A standard form contract is a contract between two parties, where the terms and conditions of the contract are set by one of the parties, and the other party has little or no ability to negotiate more favorable terms and is thus placed in a "take it or leave it" position.

Unconscionability is a doctrine in contract law that describes terms that are so extremely unjust, or overwhelmingly one-sided in favor of the party who has the superior bargaining power, that they are contrary to good conscience. Typically, an unconscionable contract is held to be unenforceable because no reasonable or informed person would otherwise agree to it. The perpetrator of the conduct is not allowed to benefit, because the consideration offered is lacking, or is so obviously inadequate, that to enforce the contract would be unfair to the party seeking to escape the contract.

In contract law, ticket cases are a series of cases that stand for the proposition that if you are handed a ticket or another document with terms, and you retain the ticket or document, then you are bound by those terms. Whether you have read the terms or not is irrelevant, and in a sense, using the ticket is analogous to signing the document. This issue is an important one due to the proliferation of exclusion clauses that accompany tickets in everyday transactions.

Exclusion clauses and limitation clauses are terms in a contract which seek to restrict the rights of the parties to the contract.

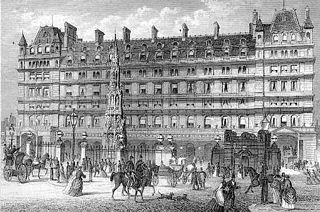

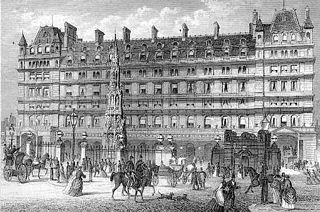

Parker v South Eastern Railway [1877] 2 CPD 416 is a famous English contract law case on exclusion clauses where the court held that an individual cannot escape a contractual term by failing to read the contract but that a party wanting to rely on an exclusion clause must take reasonable steps to bring it to the attention of the customer.

The law of contract in Australia is similar to other Anglo-American common law jurisdictions.

Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corp (England) Ltd [1977] EWCA Civ 9 is a leading English contract law case. It concerns the problem found among some large businesses, with each side attempting to get their preferred standard form agreements to be the basis for a contract.

A Himalaya clause is a contractual provision expressed to be for the benefit of a third party who is not a party to the contract. Although theoretically applicable to any form of contract, most of the jurisprudence relating to Himalaya clauses relate to maritime matters, and exclusion clauses in bills of lading for the benefit of employees, crew, and agents, stevedores in particular.

A contractual term is "any provision forming part of a contract". Each term gives rise to a contractual obligation, the breach of which may give rise to litigation. Not all terms are stated expressly and some terms carry less legal gravity as they are peripheral to the objectives of the contract.

George Mitchell (Chesterhall) Ltd v Finney Lock Seeds Ltd is a case concerning the sale of goods and exclusion clauses. It was decided under the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 and the Sale of Goods Act 1979.

English contract law is the body of law that regulates legally binding agreements in England and Wales. With its roots in the lex mercatoria and the activism of the judiciary during the Industrial Revolution, it shares a heritage with countries across the Commonwealth, from membership in the European Union, continuing membership in Unidroit, and to a lesser extent the United States. Any agreement that is enforceable in court is a contract. A contract is a voluntary obligation, contrasting to the duty to not violate others rights in tort or unjust enrichment. English law places a high value on ensuring people have truly consented to the deals that bind them in court, so long as they comply with statutory and human rights.

A contract is an agreement that specifies certain legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to two or more parties. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to transfer any of those at a future date, and the activities and intentions of the parties entering into a contract may be referred to as contracting. In the event of a breach of contract, the injured party may seek judicial remedies such as damages or equitable remedies such as specific performance or rescission. A binding agreement between actors in international law is known as a treaty.

Contractual terms in English law is a topic which deals with four main issues.

Maredelanto Compania Naviera SA v Bergbau-Handel GmbH or The Mihalis Angelos [1970] EWCA Civ 4 is an English contract law case, concerning breach of contract.

Interpreting contracts in English law is an area of English contract law, which concerns how the courts decide what an agreement means. It is settled law that the process is based on the objective view of a reasonable person, given the context in which the contracting parties made their agreement. This approach marks a break with previous a more rigid modes of interpretation before the 1970s, where courts paid closer attention to the formal expression of the parties' intentions and took more of a literal view of what they had said.

Frederick E Rose (London) Ltd v William H Pim Junior & Co Ltd[1953] 2 QB 450 is an English contract law case concerning the rectification of contractual documents and the interpretation of contracts in English law.

Incorporation of terms in English law is the inclusion of terms in contracts formed under English law in such a way that the courts recognise them as valid. For a term to be considered incorporated it must fulfil three requirements. Firstly, notice of the terms should be given before or during the agreement of the contract. Secondly, the terms must be found in a document intended to be contractual. Thirdly, "reasonable steps" must be taken by the party who forms the term to bring it to the attention of the other party. The rules on incorporating terms in English law are almost all at a common law level.

Autoclenz Ltd v Belcher [2011] UKSC 41 is a landmark UK labour law and English contract law case decided by the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, concerning the scope of statutory protection of rights for working individuals. It confirmed the view, also taken by the Court of Appeal, that the relative bargaining power of the parties must be taken into account when deciding whether a person counts as an employee, to get employment rights. As Lord Clarke said,

the relative bargaining power of the parties must be taken into account in deciding whether the terms of any written agreement in truth represent what was agreed and the true agreement will often have to be gleaned from all the circumstances of the case, of which the written agreement is only a part. This may be described as a purposive approach to the problem.

Rock Advertising Ltd v MWB Business Exchange Centres Ltd[2018] UKSC 24 is a judicial decision of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom relating to contract law, concerning consideration and estoppel. Specifically it concerned the effectiveness of "no oral variation" clauses, which provide that any amendments or waiver in relation to the contract must be in writing.