, in the years preceding the Third Crusade. His chronicle describes Saladin's domains in Egypt and the Levant which he passed through on his way to Mecca. Further, on his return journey, he passed through Christian Sicily, which had been recaptured from the Muslims only a century before, and he made several observations on the hybrid polyglot culture that flourished there.

The Italian War of 1551–1559, sometimes known as the Habsburg–Valois War and the Last Italian War, began when Henry II of France declared war against Holy Roman Emperor Charles V with the intent of recapturing Italy and ensuring French, rather than Habsburg, domination of European affairs. Historians have emphasized the importance of gunpowder technology, new styles of fortification to resist cannon fire, and the increased professionalization of the soldiers.

The Treaty of Anagni was an accord between the Pope Boniface VIII, James II of Aragon, Philip IV of France, Charles II of Naples, and James II of Majorca. It was signed on 20 June 1295 at Anagni, in central Italy. The chief purpose was to confirm the Treaty of Tarascon of 1291, which ended the Aragonese Crusade. It also dealt with finding a diplomatic solution to the conquest of Sicily by Peter III of Aragón in 1285.

The Pactum Sicardi was a treaty signed on 4 July 836 between the Greek Duchy of Naples, including its satellite city-states of Sorrento and Amalfi, represented by Bishop John IV and Duke Andrew II, and the Lombard Prince of Benevento, Sicard. The treaty was an armistice ending a war between the Greek states and Benevento, during which the Byzantine Empire had not intervened on behalf of its subjects. It was supposed to last five years between the Lombard prince and the Neapolitans. It was a temporary armistice and was distinguished from other treaties such as Pactum Warmundi, which established temporary alliances.

In 1114, an expedition to the Balearic Islands, then a Muslim taifa, was launched in the form of a Crusade. Founded on a treaty of 1113 between the Republic of Pisa and Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Barcelona, the expedition had the support of Pope Paschal II and the participation of many lords of Catalonia and Occitania, as well as contingents from northern and central Italy, Sardinia, and Corsica. The Crusaders were perhaps inspired by the Norwegian king Sigurd I's attack on Formentera in 1108 or 1109 during the Norwegian Crusade. The expedition ended in 1115 in the conquest of the Balearics, but only until the next year. The main source for the event is the Pisan Liber maiolichinus, completed by 1125.

The Invasion of Corsica of 1553 occurred when French, Ottoman, and Corsican exile forces combined to capture the island of Corsica from the Republic of Genoa.

In 1015 and again in 1016 forces from the taifa of Denia, in the east of Muslim Spain (al-Andalus), attacked Sardinia and attempted to establish control over it. In both these years joint expeditions from the maritime republics of Pisa and Genoa repelled the invaders. These Pisan–Genoese expeditions to Sardinia were approved and supported by the Papacy, and modern historians often see them as proto-Crusades. After their victory, the Italian cities turned on each other, and the Pisans obtained hegemony over the island at the expense of their erstwhile ally. For this reason, the Christian sources for the expedition are primarily from Pisa, which celebrated its double victory over the Muslims and the Genoese with an inscription on the walls of its Duomo.

'Abdallah ibn Ishaq ibn Muhammad ibn Ghaniya, known as 'Abdallah ibn Ghaniya was a member of the Banu Ghaniya dynasty who fought against the Almohad Caliphate in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. In c. 1187 he captured the former Bani Ghaniya stronghold of Majorca in the Balearic Islands, and ruled over it until his defeat and death at the hands of the Almohads in 1203.

References

- Everard, J. A. (2000). Brittany and the Angevins: Province and Empire, 1158–1203. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66071-8.

- Lopez, Robert S. and Raymond, Irving W. (1951). Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World. New York: Columbia University Press. LCC 54-11542.

- Samarrai, Alauddin (1980). "Medieval Commerce and Diplomacy: Islam and Europe, A.D. 850–1300". Canadian Journal of History/Annales canadiennes d'histoire, 15:1 (April), pp. 1–21.

- Verzijl, J. H. W. (1972). International Law in Historical Perspective. Vol. IV: Stateless Domain. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-286-0051-5.