Scotch whisky is malt whisky or grain whisky, made in Scotland.

A mortar and pestle is a set of two simple tools used to prepare ingredients or substances by crushing and grinding them into a fine paste or powder in the kitchen, laboratory, and pharmacy. The mortar is characteristically a bowl, typically made of hard wood, metal, ceramic, or hard stone such as granite. The pestle is a blunt, club-shaped object. The substance to be ground, which may be wet or dry, is placed in the mortar where the pestle is pounded, pressed, or rotated into the substance until the desired texture is achieved.

Quern-stones are stone tools for hand-grinding a wide variety of materials, especially for various types of grains. They are used in pairs. The lower stationary stone of early examples is called a saddle quern, while the upper mobile stone is called a muller, rubber, or handstone. The upper stone was moved in a back-and-forth motion across the saddle quern. Later querns are known as rotary querns. The central hole of a rotary quern is called the eye, and a dish in the upper surface is known as the hopper. A handle slot contained a handle which enabled the rotary quern to be rotated. They were first used in the Neolithic era to grind cereals into flour.

Grain whisky normally refers to any whisky made, at least in part, from grains other than malted barley. Frequently used grains include maize, wheat, and rye. Grain whiskies usually contain some malted barley to provide enzymes needed for mashing and are required to include it if they are produced in Ireland or Scotland. Whisky made only from malted barley is generally called "malt whisky" rather than grain whisky. Most American and Canadian whiskies are grain whiskies.

Kilmaurs is a village in East Ayrshire, Scotland which lies just outside of the largest settlement in East Ayrshire, Kilmarnock. It lies on the Carmel Water, 21 miles southwest of Glasgow. Population recorded for the village in the 2001 Census recorded 2,601 people resided in the village It was in the Civil Parish of Kilmaurs.

Dalgarven Mill is near Kilwinning, in the Garnock Valley, North Ayrshire, Scotland and it is home to the Museum of Ayrshire Country Life and Costume. The watermill has been completely restored over a number of years and is run by the independent Dalgarven Mill Trust.

Dunlop is a village and parish in East Ayrshire, Scotland. It lies on the A735, north-east of Stewarton, seven miles from Kilmarnock. The road runs on to Lugton and the B706 enters the village from Beith and Burnhouse.

Kerelaw Castle is a castle ruin. It is situated on the coast of North Ayrshire, Scotland in the town of Stevenston.

Thirlage was a feudal servitude under Scots law restricting manorial tenants in the milling of their grain for personal or other uses. Vassals in a feudal barony were thirled to their local mill owned by the feudal superior. People so thirled were called suckeners and were obliged to pay customary dues for use of the mill and help maintain it.

Cleeves Cove or Blair Cove is a solutional cave system on the Dusk Water in North Ayrshire, Scotland, close to the town of Dalry.

Riccarton is a village and parish in East Ayrshire, Scotland. It lies across the River Irvine from Kilmarnock, this river forming the boundary between Riccarton and Kilmarnock parishes, and also between the historical districts of Kyle and Cunningham. The name is a corruption of 'Richard's town', traditionally said to refer to Richard Wallace, the uncle of Sir William Wallace. The parish also contains the village of Hurlford.

The Ballochmyle Viaduct is the tallest extant railway viaduct in Britain. It is 169 feet (52 m) high, and carries the railway over the River Ayr near Mauchline and Catrine in East Ayrshire, Scotland. It carries the former Glasgow and South Western Railway line between Glasgow and Carlisle.

Kilmaurs Place, The Place or Kilmaurs House, is an old mansion house and the ruins of Kilmaurs Tower grid reference NS41234112 are partly incorporated, Kilmaurs, East Ayrshire, Scotland. The house stands on a prominence above the Carmel Water and has a commanding view of the surrounding area. Once the seat of the Cunningham Earls of Glencairn it ceased to be the main residence after 1484 when Finlaystone became the family seat. Not to be confused with Kilmaurs Castle that stood on the lands of Jocksthorn Farm.

Bere, pronounced "bear," is a six-row barley currently cultivated mainly on 5-15 hectares of land in Orkney, Scotland. It is also grown in Shetland, Caithness and on a very small scale by a few crofters on some of the Western Isles, i.e. North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, Islay and Barra. It is probably Britain's oldest cereal in continuous commercial cultivation.

Monkton is a small village in the parish of Monkton and Prestwick in South Ayrshire, Scotland. The town of Prestwick is around 1+1⁄2 miles south of the village, and it borders upon Glasgow Prestwick Airport.

Dunduff Castle is a restored stair-tower in South Ayrshire, Scotland, built on the hillside of Brown Carrick Hills above the Drumbane Burn, and overlooking the sea above the village of Dunure.

Lochlea or Lochlie was situated in a low-lying area between the farms and dwellings of Lochlea and Lochside in the Parish of Tarbolton, South Ayrshire, Scotland. The loch was natural, sitting in a hollow created by glaciation. The loch waters ultimately drained via Fail Loch, the Mill Burn, and the Water of Fail. It is well-documented due to the presence of a crannog that was excavated and documented circa 1878, and its association with the poet Robert Burns, who lived here for several years whilst his father was the tenant. Lochlea lies 2+1⁄2 miles northeast of Tarbolton, and just over three miles northwest of Mauchline.

The 2011–12 Scottish League Cup was the 66th season of Scotland's second-most prestigious football knockout competition, the Scottish League Cup, also known as the Scottish Communities League Cup for sponsorship reasons. It was won by Kilmarnock

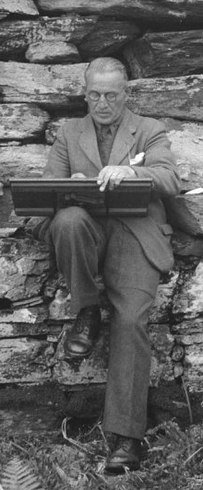

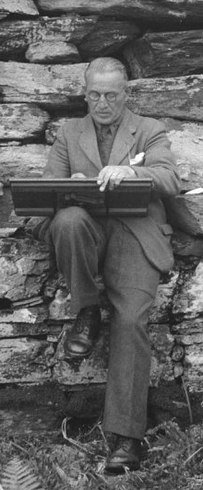

Charles S. T. Calder was a Scottish archaeologist who undertook extensive explorations from the 1920s to 1950s. He is best known for his explorations of Neolithic cairns and buildings in Shetland in the 1940s and 1950s, although his contribution to the investigative work and publications of RCAHMS during a period of over 40 years service cannot be overstated.