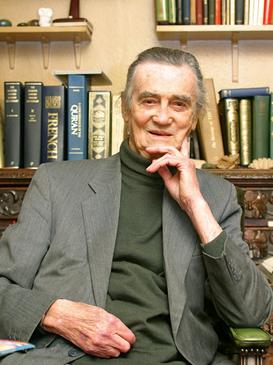

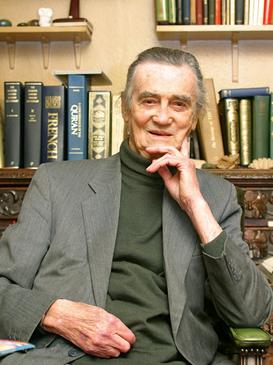

Seyyed Hossein Nasr is an Iranian-American philosopher, theologian and Islamic scholar. He is University Professor of Islamic studies at George Washington University.

The perennial philosophy, also referred to as perennialism and perennial wisdom, is a school of thought in philosophy and spirituality that posits that the recurrence of common themes across world religions illuminates universal truths about the nature of reality, humanity, ethics, and consciousness. Some perennialists emphasize common themes in religious experiences and mystical traditions across time and cultures; others argue that religious traditions share a single metaphysical truth or origin from which all esoteric and exoteric knowledge and doctrine have developed.

Frithjof Schuon was a Swiss metaphysician of German descent, belonging to the Traditionalist School of Perennialism. He was the author of more than twenty works in French on metaphysics, spirituality, religion, anthropology and art, which have been translated into English and many other languages. He was also a painter and a poet.

Traditionalism, also sometimes known as Perennialism, posits the existence of a perennial wisdom or perennial philosophy, primordial and universal truths which form the source for, and are shared by, all the major world religions. Historian Mark Sedgwick identifies René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Julius Evola, Mircea Eliade, Frithjof Schuon, Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Alexandr Dugin to be the seven most prominent Traditionalists.

Hikmah is an Arabic word that means wisdom, sagacity, philosophy, rationale or underlying reason. The Quran mentions "hikmah" in various places, where it is understood as knowledge and understanding of the Quran, fear of God, and a means of nourishing the spirit or intellect. Hikmah is sometimes associated with prophethood, faith, intelligence ('aql), comprehension (fahm), or the power of rational demonstration. In the Quran, God bestows wisdom upon whomever He chooses, and various individuals including the House of Abraham, David, Joseph, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad and Luqman are said to have received wisdom. The Quran also uses the term hikmah in connection with the Book or the scripture in general. The Quran also refers to itself as the Wise Book, and refers to God as The Wise in several places.

William Clark Chittick is an American philosopher, writer, translator, and interpreter of classical Islamic philosophical and mystical texts. He is best known for his work on Rumi and Ibn 'Arabi, and has written extensively on the school of Ibn 'Arabi, Islamic philosophy, and Islamic cosmology. He is a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Asian and Asian American Studies at Stony Brook University.

In Sufism, maʿrifa is the mystical understanding of God or Divine Reality. It has been described as an immediate recognition and understanding of the true nature of things as they are. Ma'rifa encompasses a deep understanding of the ultimate Truth, which is essentially God, and extends to the comprehension of all things in their connection to God. Sufi mystics attain maʿrifa by embarking on a spiritual journey, typically consisting of various stages referred to as "stations" and "states." In the state of ma'rifa, the mystic transcends the temptations of the self and is absorbed in God, experiencing a sense of alienation from their own self.

Peter Kingsley is a mystic, philosopher, and scholar. He is the author of six books and numerous articles, including Ancient Philosophy, Mystery and Magic; In the Dark Places of Wisdom; Reality; A Story Waiting to Pierce You: Mongolia, Tibet and the Destiny of the Western World; Catafalque: Carl Jung and the End of Humanity; and A Book of Life. He has written extensively on the pre-Socratic philosophers Parmenides and Empedocles and the world they lived in.

Charles le Gai Eaton was a British diplomat, writer, historian, and an Islamic scholar. He is perhaps best known for his 1994 book, Islam and the Destiny of Man.

Resacralization is the process of reviving religion or restoring spiritual meanings to various domains of life and thought. It has been termed as the "alter ego" of secularization, which is "a theory claiming that religion loses its holds in modern society". The term rescralization has a variety of connotations in sociology of religion and "very largely draws its meaning" from secularization thesis. According to this viewpoint, religion and spiritual values continue to play an important role in both the private and public realms. Empirical evidence suggests that the world is undergoing a rescralization since religions are gaining ground in contemporary social and political spheres.

