Related Research Articles

Diffraction is the deviation of waves from straight-line propagation without any change in their energy due to an obstacle or through an aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a secondary source of the propagating wave. Diffraction is the same physical effect as interference, but interference is typically applied to superposition of a few waves and the term diffraction is used when many waves are superposed.

Wave-particle duality is the concept in quantum mechanics that fundamental entities of the universe, like photons and electrons, exhibit particle or wave properties according to the experimental circumstances. It expresses the inability of the classical concepts such as particle or wave to fully describe the behavior of quantum objects. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, light was found to behave as a wave then later discovered to have a particulate behavior, whereas electrons behaved like particles in early experiments then later discovered to have wavelike behavior. The concept of duality arose to name these seeming contradictions.

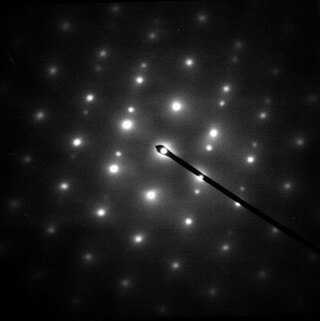

Electron diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of electron beams due to elastic interactions with atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the electrons. The negatively charged electrons are scattered due to Coulomb forces when they interact with both the positively charged atomic core and the negatively charged electrons around the atoms. The resulting map of the directions of the electrons far from the sample is called a diffraction pattern, see for instance Figure 1. Beyond patterns showing the directions of electrons, electron diffraction also plays a major role in the contrast of images in electron microscopes.

Neutron diffraction or elastic neutron scattering is the application of neutron scattering to the determination of the atomic and/or magnetic structure of a material. A sample to be examined is placed in a beam of thermal or cold neutrons to obtain a diffraction pattern that provides information of the structure of the material. The technique is similar to X-ray diffraction but due to their different scattering properties, neutrons and X-rays provide complementary information: X-Rays are suited for superficial analysis, strong x-rays from synchrotron radiation are suited for shallow depths or thin specimens, while neutrons having high penetration depth are suited for bulk samples.

A synchrotron light source is a source of electromagnetic radiation (EM) usually produced by a storage ring, for scientific and technical purposes. First observed in synchrotrons, synchrotron light is now produced by storage rings and other specialized particle accelerators, typically accelerating electrons. Once the high-energy electron beam has been generated, it is directed into auxiliary components such as bending magnets and insertion devices in storage rings and free electron lasers. These supply the strong magnetic fields perpendicular to the beam that are needed to stimulate the high energy electrons to emit photons.

In many areas of science, Bragg's law, Wulff–Bragg's condition, or Laue–Bragg interference are a special case of Laue diffraction, giving the angles for coherent scattering of waves from a large crystal lattice. It describes how the superposition of wave fronts scattered by lattice planes leads to a strict relation between the wavelength and scattering angle. This law was initially formulated for X-rays, but it also applies to all types of matter waves including neutron and electron waves if there are a large number of atoms, as well as visible light with artificial periodic microscale lattices.

The Ewald sphere is a geometric construction used in electron, neutron, and x-ray diffraction which shows the relationship between:

The Davisson–Germer experiment was a 1923–1927 experiment by Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer at Western Electric, in which electrons, scattered by the surface of a crystal of nickel metal, displayed a diffraction pattern. This confirmed the hypothesis, advanced by Louis de Broglie in 1924, of wave-particle duality, and also the wave mechanics approach of the Schrödinger equation. It was an experimental milestone in the creation of quantum mechanics.

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies interference, diffraction, polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric optics is not valid. This usage tends not to include effects such as quantum noise in optical communication, which is studied in the sub-branch of coherence theory.

Electron scattering occurs when electrons are displaced from their original trajectory. This is due to the electrostatic forces within matter interaction or, if an external magnetic field is present, the electron may be deflected by the Lorentz force. This scattering typically happens with solids such as metals, semiconductors and insulators; and is a limiting factor in integrated circuits and transistors.

The dynamical theory of diffraction describes the interaction of waves with a regular lattice. The wave fields traditionally described are X-rays, neutrons or electrons and the regular lattice are atomic crystal structures or nanometer-scale multi-layers or self-arranged systems. In a wider sense, similar treatment is related to the interaction of light with optical band-gap materials or related wave problems in acoustics. The sections below deal with dynamical diffraction of X-rays.

