Refrigeration is any of various types of cooling of a space, substance, or system to lower and/or maintain its temperature below the ambient one. Refrigeration is an artificial, or human-made, cooling method.

Rockland County is the second-southernmost county on the west side of the Hudson River in the U.S. state of New York, after Richmond County. It is part of the New York metropolitan area. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the county's population is 338,329, making it the state's third-most densely populated county outside New York City after Nassau and neighboring Westchester Counties. The county seat and largest hamlet is New City. Rockland County is accessible via the New York State Thruway, which crosses the Hudson River to Westchester at the Tappan Zee Bridge over the Tappan Zee, ten exits up from the NYC border, as well as the Palisades Parkway five exits up from the George Washington Bridge. The county's name derives from "rocky land", as the area has been aptly described, largely due to the Hudson River Palisades. The county is part of the Hudson Valley region of the state.

Clarkstown is a town in Rockland County, New York, United States. The town is on the eastern border of the county, located north of the town of Orangetown, east of the town of Ramapo, south of the town of Haverstraw, and west of the Hudson River. As of the 2020 census, the town had a total population of 86,855. The hamlet of New City, the county seat of Rockland County, is also the seat of town government and of the Clarkstown Police Department, the county sheriff's office, and the county correctional facility. New City makes up about 41.47% of the town's population.

Congers is a suburban hamlet and census-designated place in the town of Clarkstown, Rockland County, New York, United States. It is located north of Valley Cottage, east of New City, across Lake DeForest, south of Haverstraw, and west of the Hudson River. It lies 19 miles (31 km) north of New York City's Bronx boundary. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,532.

Valley Cottage is a hamlet and census-designated place in the town of Clarkstown, New York, United States. It is located northeast of West Nyack, northwest of Central Nyack east of Bardonia, south of Congers, northwest of Nyack, and west of Upper Nyack. The population was 9,107 at the 2010 census.

Haverstraw is a village incorporated in 1854 in the town of Haverstraw in Rockland County, New York, United States. It is located north of Congers, southeast of West Haverstraw, east of Garnerville, northeast of New City, and west of the Hudson River at its widest point. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,323.

The Hudson Valley comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to Yonkers in Westchester County, bordering New York City.

Pollepel Island is a 6.5-acre (26,000 m2) uninhabited island in the Hudson River in New York, United States. The principal feature on the island is Bannerman's Castle, an abandoned military surplus warehouse.

Rockland Lake State Park is a 1,133-acre (4.59 km2) state park located in the hamlets of Congers and Valley Cottage in the eastern part of the Town of Clarkstown in Rockland County, New York, United States. The park is located on a ridge of Hook Mountain above the west bank of the Hudson River. Included within the park is the 256-acre (1.04 km2) Rockland Lake.

Blauvelt State Park is a 644-acre (2.61 km2) undeveloped state park located in the Town of Orangetown in Rockland County, New York, near the Hudson River Palisades. The park's land occupies the site of the former Camp Bluefields, a rifle range used to train members of the New York National Guard prior to World War I. The park is located south of Nyack.

Rondout, is situated in Ulster County, New York, on the Hudson River at the mouth of Rondout Creek. Originally a maritime village, the arrival of the Delaware and Hudson Canal helped create a city that dwarfed nearby Kingston. Rondout became the third largest port on the Hudson River. Rondout merged with Kingston in 1872. It now includes the Rondout–West Strand Historic District.

Camp Shanks was a United States Army installation in the Orangetown, New York area. Named after Major General David C. Shanks, it was situated near the juncture of the Erie Railroad and the Hudson River. The camp was the largest U.S. Army embarkation camp used during World War II.

Stillwater Lake is a reservoir that covers approximately 315 acres (1.27 km2). The lake is located in Pocono Summit, Pennsylvania, at an elevation of 1,811 feet (552 m). Fed by Dotter's Run, Hawkeye Run, Pocono Summit Creek, and several underground springs, the lake flows out to Lake Naomi via Tunkhannock Creek. There are several Tunkhannock Creeks in the Pocono Mountains in Northeastern Pennsylvania. This one merges with the Tobyhanna at Pocono Lake. The Tobyhanna flows into the Lehigh, and ultimately into Delaware Bay.

The Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries was a world's fair held in the Bronx, New York City, United States, in 1918. Meant to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Bronx's settlement, it failed to become popular, as the exposition was held during World War I. After the exposition ended, the site was used for an amusement park called Starlight Park.

Starlight Park is a public park located along the Bronx River in the Bronx in New York City. Starlight Park stands on the site of an amusement park of the same name that operated in the first half of the 20th century.

Iceland, once known as Cuba, was an ice farming and lumbering community in eastern Nevada County, California. It was located between Boca, California and the Nevada state line, about 1 1/2 miles south of Floriston, California and 9 miles east of Truckee, California. It lay near where Gray Creek flows into the Truckee River.

The recorded history of Rockland County, New York begins on February 23, 1798, when the county was split off from Orange County, New York and formed as its own administrative division of the state of New York. It is located 6 miles (9.7 km) north-northwest of New York City, and is part of the New York Metropolitan Area. The county seat is the hamlet of New City. The name comes from rocky land, an early description of the area given by settlers. Rockland is New York's southernmost county west of the Hudson River. It is suburban in nature, with a considerable amount of scenic designated parkland. Rockland County does not border any of the New York City boroughs, but is only 9.5 miles (15.3 km) north of Manhattan at the counties' two respective closest points

Polaris was a historic ice farming community located nearly 3 miles east of Truckee, approximately at the intersection of modern day Glenshire Drive and Quail Lane.

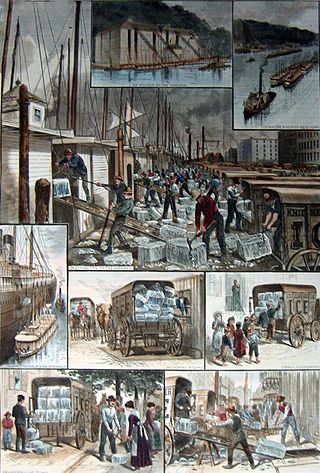

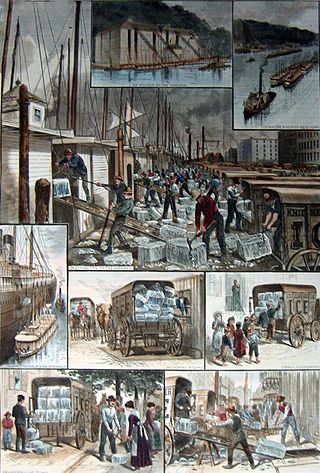

The ice trade, also known as the frozen water trade, was a 19th-century and early 20th-century industry, centering on the east coast of the United States and Norway, involving the large-scale harvesting, transport and sale of natural ice, and later the making and sale of artificial ice, for domestic consumption and commercial purposes. Ice was cut from the surface of ponds and streams, then stored in ice houses, before being sent on by ship, barge or railroad to its final destination around the world.

Rockland Lake may refer to: