The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time; the Huns' arrival is associated with the migration westward of an Iranian people, the Alans. By 370 AD, the Huns had arrived on the Volga, and by 430 the Huns had established a vast, if short-lived, dominion in Europe, conquering the Goths and many other Germanic peoples living outside of Roman borders, and causing many others to flee into Roman territory. The Huns, especially under their King Attila, made frequent and devastating raids into the Eastern Roman Empire. In 451, the Huns invaded the Western Roman province of Gaul, where they fought a combined army of Romans and Visigoths at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, and in 452 they invaded Italy. After the death of Attila in 453, the Huns ceased to be a major threat to Rome and lost much of their empire following the Battle of Nedao (454?). Descendants of the Huns, or successors with similar names, are recorded by neighboring populations to the south, east, and west as having occupied parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia from about the 4th to 6th centuries. Variants of the Hun name are recorded in the Caucasus until the early 8th century.

The Bulgars were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomadic equestrians in the Volga-Ural region, but some researchers say that their ethnic roots can be traced to Central Asia. During their westward migration across the Eurasian steppe, the Bulgar tribes absorbed other tribal groups and cultural influences in a process of ethnogenesis, including Iranian, Finnic and Hunnic tribes. Modern genetic research on Central Asian Turkic people and ethnic groups related to the Bulgars points to an affiliation with Western Eurasian populations. The Bulgars spoke a Turkic language, i.e. Bulgar language of Oghuric branch. They preserved the military titles, organization and customs of Eurasian steppes, as well as pagan shamanism and belief in the sky deity Tangra.

The Alans were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the Alans with the Central Asian Yancai of Chinese sources and with the Aorsi of Roman sources. Having migrated westwards and becoming dominant among the Sarmatians on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, the Alans are mentioned by Roman sources in the 1st century CE. At that time they had settled the region north of the Black Sea and frequently raided the Parthian Empire and the Caucasian provinces of the Roman Empire. From 215–250 CE the Goths broke their power on the Pontic Steppe.

The Xiongnu were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Chinese sources report that Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 209 BC, founded the Xiongnu Empire.

The Sarmatians were a large Iranian confederation that existed in classical antiquity, flourishing from about the fifth century BC to the fourth century AD.

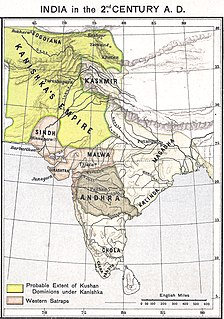

The Kushan Empire was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of modern-day territory of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India, at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great.

Hungarian prehistory spans the period of history of the Hungarian people, or Magyars, which started with the separation of the Hungarian language from other Finno-Ugric or Ugric languages around 800 BC, and ended with the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin around 895 AD. Based on the earliest records of the Magyars in Byzantine, Western European, and Hungarian chronicles, scholars considered them for centuries to have been the descendants of the ancient Scythians and Huns. This historiographical tradition disappeared from mainstream history after the realization of similarities between the Hungarian language and the Uralic languages in the late 18th century. Thereafter, linguistics became the principal source of the study of the Hungarians' ethnogenesis. In addition, chronicles written between the 9th and 15th centuries, the results of archaeological research and folklore analogies provide information on the Magyars' early history.

Xionites, Chionites, or Chionitae were a nomadic people in Transoxiana and Bactria.

The Kidarites, or Kidara Huns, were a dynasty that ruled Bactria and adjoining parts of Central Asia and South Asia in the 4th and 5th centuries. The Kidarites belonged to a complex of peoples known collectively in India as the Huna, and in Europe as the Chionites, and may even be considered as identical to the Chionites. The 5th century Byzantine historian Priscus called them Kidarite Huns, or "Huns who are Kidarites". The Huna/Xionite tribes are often linked, albeit controversially, to the Huns who invaded Eastern Europe during a similar period. They are entirely different from the Hephthalites, who replaced them about a century later.

Old Great Bulgaria or Great Bulgaria, also often known by the Latin names Magna Bulgaria and Patria Onoguria, was a 7th-century Nomadic empire formed by the Onogur Bulgars on the western Pontic–Caspian steppe. Great Bulgaria was originally centered between the Dniester and lower Volga.

