Related Research Articles

A riddle is a statement, question or phrase having a double or veiled meaning, put forth as a puzzle to be solved. Riddles are of two types: enigmas, which are problems generally expressed in metaphorical or allegorical language that require ingenuity and careful thinking for their solution, and conundra, which are questions relying for their effects on punning in either the question or the answer.

Nizami Ganjavi, Nizami Ganje'i, Nizami, or Nezāmi, whose formal name was Jamal ad-Dīn Abū Muḥammad Ilyās ibn-Yūsuf ibn-Zakkī, was a 12th-century Muslim poet. Nizami is considered the greatest romantic epic poet in Persian literature, who brought a colloquial and realistic style to the Persian epic. His heritage is widely appreciated in Afghanistan, Republic of Azerbaijan, Iran, the Kurdistan region and Tajikistan.

Persian literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources have been within Greater Iran including present-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, the Caucasus, and Turkey, regions of Central Asia, South Asia and the Balkans where the Persian language has historically been either the native or official language. For example, Rumi, one of the best-loved Persian poets, born in Balkh or Wakhsh, wrote in Persian and lived in Konya, at that time the capital of the Seljuks in Anatolia. The Ghaznavids conquered large territories in Central and South Asia and adopted Persian as their court language. There is thus Persian literature from Iran, Mesopotamia, Azerbaijan, the wider Caucasus, Turkey, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Tajikistan and other parts of Central Asia, as well as the Balkans. Not all Persian literature is written in Persian, as some consider works written by ethnic Persians or Iranians in other languages, such as Greek and Arabic, to be included. At the same time, not all literature written in Persian is written by ethnic Persians or Iranians, as Turkic, Caucasian, Indic and Slavic poets and writers have also used the Persian language in the environment of Persianate cultures.

The qaṣīda is an ancient Arabic word and form of poetry, often translated as ode, passed to other cultures after the Arab Muslim expansion.

Fārsīwān is a contemporary designation for Persian speakers in Afghanistan and its diaspora elsewhere. More specifically, it was originally used to refer to a distinct group of farmers in Afghanistan and urban dwellers. In Afghanistan, original Farsiwans are found predominantly in Herat and Farah provinces. They are roughly the same as the Persians of eastern Iran. The term excludes the Hazāra and Aymāq tribes, who also speak dialects of Persian.

Abu'l-Hasan Ali ibn Julugh Farrukhi Sistani, better known as Farrukhi Sistani was one of the most prominent Persian court poets in the history of Persian literature. Initially serving a dehqan in Sistan and the Muhtajids in Chaghaniyan, Farrukhi entered the service of the Ghaznavids in 1017, where he became the panegyrist of its rulers, Mahmud and Mas'ud I, as well as numerous viziers and princes.

Amīr ash-Shu‘arā’ Abū Abdullāh Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Malik Mu‘izzī was a poet who ranks as one of the great masters of the Persian panegyric form known as qasideh.

Abū ‘Umar ‘Uthmān b. ‘Umar Mukhtārī Ghaznavī was a Persian poet of the Ghaznavids, an empire originating from Ghazna located in Afghanistan. He had patrons at the courts of the Qarakhānids, the Seljūqs of Kirman, and the Ismaili ruler of Tabas.

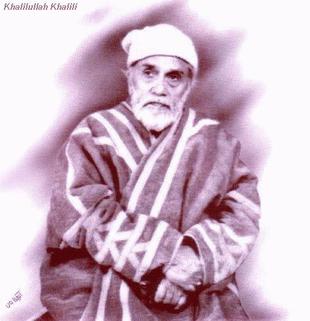

Khalilullah Khalili was Afghanistan's foremost 20th century poet as well as a noted historian, university professor, diplomat and royal confidant. He was the last of the great classical Persian poets and among the first to introduce modern Persian poetry and Nimai style to Afghanistan. He had also expertise in Khorasani style and was a follower of Farrukhi Sistani. Almost alone among Afghanistan's poets, he enjoyed a following in Iran where his selected poems have been published. His works have been praised by renowned Iranian literary figures and intellectuals. Many see him as the greatest contemporary poet of the Persian language in Afghanistan. He is also known for his major work "Hero of Khorasan", a controversial biography of Habībullāh Kalakānī, Emir of Afghanistan in 1929.

Ayatullah Sheikh Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, commonly known as Akhund Khurasani was a Shia jurist and political activist.

Saib Tabrizi was an Iranian poet, regarded as one of the greatest masters of a form of classical Persian lyric poetry characterized by rhymed couplets, known as the ghazal. He also established the "Indian style" in the literature of his native language, Azerbaijani Turkic, in which he is known to have written 17 ghazals and molammaʿs.

Waṣf is an ancient style of Arabic poetry, which can be characterised as descriptive verse. The concept of waṣf was also borrowed into Persian, which developed its own rich poetic tradition in this mode.