Grazing incidence diffraction (GID) is a technique for interrogating a material using small incidence angles for an incoming wave, often leading to the diffraction being surface sensitive. It occurs in many different areas:

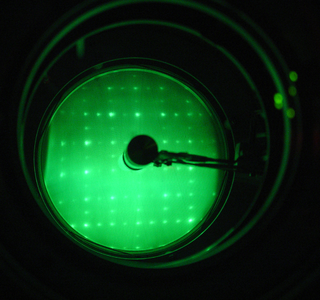

Low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) is a technique for the determination of the surface structure of single-crystalline materials by bombardment with a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (30–200 eV) and observation of diffracted electrons as spots on a fluorescent screen.

In solid-state physics, an energy gap or band gap is an energy range in a solid where no electron states exist, i.e. an energy range where the density of states vanishes.

The GW approximation (GWA) is an approximation made in order to calculate the self-energy of a many-body system of electrons. The approximation is that the expansion of the self-energy Σ in terms of the single particle Green's function G and the screened Coulomb interaction W

The coherent potential approximation (CPA) is a method, in theoretical physics, of finding the averaged Green's function of an inhomogeneous system. The Green's function obtained via the CPA then describes an effective medium whose scattering properties represent the averaged scattering properties of the disordered system being approximated. It is often described as the 'best' single-site theory for obtaining the averaged Green's function. It is perhaps most famous for its use in describing the physical properties of alloys and disordered magnetic systems, although it is also a useful concept in understanding how sound waves scatter in a material which displays spatial inhomogeneity. The coherent potential approximation was first described by Paul Soven, and its application in the context of calculations of the electronic structure of materials was pioneered by Balász Győrffy.

In materials science, paracrystalline materials are defined as having short- and medium-range ordering in their lattice but lacking crystal-like long-range ordering at least in one direction.

The Korringa–Kohn–Rostoker (KKR) method is used to calculate the electronic band structure of periodic solids. In the derivation of the method using multiple scattering theory by Jan Korringa and the derivation based on the Kohn and Rostoker variational method, the muffin-tin approximation was used. Later calculations are done with full potentials having no shape restrictions.

The multislice algorithm is a method for the simulation of the elastic scattering of an electron beam with matter, including all multiple scattering effects. The method is reviewed in the book by John M. Cowley, and also the work by Ishizuka. The algorithm is used in the simulation of high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HREM) micrographs, and serves as a useful tool for analyzing experimental images. This article describes some relevant background information, the theoretical basis of the technique, approximations used, and several software packages that implement this technique. Some of the advantages and limitations of the technique and important considerations that need to be taken into account are described.

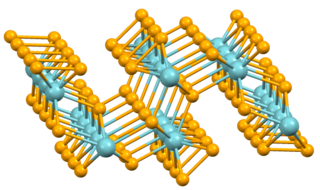

Niobium triselenide is an inorganic compound belonging to the class of transition metal trichalcogenides. It has the formula NbSe3. It was the first reported example of one-dimensional compound to exhibit the phenomenon of sliding charge density waves. Due to its many studies and exhibited phenomena in quantum mechanics, niobium triselenide has become the model system for quasi-1-D charge density waves.

References

- ↑ Als-Nielsen, Jens; McMorrow, Des (2011). Elements of Modern X‐ray Physics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119998365. ISBN 9781119998365.

- ↑ Cowley, J. M. (1995). Diffraction physics. North-Holland personal library (3rd ed.). Amsterdam ; New York: Elsevier Science B.V. ISBN 978-0-444-82218-5.

- ↑ Cullity, B. D. (2001). Elements of x-ray diffraction. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-201-61091-4.

- ↑ Authier, Andre (2003-11-06). "Elementary dynamical theory". Dynamical Theory of X-Ray Diffraction. Oxford University PressOxford. pp. 68–112. ISBN 0-19-852892-2 . Retrieved 2025-01-19.

- ↑ Humphreys, C J (1979-11-01). "The scattering of fast electrons by crystals". Reports on Progress in Physics. 42 (11): 1825–1887. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/42/11/002. ISSN 0034-4885.

- ↑ Peng, L -M; Dudarev, S L; Whelan, M J (2004-01-08), "Dynamical Theory Ii. Transmission High-Energy Electron Diffraction", High-Energy Electron Diffraction And Microscopy, Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 75–116, ISBN 978-0-19-850074-2 , retrieved 2025-01-19

- ↑ J B Pendry (1971-11-18). "Ion core scattering and low energy electron diffraction. I". Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 4 (16): 2501–2513. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/4/16/015. ISSN 0022-3719.

- ↑ Maksym, P.A.; Beeby, J.L. (1981). "A theory of rheed". Surface Science. 110 (2): 423–438. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(81)90649-X.