The history of the Huns spans the time from before their first secure recorded appearance in Europe around 370 AD to after the disintegration of their empire around 469. The Huns likely entered Western Asia shortly before 370 from Central Asia: they first conquered the Goths and the Alans, pushing a number of tribes to seek refuge within the Roman Empire. In the following years, the Huns conquered most of the Germanic and Scythian barbarian tribes outside of the borders of the Roman Empire. They also launched invasions of both the Asian provinces of Rome and the Sasanian Empire in 375. Under Uldin, the first Hunnic ruler named in contemporary sources, the Huns launched a first unsuccessful large-scale raid into the Eastern Roman Empire in Europe in 408. From the 420s, the Huns were led by the brothers Octar and Ruga, who both cooperated with and threatened the Romans. Upon Ruga's death in 435, his nephews Bleda and Attila became the new rulers of the Huns, and launched a successful raid into the Eastern Roman Empire before making peace and securing an annual tribute and trading raids under the Treaty of Margus. Attila appears to have killed his brother and became sole ruler of the Huns in 445. He would go on to rule for the next eight years, launching a devastating raid on the Eastern Roman Empire in 447, followed by an invasion of Gaul in 451. Attila is traditionally held to have been defeated in Gaul at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, however some scholars hold the battle to have been a draw or Hunnic victory. The following year, the Huns invaded Italy and encountered no serious resistance before turning back.

The Saragurs or Saraguri was a Eurasian Oghur (Turkic) nomadic tribe mentioned in the 5th and 6th centuries. They may be the Sulujie mentioned in the Chinese Book of Sui. They originated from Western Siberia and the Kazakh steppes, from where they were displaced north of the Caucasus by the Sabirs.

This article summarizes the History of the western steppe, which is the western third of the Eurasian steppe, that is, the grasslands of Ukraine and southern Russia. It is intended as a summary and an index to the more-detailed linked articles. It is a companion to History of the central steppe and History of the eastern steppe. All dates are approximate since there are few exact starting and ending dates. This summary article does not list the uncertainties, which are many. For these, see the linked articles.

The Alchon Huns, also known as the Alchono, Alxon, Alkhon, Alkhan, Alakhana and Walxon, were a nomadic people who established states in Central Asia and South Asia during the 4th and 6th centuries CE. They were first mentioned as being located in Paropamisus, and later expanded south-east, into the Punjab and central India, as far as Eran and Kausambi. The Alchon invasion of the Indian subcontinent eradicated the Kidarite Huns who had preceded them by about a century, and contributed to the fall of the Gupta Empire, in a sense bringing an end to Classical India.

Kidara I fl. 350-390 CE) was the first major ruler of the Kidarite Kingdom, which replaced the Indo-Sasanians in northwestern India, in the areas of Kushanshahr, Gandhara, Kashmir and Punjab.

The term Iranian Huns is sometimes used for a group of different tribes that lived in Afghanistan and neighboring areas between the fourth and seventh centuries and expanded into northwest India. They are roughly equivalent to the Hunas. They also threatened the northeast borders of Sasanian Persia and forced the Shahs to lead many ill-documented campaigns against them.

The origin of the Huns and their relationship to other peoples identified in ancient sources as Iranian Huns such as the Xionites, the Alchon Huns, the Kidarites, the Hephthalites, the Nezaks, and the Huna, has been the subject of long-term scholarly controversy. In 1757, Joseph de Guignes first proposed that the Huns were identical to the Xiongnu. The thesis was then popularized by Edward Gibbon. Since that time scholars have debated the proposal on its linguistic, historical, and archaeological merits. In the mid-twentieth century, the connection was attacked by the Sinologist Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen and largely fell out of favor. Some recent scholarship has argued in favor of some form of link, and the theory returned to the mainstream, being particularly supported by archaeogenetic studies.

Hind was the name of a southeastern Sasanian province lying near the Indus River. The boundaries of the province are obscure. The Austrian historian and numismatist Nikolaus Schindel has suggested that the province may have corresponded to the Sindh region, where the Sasanians notably minted unique gold coins of themselves. According to the modern historian C. J. Brunner, the province possibly included—whenever jurisdiction was established—the areas of the Indus River, including the southern part of Punjab.