Related Research Articles

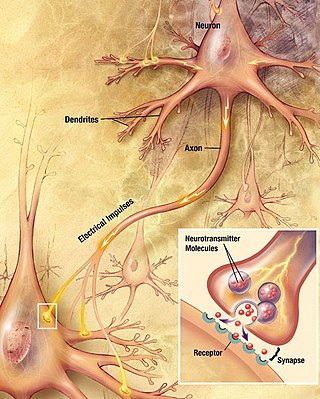

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous system. They are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They allow the nervous system to connect to and control other systems of the body.

The α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor is an ionotropic transmembrane receptor for glutamate (iGluR) that mediates fast synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (CNS). It has been traditionally classified as a non-NMDA-type receptor, along with the kainate receptor. Its name is derived from its ability to be activated by the artificial glutamate analog AMPA. The receptor was first named the "quisqualate receptor" by Watkins and colleagues after a naturally occurring agonist quisqualate and was only later given the label "AMPA receptor" after the selective agonist developed by Tage Honore and colleagues at the Royal Danish School of Pharmacy in Copenhagen. The GRIA2-encoded AMPA receptor ligand binding core was the first glutamate receptor ion channel domain to be crystallized.

In neuroscience, synaptic plasticity is the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time, in response to increases or decreases in their activity. Since memories are postulated to be represented by vastly interconnected neural circuits in the brain, synaptic plasticity is one of the important neurochemical foundations of learning and memory.

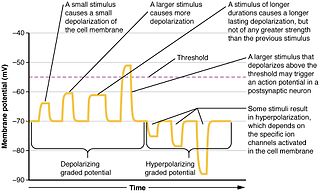

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a kind of synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron less likely to generate an action potential. IPSP were first investigated in motorneurons by David P. C. Lloyd, John Eccles and Rodolfo Llinás in the 1950s and 1960s. The opposite of an inhibitory postsynaptic potential is an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), which is a synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron more likely to generate an action potential. IPSPs can take place at all chemical synapses, which use the secretion of neurotransmitters to create cell to cell signalling. Inhibitory presynaptic neurons release neurotransmitters that then bind to the postsynaptic receptors; this induces a change in the permeability of the postsynaptic neuronal membrane to particular ions. An electric current that changes the postsynaptic membrane potential to create a more negative postsynaptic potential is generated, i.e. the postsynaptic membrane potential becomes more negative than the resting membrane potential, and this is called hyperpolarisation. To generate an action potential, the postsynaptic membrane must depolarize—the membrane potential must reach a voltage threshold more positive than the resting membrane potential. Therefore, hyperpolarisation of the postsynaptic membrane makes it less likely for depolarisation to sufficiently occur to generate an action potential in the postsynaptic neurone.

In neuroscience, an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) is a postsynaptic potential that makes the postsynaptic neuron more likely to fire an action potential. This temporary depolarization of postsynaptic membrane potential, caused by the flow of positively charged ions into the postsynaptic cell, is a result of opening ligand-gated ion channels. These are the opposite of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), which usually result from the flow of negative ions into the cell or positive ions out of the cell. EPSPs can also result from a decrease in outgoing positive charges, while IPSPs are sometimes caused by an increase in positive charge outflow. The flow of ions that causes an EPSP is an excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC).

In neurophysiology, long-term depression (LTD) is an activity-dependent reduction in the efficacy of neuronal synapses lasting hours or longer following a long patterned stimulus. LTD occurs in many areas of the CNS with varying mechanisms depending upon brain region and developmental progress.

In neuroscience, a silent synapse is an excitatory glutamatergic synapse whose postsynaptic membrane contains NMDA-type glutamate receptors but no AMPA-type glutamate receptors. These synapses are named "silent" because normal AMPA receptor-mediated signaling is not present, rendering the synapse inactive under typical conditions. Silent synapses are typically considered to be immature glutamatergic synapses. As the brain matures, the relative number of silent synapses decreases. However, recent research on hippocampal silent synapses shows that while they may indeed be a developmental landmark in the formation of a synapse, that synapses can be "silenced" by activity, even once they have acquired AMPA receptors. Thus, silence may be a state that synapses can visit many times during their lifetimes.

