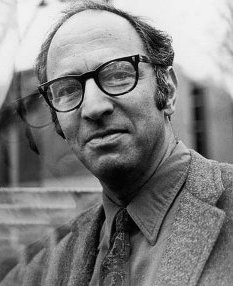

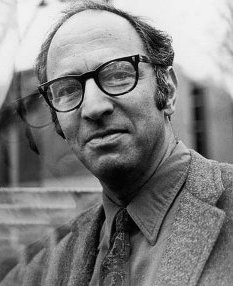

Falsifiability is a deductive standard of evaluation of scientific theories and hypotheses, introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in his book The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934). A theory or hypothesis is falsifiable if it can be logically contradicted by an empirical test.

Sir Karl Raimund Popper was an Austrian–British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the classical inductivist views on the scientific method in favour of empirical falsification. According to Popper, a theory in the empirical sciences can never be proven, but it can be falsified, meaning that it can be scrutinised with decisive experiments. Popper was opposed to the classical justificationist account of knowledge, which he replaced with critical rationalism, namely "the first non-justificational philosophy of criticism in the history of philosophy".

Logical positivism, also known as logical empiricism or neo-positivism, was a philosophical movement, in the empiricist tradition, that sought to formulate a scientific philosophy in which philosophical discourse would be, in the perception of its proponents, as authoritative and meaningful as empirical science.

A paradigm shift is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. It is a concept in the philosophy of science that was introduced and brought into the common lexicon by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn. Even though Kuhn restricted the use of the term to the natural sciences, the concept of a paradigm shift has also been used in numerous non-scientific contexts to describe a profound change in a fundamental model or perception of events.

Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultimate purpose and meaning of science as a human endeavour. Philosophy of science focuses on metaphysical, epistemic and semantic aspects of scientific practice, and overlaps with metaphysics, ontology, logic, and epistemology, for example, when it explores the relationship between science and the concept of truth. Philosophy of science is both a theoretical and empirical discipline, relying on philosophical theorising as well as meta-studies of scientific practice. Ethical issues such as bioethics and scientific misconduct are often considered ethics or science studies rather than the philosophy of science.

Imre Lakatos was a Hungarian philosopher of mathematics and science, known for his thesis of the fallibility of mathematics and its "methodology of proofs and refutations" in its pre-axiomatic stages of development, and also for introducing the concept of the "research programme" in his methodology of scientific research programmes.

In science and philosophy, a paradigm is a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitute legitimate contributions to a field. The word paradigm is Greek in origin, meaning "pattern".

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a book about the history of science by the philosopher Thomas S. Kuhn. Its publication was a landmark event in the history, philosophy, and sociology of science. Kuhn challenged the then prevailing view of progress in science in which scientific progress was viewed as "development-by-accumulation" of accepted facts and theories. Kuhn argued for an episodic model in which periods of conceptual continuity and cumulative progress, referred to as periods of "normal science", were interrupted by periods of revolutionary science. The discovery of "anomalies" accumulating and precipitating revolutions in science leads to new paradigms. New paradigms then ask new questions of old data, move beyond the mere "puzzle-solving" of the previous paradigm, alter the rules of the game and change the "map" directing new research.

Constructivism is a view in the philosophy of science that maintains that scientific knowledge is constructed by the scientific community, which seeks to measure and construct models of the natural world. According to constructivists, natural science consists of mental constructs that aim to explain sensory experiences and measurements, and that there is no single valid methodology in science but rather a diversity of useful methods. They also hold that the world is independent of human minds, but knowledge of the world is always a human and social construction. Constructivism opposes the philosophy of objectivism, embracing the belief that human beings can come to know the truth about the natural world not mediated by scientific approximations with different degrees of validity and accuracy.

Critical rationalism is an epistemological philosophy advanced by Karl Popper on the basis that, if a statement cannot be logically deduced, it might nevertheless be possible to logically falsify it. Following Hume, Popper rejected any inductive logic that is ampliative, i.e., any logic that can provide more knowledge than deductive logic. This led Popper to his falsifiability criterion.

The historiography of science or the historiography of the history of science is the study of the history and methodology of the sub-discipline of history, known as the history of science, including its disciplinary aspects and practices and the study of its own historical development.

In philosophy of science and epistemology, the demarcation problem is the question of how to distinguish between science and non-science. It also examines the boundaries between science, pseudoscience and other products of human activity, like art and literature and beliefs. The debate continues after more than two millennia of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in various fields. The debate has consequences for what can be termed "scientific" in topics such as education and public policy.

Commensurability is a concept in the philosophy of science whereby scientific theories are said to be "commensurable" if scientists can discuss the theories using a shared nomenclature that allows direct comparison of them to determine which one is more valid or useful. On the other hand, theories are incommensurable if they are embedded in starkly contrasting conceptual frameworks whose languages do not overlap sufficiently to permit scientists to directly compare the theories or to cite empirical evidence favoring one theory over the other. Discussed by Ludwik Fleck in the 1930s, and popularized by Thomas Kuhn in the 1960s, the problem of incommensurability results in scientists talking past each other, as it were, while comparison of theories is muddled by confusions about terms, contexts and consequences.

Postpositivism or postempiricism is a metatheoretical stance that critiques and amends positivism and has impacted theories and practices across philosophy, social sciences, and various models of scientific inquiry. While positivists emphasize independence between the researcher and the researched person, postpositivists argue that theories, hypotheses, background knowledge and values of the researcher can influence what is observed. Postpositivists pursue objectivity by recognizing the possible effects of biases. While positivists emphasize quantitative methods, postpositivists consider both quantitative and qualitative methods to be valid approaches.

Philosophy in this sense means how social science integrates with other related scientific disciplines, which implies a rigorous, systematic endeavor to build and organize knowledge relevant to the interaction between individual people and their wider social involvement.

In science, objectivity refers to attempts to do higher quality research by eliminating personal biases, irrational emotions and false beliefs, while focusing mainly on proven facts and evidence. It is often linked to observation as part of the scientific method. It is thus related to the aim of testability and reproducibility. To be considered objective, the results of measurement must be communicated from person to person, and then demonstrated for third parties, as an advance in a collective understanding of the world. Such demonstrable knowledge has ordinarily conferred demonstrable powers of prediction or technology.

Models of scientific inquiry have two functions: first, to provide a descriptive account of how scientific inquiry is carried out in practice, and second, to provide an explanatory account of why scientific inquiry succeeds as well as it appears to do in arriving at genuine knowledge. The philosopher Wesley C. Salmon described scientific inquiry:

The search for scientific knowledge ends far back into antiquity. At some point in the past, at least by the time of Aristotle, philosophers recognized that a fundamental distinction should be drawn between two kinds of scientific knowledge—roughly, knowledge that and knowledge why. It is one thing to know that each planet periodically reverses the direction of its motion with respect to the background of fixed stars; it is quite a different matter to know why. Knowledge of the former type is descriptive; knowledge of the latter type is explanatory. It is explanatory knowledge that provides scientific understanding of the world.

Inductivism is the traditional and still commonplace philosophy of scientific method to develop scientific theories. Inductivism aims to neutrally observe a domain, infer laws from examined cases—hence, inductive reasoning—and thus objectively discover the sole naturally true theory of the observed.

Thomas Samuel Kuhn was an American historian and philosopher of science whose 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was influential in both academic and popular circles, introducing the term paradigm shift, which has since become an English-language idiom.

John William Nevill Watkins was an English philosopher, a professor at the London School of Economics from 1966 until his retirement in 1989 and a prominent proponent of critical rationalism.