History

It is often speculated that the shield was developed for mounted cavalry, and that its dimensions correlate to the approximate space between a horse's neck and its rider's thigh. [4] The narrow bottom is seen to be protecting the rider's left leg, and the pronounced upper curve, the rider's shoulder and torso. [3] This is seen as an improvement over more common circular shields, such as bucklers, which afforded poor protection to the horseman's left flank, especially when charging with a lance. [4]

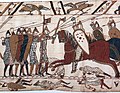

Kite shields gained popularity throughout Western Europe during the 1000s. [4] [5] In the Bayeux Tapestry, most of the English are depicted on foot with kite shields, while a minority still use round shields. [4] Aside from Normandy, they also appeared early on in parts of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. It is unclear from which of these three regions the design originated. [2] A theory is that the kite shield was inherited by the Normans from their Viking predecessors. [2] However, no documentation or remains of kite shields from the Viking era have been discovered, and they were not ideally suited to the Vikings' highly mobile light infantry. [2] Kite shields were depicted primarily on eleventh century illustrations, largely in Western Europe and the Byzantine Empire, but also in the Caucasus, the Fatimid Caliphate, and among the Kievan Rus'. [2] For example, an eleventh century silver engraving of Saint George recovered from Bochorma, Georgia, depicts a kite shield, as do other isolated pieces of Georgian art dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. [2] Kite shields also appear on the Bab al-Nasr in Cairo, which was constructed around 1087. Arab historians usually described them as tariqa or januwiyya. [2]

Kite shields were introduced in large numbers to the Middle East by the First Crusade, when Arab and Byzantine soldiers first observed the type being carried by Norman crusaders; these left such a favourable impression on Byzantium that they had entirely superseded round shields in the Komnenian army by the mid twelfth century. [2]

Around the mid to late twelfth century, traditional kite shields were largely replaced by a variant in which the top was flat, rather than rounded. This change made it easier for a soldier to hold the shield upright without limiting his field of vision. [5] Flat-topped kite shields were later phased out by most Western European armies in favour of much smaller, more compact heater shields . [5] However, they were still being carried by Byzantine infantry well into the thirteenth century. [3]

Construction

To compensate for their awkward nature, kite shields were equipped with enarmes, which gripped the shield tight to the arm and facilitated keeping it in place even when a knight relaxed his arm; this was a significant departure from most earlier circular shields as they possessed only a single handle. [5] Some examples were apparently also fitted with an additional guige strap that allowed the shield to be slung over one shoulder when not in use. [5] Byzantine infantry frequently carried kite shields on their backs while on the march, sometimes upside down. [3] At the time of the First Crusade, most kite shields were still fitted with a domed metal centrepiece (shield boss), although the use of enarmes would have rendered them unnecessary. [2] The shields may have been fitted with both enarmes and an auxiliary hand grip. [5]

A typical kite shield was at least three to five feet high, being constructed of laminated wood, stretched animal hide, and iron components. [3] Records from Byzantium in the 1200s suggests the shield frame accounted for most of the wood and iron; its body was constructed out of hide, parchment, or hardened leather, similar to the material used on drum faces. [3]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.