Riddles are historically a significant genre of Arabic literature. The Qur’an does not contain riddles as such, though it does contain conundra. But riddles are attested in early Arabic literary culture, 'scattered in old stories attributed to the pre-Islamic bedouins, in the ḥadīth and elsewhere; and collected in chapters'. Since the nineteenth century, extensive scholarly collections have also been made of riddles in oral circulation.

Metiochus and Parthenope is an ancient Greek novel that, in a translation by the eleventh-century poet ‘Unṣurī, also became the Persian romance epic Vāmiq u ‘Adhrā, and the basis for a wide range of stories about the 'lover and the virgin' in medieval and modern Islamicate cultures.

The Persian term for riddle is chīstān, literally 'what is it?', a word that frequently occurs in the opening formulae of Persian riddles. However, the Arabic loan-word lughaz is also used. Traditional Persian rhetorical manuals almost always handle riddles, but Persian riddles have enjoyed little modern scholarly attention. Yet in the assessment of A. A. Seyed-Gohrab, 'Persian literary riddles provide us with some of the most novel and intricate metaphors and images in Persian poetry'.

Hunar-nāma is a 487-distich Persian mathnavī poem composed by ‘Uthmān Mukhtārī at Tabas in the period 500-508, when he was at the court of Seljuqs in Kirmān. The poem is dedicated to the ruler of Tabas, Yamīn al-Dowla (aka Ḥisām ad-Dīn Yamīn ad-Dowla Shams al-Ma‘ālī Abū ’l-Muẓaffar Amīr Ismā‘īl Gīlakī, and can be read as a 'letter of application' demonstrating Mukhtārī's skill as a court poet. It has been characterised as 'perhaps the most interesting of the poems dedicated to Gīlākī'.

Alireza Korangy is an Iranian-American literary critic, philologist and linguist. He is currently faculty at the American University of Beirut. He was previously an Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia. Korangy also taught at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is the editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Persian Literature and is known for his works on Persian poetry, Iranian and Semitic philology and linguistics, and folklore.

Ayatollah Sheikh Hasanali Morvarid was a senior Iranian Shia scholar and teacher.

Ali-Asghar Seyed-Ghorab is an Iranian literary scholar and Professor of Persian and Iranian Studies at Utrecht University. Previously, he was Associate Professor of Persian Language and Literature in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at Leiden University. He is a fellow of the Young Academy of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2023 he was elected a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Indian style, also known as Sabk-i Hindi was a literary style in Persian poetry. The term was coined because poets and writers who were affiliated with Indian courts during the Mughal era were particularly notable for incorporating the characteristics typically associated with this style into their works. Some modern Iranian scholars have recommended using the names "sabk-i Isfahani" or "sabk-i Safavi" instead of sabk-i Hindi because the poets of the Safavid court in Isfahan during the 17th and early 18th century wrote in a similar manner.

References

- ↑ 'Persian Poetry', in The Princeton Handbook of World Poetries, ed. by Roland Greene and Stephen Cushman (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), p. 419.

- ↑ A. A. Seyed-Gohrab, Courtly Riddles: Enigmatic Embellishments in Early Persian Poetry (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2010), p. 20; Angela Sadeghi Tehrani, 'Modernist Poetry in Iran and the Pioneers', Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2.7 (July 2014), 167-69 (p. 167).

- ↑ A. A. Seyed-Gohrab, Courtly Riddles: Enigmatic Embellishments in Early Persian Poetry (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2010), p. 20.

- ↑ Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, 'Stylistic Continuities in Classical Persian Poetry: Reflections on Manuchehri from Dāmghān and Amir Mo‘ezzi', in The Age of the Seljuqs, ed. by Edmund Herzig and Sarah Stewart, The Idea of Iran, 6 (I. B. Tauris).

- ↑ Angela Sadeghi Tehrani, 'Modernist Poetry in Iran and the Pioneers', Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2.7 (July 2014), 167-69 (p. 168).

- ↑ Sabk-i Khurāsānī dar shiʻr-i Fārsī : barrasī-i mukhtaṣṣāt-i sabkī-i shiʻr-i Fārsī az āghāz-i ẓuhūr tā pāyān-i qarn-i panjum hijrī [The Khorasani style in Persian poetry: studies of the stylistic character of Persian poetry from its origins to the end of the fifth century of the Hegira] ([Tihrān]: Intishārāt-i Firdaws, 199-? [first publ. 1971]).

- ↑ A. A. Seyed-Gohrab, Courtly Riddles: Enigmatic Embellishments in Early Persian Poetry (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2010), pp. 39-42, drawing on Julie Scott Meisami, 'Palaces and Paradises: Palace Description in Medieval Persian Poetry', in Islamic Art and Literature, ed. by O. Grabar and C. Robinson (Princeton, 2001), pp. 21-54.