Graded potentials are changes in membrane potential that vary in size, as opposed to being all-or-none. They include diverse potentials such as receptor potentials, electrotonic potentials, subthreshold membrane potential oscillations, slow-wave potential, pacemaker potentials, and synaptic potentials, which scale with the magnitude of the stimulus. They arise from the summation of the individual actions of ligand-gated ion channel proteins, and decrease over time and space. They do not typically involve voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels. These impulses are incremental and may be excitatory or inhibitory. They occur at the postsynaptic dendrite in response to presynaptic neuron firing and release of neurotransmitter, or may occur in skeletal, smooth, or cardiac muscle in response to nerve input. The magnitude of a graded potential is determined by the strength of the stimulus.

An excitatory synapse is a synapse in which an action potential in a presynaptic neuron increases the probability of an action potential occurring in a postsynaptic cell. Neurons form networks through which nerve impulses travel, each neuron often making numerous connections with other cells. These electrical signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, and, if the total of excitatory influences exceeds that of the inhibitory influences, the neuron will generate a new action potential at its axon hillock, thus transmitting the information to yet another cell.

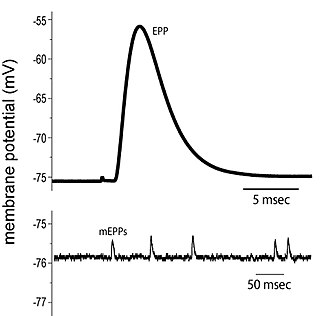

End plate potentials (EPPs) are the voltages which cause depolarization of skeletal muscle fibers caused by neurotransmitters binding to the postsynaptic membrane in the neuromuscular junction. They are called "end plates" because the postsynaptic terminals of muscle fibers have a large, saucer-like appearance. When an action potential reaches the axon terminal of a motor neuron, vesicles carrying neurotransmitters are exocytosed and the contents are released into the neuromuscular junction. These neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane and lead to its depolarization. In the absence of an action potential, acetylcholine vesicles spontaneously leak into the neuromuscular junction and cause very small depolarizations in the postsynaptic membrane. This small response (~0.4mV) is called a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) and is generated by one acetylcholine-containing vesicle. It represents the smallest possible depolarization which can be induced in a muscle.

Postsynaptic potentials are changes in the membrane potential of the postsynaptic terminal of a chemical synapse. Postsynaptic potentials are graded potentials, and should not be confused with action potentials although their function is to initiate or inhibit action potentials. They are caused by the presynaptic neuron releasing neurotransmitters from the terminal bouton at the end of an axon into the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic terminal, which may be a neuron or a muscle cell in the case of a neuromuscular junction. These are collectively referred to as postsynaptic receptors, since they are on the membrane of the postsynaptic cell.

Schaffer collaterals are axon collaterals given off by CA3 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus. These collaterals project to area CA1 of the hippocampus and are an integral part of memory formation and the emotional network of the Papez circuit, and of the hippocampal trisynaptic loop. It is one of the most studied synapses in the world and named after the Hungarian anatomist-neurologist Károly Schaffer.

Metaplasticity is a term originally coined by W.C. Abraham and M.F. Bear to refer to the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Until that time synaptic plasticity had referred to the plastic nature of individual synapses. However this new form referred to the plasticity of the plasticity itself, thus the term meta-plasticity. The idea is that the synapse's previous history of activity determines its current plasticity. This may play a role in some of the underlying mechanisms thought to be important in memory and learning such as long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD) and so forth. These mechanisms depend on current synaptic "state", as set by ongoing extrinsic influences such as the level of synaptic inhibition, the activity of modulatory afferents such as catecholamines, and the pool of hormones affecting the synapses under study. Recently, it has become clear that the prior history of synaptic activity is an additional variable that influences the synaptic state, and thereby the degree, of LTP or LTD produced by a given experimental protocol. In a sense, then, synaptic plasticity is governed by an activity-dependent plasticity of the synaptic state; such plasticity of synaptic plasticity has been termed metaplasticity. There is little known about metaplasticity, and there is much research currently underway on the subject, despite its difficulty of study, because of its theoretical importance in brain and cognitive science. Most research of this type is done via cultured hippocampus cells or hippocampal slices.