Fitra or fitrah is an Arabic word that means 'original disposition', 'natural constitution' or 'innate nature'. The concept somewhat resembles natural order in philosophy, although there are considerable differences as well. In Islam, fitra is the innate human nature that recognizes the oneness of God. It may entail either the state of purity and innocence in which Muslims believe all humans to be born, or the ability to choose or reject God's guidance. The Quran states that humans were created in the most perfect form (95:4), and were endowed with a primordial nature (30:30). Furthermore, God took a covenant from all children of Adam, even before they were sent to Earth's worldly realm, regarding his Lordship (7:172–173). This covenant is considered to have left an everlasting imprint on the human soul, with the Quran emphasizing that on the Day of Judgment no one will be able to plead ignorance of this event (7:172–173).

Illuminationism, also known as Ishrāqiyyun or simply Ishrāqi is a philosophical and mystical school of thought introduced by Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi in the twelfth century, established with his Kitab Hikmat al-Ishraq, a fundamental text finished in 1186. Written with influence from Avicennism, Peripateticism, and Neoplatonism, the philosophy is nevertheless distinct as a novel and holistic addition to the history of Islamic philosophy.

The Matheson Trust is an educational charity based in London dedicated to further and disseminate the study of comparative religion, especially from the point of view of the underlying harmony of the major religious and philosophical traditions of the world.

In traditionalist philosophy, desacralization of knowledge or secularization of knowledge is the process of separation of knowledge from its perceived divine source—God or the Ultimate Reality. The process reflects a paradigm shift in modern conception of knowledge in that it has rejected divine revelations as well as the idea of spiritual and metaphysical foundations of knowledge, confining knowledge to empirical domain and reason alone.

In perennial philosophy, scientia sacra or sacred science is a form of spiritual knowledge that lies at the heart of both divine revelations and traditional sciences, embodying the very essence of every sacred tradition. It recognizes sources of knowledge beyond those accepted by modern epistemology, such as divine revelations and intellectual intuition. Intellectual intuition is believed to allow access to an innate knowledge of God, which is to be reawakened through the use of human intellect. The principles and doctrines of scientia sacra are derived from reason, revelation, and intellectual intuition, with the conviction that these sources of knowledge can be reconciled in a hierarchical order, and applied in the human quest to understand different orders of reality. Its objective is to show how the transmitted, intellectual, and physical sciences are related and unified within the framework of metaphysics, as traditionally defined.

In perennial philosophy, tradition means divinely ordained truths or principles that have been communicated to humanity as well as an entire cosmic sector through various figures such as messengers, prophets, avataras, the Logos, or other transmitting agencies. The purpose of these sacred truths or principles is to continuously remind human beings of the existence of a "Divine Center" and an "Ultimate Origin." According to this perspective, tradition does not refer to custom, habit, or inherited ways of thinking and living. Contrarily, it has a divine foundation and involves the transmission of the sacred message down through the ages. Used in this sense, tradition is synonymous with revelation, and it encompasses all forms of philosophy, art, and culture that are influenced by it.

In traditionalist philosophy, pontifical man is a divine representative who serves as a bridge between heaven and earth. Promethean man, on the other hand, sees himself as an earthly being who has rebelled against God and has no knowledge of his origins or purposes. This concept was notably developed in contemporary language by the Iranian philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

Resacralization of nature is a term used in environmental philosophy to describe the process of restoring the sacred quality of nature. The primary assumption is that nature has a sanctified aspect that has become lost in modern times as a result of the secularization of contemporary worldviews. These secular worldviews are said to be directly responsible for the spiritual crisis in "modern man", which has ultimately resulted in the current environmental degradation. This perspective emphasizes the significance of changing human perceptions of nature through the incorporation of various religious principles and values that connect nature with the divine. The Iranian philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr first conceptualized the theme of resacralization of nature in contemporary language, which was later expounded upon by a number of theologians and philosophers including Alister McGrath, Sallie McFague and Rosemary Radford Ruether.

In traditionalist philosophy, resacralization of knowledge is the reverse of the process of secularization of knowledge. The central premise is that knowledge is intimately connected to its perceived divine source—God or the Ultimate Reality—which has been severed in the modern era. The process of resacralization of knowledge seeks to reinstate the role of intellect—the divine faculty believed to exist in every human being—above and beyond that of reason, as well as to revive the role of traditional metaphysics in acquiring knowledge—especially knowledge of God—by drawing on sacred traditions and sacred science that uphold divine revelations and the spiritual or gnostic teachings of all revealed religions. It aims to restore the primordial connection between God and humanity, which is believed to have been lost. To accomplish this, it relies on the framework of tawhid, which is developed into a comprehensive metaphysical perspective emphasizing the transcendent unity of all phenomena. Iranian philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr elaborated on the process of resacralization of knowledge in his book Knowledge and the Sacred, which was presented as Gifford Lectures in 1981.

The Need for a Sacred Science is a 1993 book by the Iranian philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr.