The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is fluid motion characterized by chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity. It is in contrast to laminar flow, which occurs when a fluid flows in parallel layers with no disruption between those layers.

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces a no-slip boundary condition. The flow velocity then monotonically increases above the surface until it returns to the bulk flow velocity. The thin layer consisting of fluid whose velocity has not yet returned to the bulk flow velocity is called the velocity boundary layer.

A Newtonian fluid is a fluid in which the viscous stresses arising from its flow are at every point linearly correlated to the local strain rate — the rate of change of its deformation over time. Stresses are proportional to the rate of change of the fluid's velocity vector.

Quantum turbulence is the name given to the turbulent flow – the chaotic motion of a fluid at high flow rates – of quantum fluids, such as superfluids. The idea that a form of turbulence might be possible in a superfluid via the quantized vortex lines was first suggested by Richard Feynman. The dynamics of quantum fluids are governed by quantum mechanics, rather than classical physics which govern classical (ordinary) fluids. Some examples of quantum fluids include superfluid helium, Bose–Einstein condensates (BECs), polariton condensates, and nuclear pasta theorized to exist inside neutron stars. Quantum fluids exist at temperatures below the critical temperature at which Bose-Einstein condensation takes place.

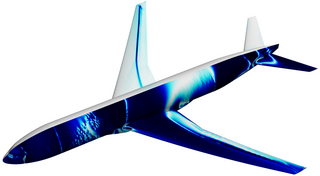

Large eddy simulation (LES) is a mathematical model for turbulence used in computational fluid dynamics. It was initially proposed in 1963 by Joseph Smagorinsky to simulate atmospheric air currents, and first explored by Deardorff (1970). LES is currently applied in a wide variety of engineering applications, including combustion, acoustics, and simulations of the atmospheric boundary layer.

Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids and the forces on them. It has applications in a wide range of disciplines, including mechanical, aerospace, civil, chemical, and biomedical engineering, as well as geophysics, oceanography, meteorology, astrophysics, and biology.

In fluid dynamics, turbulence modeling is the construction and use of a mathematical model to predict the effects of turbulence. Turbulent flows are commonplace in most real-life scenarios. In spite of decades of research, there is no analytical theory to predict the evolution of these turbulent flows. The equations governing turbulent flows can only be solved directly for simple cases of flow. For most real-life turbulent flows, CFD simulations use turbulent models to predict the evolution of turbulence. These turbulence models are simplified constitutive equations that predict the statistical evolution of turbulent flows.

A direct numerical simulation (DNS) is a simulation in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) in which the Navier–Stokes equations are numerically solved without any turbulence model. This means that the whole range of spatial and temporal scales of the turbulence must be resolved. All the spatial scales of the turbulence must be resolved in the computational mesh, from the smallest dissipative scales, up to the integral scale , associated with the motions containing most of the kinetic energy. The Kolmogorov scale, , is given by

In physics and fluid mechanics, a Blasius boundary layer describes the steady two-dimensional laminar boundary layer that forms on a semi-infinite plate which is held parallel to a constant unidirectional flow. Falkner and Skan later generalized Blasius' solution to wedge flow, i.e. flows in which the plate is not parallel to the flow.

In fluid dynamics, turbulence kinetic energy (TKE) is the mean kinetic energy per unit mass associated with eddies in turbulent flow. Physically, the turbulence kinetic energy is characterized by measured root-mean-square (RMS) velocity fluctuations. In the Reynolds-averaged Navier Stokes equations, the turbulence kinetic energy can be calculated based on the closure method, i.e. a turbulence model.

Preferential concentration is the tendency of dense particles in a turbulent fluid to cluster in regions of high strain due to their inertia. The extent by which particles cluster is determined by the Stokes number, defined as , where and are the timescales for the particle and fluid respectively; note that and are the mass densities of the fluid and the particle, respectively, is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, and is the kinetic energy dissipation rate of the turbulence. Maximum preferential concentration occurs at . Particles with follow fluid streamlines and particles with do not respond significantly to the fluid within the times the fluid motions are coherent.

Viscoplasticity is a theory in continuum mechanics that describes the rate-dependent inelastic behavior of solids. Rate-dependence in this context means that the deformation of the material depends on the rate at which loads are applied. The inelastic behavior that is the subject of viscoplasticity is plastic deformation which means that the material undergoes unrecoverable deformations when a load level is reached. Rate-dependent plasticity is important for transient plasticity calculations. The main difference between rate-independent plastic and viscoplastic material models is that the latter exhibit not only permanent deformations after the application of loads but continue to undergo a creep flow as a function of time under the influence of the applied load.

In physics and mathematics, the κ-Poincaré group, named after Henri Poincaré, is a quantum group, obtained by deformation of the Poincaré group into a Hopf algebra. It is generated by the elements and with the usual constraint:

In fluid dynamics, the Taylor microscale, which is sometimes called the turbulence length scale, is a length scale used to characterize a turbulent fluid flow. This microscale is named after Geoffrey Ingram Taylor. The Taylor microscale is the intermediate length scale at which fluid viscosity significantly affects the dynamics of turbulent eddies in the flow. This length scale is traditionally applied to turbulent flow which can be characterized by a Kolmogorov spectrum of velocity fluctuations. In such a flow, length scales which are larger than the Taylor microscale are not strongly affected by viscosity. These larger length scales in the flow are generally referred to as the inertial range. Below the Taylor microscale the turbulent motions are subject to strong viscous forces and kinetic energy is dissipated into heat. These shorter length scale motions are generally termed the dissipation range.

In fluid and molecular dynamics, the Batchelor scale, determined by George Batchelor (1959), describes the size of a droplet of fluid that will diffuse in the same time it takes the energy in an eddy of size η to dissipate. The Batchelor scale can be determined by:

Magnetohydrodynamic turbulence concerns the chaotic regimes of magnetofluid flow at high Reynolds number. Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) deals with what is a quasi-neutral fluid with very high conductivity. The fluid approximation implies that the focus is on macro length-and-time scales which are much larger than the collision length and collision time respectively.

Reynolds stress equation model (RSM), also referred to as second moment closures are the most complete classical turbulence model. In these models, the eddy-viscosity hypothesis is avoided and the individual components of the Reynolds stress tensor are directly computed. These models use the exact Reynolds stress transport equation for their formulation. They account for the directional effects of the Reynolds stresses and the complex interactions in turbulent flows. Reynolds stress models offer significantly better accuracy than eddy-viscosity based turbulence models, while being computationally cheaper than Direct Numerical Simulations (DNS) and Large Eddy Simulations.

In continuum mechanics, an energy cascade involves the transfer of energy from large scales of motion to the small scales or a transfer of energy from the small scales to the large scales. This transfer of energy between different scales requires that the dynamics of the system is nonlinear. Strictly speaking, a cascade requires the energy transfer to be local in scale, evoking a cascading waterfall from pool to pool without long-range transfers across the scale domain.

In fluid dynamics, Rayleigh problem also known as Stokes first problem is a problem of determining the flow created by a sudden movement of an infinitely long plate from rest, named after Lord Rayleigh and Sir George Stokes. This is considered as one of the simplest unsteady problems that have an exact solution for the Navier-Stokes equations. The impulse movement of semi-infinite plate was studied by Keith Stewartson.