Synaptic potential refers to the potential difference across the postsynaptic membrane that results from the action of neurotransmitters at a neuronal synapse. In other words, it is the “incoming” signal that a neuron receives. There are two forms of synaptic potential: excitatory and inhibitory. The type of potential produced depends on both the postsynaptic receptor, more specifically the changes in conductance of ion channels in the post synaptic membrane, and the nature of the released neurotransmitter. Excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) depolarize the membrane and move the potential closer to the threshold for an action potential to be generated. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) hyperpolarize the membrane and move the potential farther away from the threshold, decreasing the likelihood of an action potential occurring. The Excitatory Post Synaptic potential is most likely going to be carried out by the neurotransmitters glutamate and acetylcholine, while the Inhibitory post synaptic potential will most likely be carried out by the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. In order to depolarize a neuron enough to cause an action potential, there must be enough EPSPs to both depolarize the postsynaptic membrane from its resting membrane potential to its threshold and counterbalance the concurrent IPSPs that hyperpolarize the membrane. As an example, consider a neuron with a resting membrane potential of -70 mV (millivolts) and a threshold of -50 mV. It will need to be raised 20 mV in order to pass the threshold and fire an action potential. The neuron will account for all the many incoming excitatory and inhibitory signals via summative neural integration, and if the result is an increase of 20 mV or more, an action potential will occur.

Neural backpropagation is the phenomenon in which, after the action potential of a neuron creates a voltage spike down the axon, another impulse is generated from the soma and propagates towards the apical portions of the dendritic arbor or dendrites. In addition to active backpropagation of the action potential, there is also passive electrotonic spread. While there is ample evidence to prove the existence of backpropagating action potentials, the function of such action potentials and the extent to which they invade the most distal dendrites remain highly controversial.

Summation, which includes both spatial summation and temporal summation, is the process that determines whether or not an action potential will be generated by the combined effects of excitatory and inhibitory signals, both from multiple simultaneous inputs, and from repeated inputs. Depending on the sum total of many individual inputs, summation may or may not reach the threshold voltage to trigger an action potential.

Cellular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience concerned with the study of neurons at a cellular level. This includes morphology and physiological properties of single neurons. Several techniques such as intracellular recording, patch-clamp, and voltage-clamp technique, pharmacology, confocal imaging, molecular biology, two photon laser scanning microscopy and Ca2+ imaging have been used to study activity at the cellular level. Cellular neuroscience examines the various types of neurons, the functions of different neurons, the influence of neurons upon each other, and how neurons work together.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.

Homosynaptic plasticity is one type of synaptic plasticity. Homosynaptic plasticity is input-specific, meaning changes in synapse strength occur only at post-synaptic targets specifically stimulated by a pre-synaptic target. Therefore, the spread of the signal from the pre-synaptic cell is localized.

Neurotransmitters are released into a synapse in packaged vesicles called quanta. One quantum generates what is known as a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) which is the smallest amount of stimulation that one neuron can send to another neuron. Quantal release is the mechanism by which most traditional endogenous neurotransmitters are transmitted throughout the body. The aggregate sum of many MEPPs is known as an end plate potential (EPP). A normal end plate potential usually causes the postsynaptic neuron to reach its threshold of excitation and elicit an action potential. Electrical synapses do not use quantal neurotransmitter release and instead use gap junctions between neurons to send current flows between neurons. The goal of any synapse is to produce either an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) or an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP), which generate or repress the expression, respectively, of an action potential in the postsynaptic neuron. It is estimated that an action potential will trigger the release of approximately 20% of an axon terminal's neurotransmitter load.

References

- ↑ Siegelbaum, Steven A.; Kandel, Eric R. (1991-06-01). "Learning-related synaptic plasticity: LTP and LTD". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1 (1): 113–120. doi:10.1016/0959-4388(91)90018-3. PMID 1822291. S2CID 27798921.

- ↑ Bliss, T. V. P.; Lømo, T. (1973-07-01). "Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path". The Journal of Physiology. 232 (2): 331–356. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. ISSN 1469-7793. PMC 1350458 . PMID 4727084.

- ↑ Enabera I. Flatman JA. Lambert JDC (1979). "The actions of excitatory amino acids on motomeurones in the feline spinal cord". Journal of Physiology. 288: 227–261. PMC 1281424 . PMID 224166.