Related Research Articles

In contract law, ticket cases are a series of cases that stand for the proposition that if you are handed a ticket or another document with terms, and you retain the ticket or document, then you are bound by those terms. Whether you have read the terms or not is irrelevant, and in a sense, using the ticket is analogous to signing the document. This issue is an important one due to the proliferation of exclusion clauses that accompany tickets in everyday transactions.

An exclusion clause is a term in a contract that seeks to restrict the rights of the parties to the contract.

In common law jurisdictions, a misrepresentation is an untrue or misleading statement of fact made during negotiations by one party to another, the statement then inducing that other party to enter into a contract. The misled party may normally rescind the contract, and sometimes may be awarded damages as well.

Parker v South Eastern Railway [1877] 2 CPD 416 is a famous English contract law case on exclusion clauses where the court held that an individual cannot escape a contractual term by failing to read the contract but that a party wanting to rely on an exclusion clause must take reasonable steps to bring it to the attention of the customer.

Loss of chance in English law refers to a particular problem of causation, which arises in tort and contract. The law is invited to assess hypothetical outcomes, either affecting the claimant or a third party, where the defendant's breach of contract or of the duty of care for the purposes of negligence deprived the claimant of the opportunity to obtain a benefit and/or avoid a loss. For these purposes, the remedy of damages is normally intended to compensate for the claimant's loss of expectation. The general rule is that while a loss of chance is compensable when the chance was something promised on a contract it is not generally so in the law of tort, where most cases thus far have been concerned with medical negligence in the public health system.

The law of contract in Australia is similar to other Anglo-American common law jurisdictions.

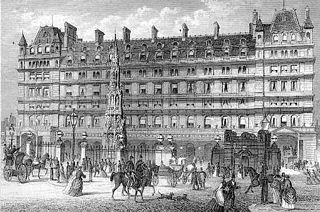

Olley v Marlborough Court Hotel[1949] 1 KB 532 is an English contract law case on exclusion clauses in contract law. The case stood for the proposition that a representation made by one party cannot become a term of a contract if made after the agreement was made. The representation can only be binding where it was made at the time the contract was formed.

English contract law is the body of law that regulates legally binding agreements in England and Wales. With its roots in the lex mercatoria and the activism of the judiciary during the industrial revolution, it shares a heritage with countries across the Commonwealth, from membership in the European Union, continuing membership in Unidroit, and to a lesser extent the United States. Any agreement that is enforceable in court is a contract. A contract is a voluntary obligation, contrasting to the duty to not violate others rights in tort or unjust enrichment. English law places a high value on ensuring people have truly consented to the deals that bind them in court, so long as they comply with statutory and human rights.

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations among its parties. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to transfer any of those at a future date. In the event of a breach of contract, the injured party may seek judicial remedies such as damages or rescission. Contract law, the field of the law of obligations concerned with contracts, is based on the principle that agreements must be honoured.

Contractual terms in English law is a topic which deals with four main issues.

Interpreting contracts in English law is an area of English contract law, which concerns how the courts decide what an agreement means. It is settled law that the process is based on the objective view of a reasonable person, given the context in which the contracting parties made their agreement. This approach marks a break with previous a more rigid modes of interpretation before the 1970s, where courts paid closer attention to the formal expression of the parties' intentions and took more of a literal view of what they had said.

Intention to create legal relations', otherwise an "intention to be legally bound", is a doctrine used in contract law, particularly English contract law and related common law jurisdictions.

Privity is a doctrine in English contract law that covers the relationship between parties to a contract and other parties or agents. At its most basic level, the rule is that a contract can neither give rights to, nor impose obligations on, anyone who is not a party to the original agreement, i.e. a "third party". Historically, third parties could enforce the terms of a contract, as evidenced in Provender v Wood, but the law changed in a series of cases in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the most well known of which are Tweddle v Atkinson in 1861 and Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre v Selfridge and Co Ltd in 1915.

The Contracts Act 1999 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly reformed the common law doctrine of privity and "thereby [removed] one of the most universally disliked and criticised blots on the legal landscape". The second rule of the Doctrine of Privity, that a third party could not enforce a contract for which he had not provided consideration, had been widely criticised by lawyers, academics and members of the judiciary. Proposals for reform via an act of Parliament were first made in 1937 by the Law Revision Committee in their Sixth Interim Report. No further action was taken by the government until the 1990s, when the Law Commission proposed a new draft bill in 1991, and presented their final report in 1996. The bill was introduced to the House of Lords in December 1998, and moved to the House of Commons on 14 June 1999. It received the Royal Assent on 11 November 1999, coming into force immediately as the Contracts Act 1999.

Capacity in English law refers to the ability of a contracting party to enter into legally binding relations. If a party does not have the capacity to do so, then subsequent contracts may be invalid; however, in the interests of certainty, there is a prima facie presumption that both parties hold the capacity to contract. Those who contract without a full knowledge of the relevant subject matter, or those who are illiterate or unfamiliar with the English language, will not often be released from their bargains.

McCutcheon v David MacBrayne Ltd [1964] 1 WLR 125 is a Scottish contract law case, concerning the incorporation of a term through a course of dealings.

Autoclenz Ltd v Belcher [2011] UKSC 41 is a landmark UK labour law and English contract law case decided by the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, concerning the scope of statutory protection of rights for working individuals. It confirmed the view, also taken by the Court of Appeal, that the relative bargaining power of the parties must be taken into account when deciding whether a person counts as an employee, to get employment rights. As Lord Clarke said,

the relative bargaining power of the parties must be taken into account in deciding whether the terms of any written agreement in truth represent what was agreed and the true agreement will often have to be gleaned from all the circumstances of the case, of which the written agreement is only a part. This may be described as a purposive approach to the problem.

Unfair terms in English contract law are regulated under three major pieces of legislation, compliance with which is enforced by the Office of Fair Trading. The Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 is the first main Act, which covers some contracts that have exclusion and limitation clauses. For example, it will not extend to cover contracts which are mentioned in Schedule I, consumer contracts, and international supply contracts. The Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 partially lays on top further requirements for consumer contracts. The Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 concerns certain sales practices.

South African contract law is "essentially a modernized version of the Roman-Dutch law of contract", and is rooted in canon and Roman laws. In the broadest definition, a contract is an agreement two or more parties enter into with the serious intention of creating a legal obligation. Contract law provides a legal framework within which persons can transact business and exchange resources, secure in the knowledge that the law will uphold their agreements and, if necessary, enforce them. The law of contract underpins private enterprise in South Africa and regulates it in the interest of fair dealing.

Cavendish Square Holding BV v Talal El Makdessi[2015] UKSC 67, together with its companion case ParkingEye Ltd v Beavis, are English contract law cases concerning the validity of penalty clauses and the application of the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Directive.

References

- 1 2 3 McKendrick (2007) p.191

- 1 2 3 Peel (2007) p.243

- ↑ Furmston (2007) p.205

- ↑ Turner (2007) p.169

- ↑ McKendrick (2007) p.194

- ↑ Turner (2007) p.171

- 1 2 Peel (2007) p.241

- ↑ Turner (2007) p.168

- ↑ McKendrick (2007) p.186

- ↑ see also Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52 , (2004) 219 CLR 165(11 November 2004), High Court (Australia).

- 1 2 McKendrick (2007) p.192

- ↑ Turner (2007) p.173