A eutectic system or eutectic mixture is a homogeneous mixture that has a melting point lower than those of the constituents. The lowest possible melting point over all of the mixing ratios of the constituents is called the eutectic temperature. On a phase diagram, the eutectic temperature is seen as the eutectic point.

Heat treating is a group of industrial, thermal and metalworking processes used to alter the physical, and sometimes chemical, properties of a material. The most common application is metallurgical. Heat treatments are also used in the manufacture of many other materials, such as glass. Heat treatment involves the use of heating or chilling, normally to extreme temperatures, to achieve the desired result such as hardening or softening of a material. Heat treatment techniques include annealing, case hardening, precipitation strengthening, tempering, carburizing, normalizing and quenching. Although the term heat treatment applies only to processes where the heating and cooling are done for the specific purpose of altering properties intentionally, heating and cooling often occur incidentally during other manufacturing processes such as hot forming or welding.

Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. By analogy the term can also refer to any crystal structure that is formed by diffusionless transformation.

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a metallic, non-magnetic allotrope of iron or a solid solution of iron with an alloying element. In plain-carbon steel, austenite exists above the critical eutectoid temperature of 1000 K (727 °C); other alloys of steel have different eutectoid temperatures. The austenite allotrope is named after Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen (1843–1902). It exists at room temperature in some stainless steels due to the presence of nickel stabilizing the austenite at lower temperatures.

Bainite is a plate-like microstructure that forms in steels at temperatures of 125–550 °C. First described by E. S. Davenport and Edgar Bain, it is one of the products that may form when austenite is cooled past a temperature where it is no longer thermodynamically stable with respect to ferrite, cementite, or ferrite and cementite. Davenport and Bain originally described the microstructure as being similar in appearance to tempered martensite.

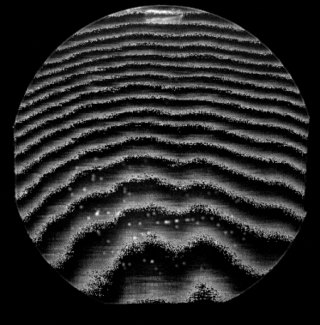

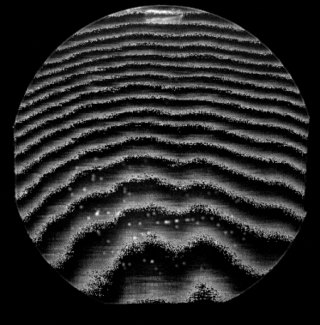

Pearlite is a two-phased, lamellar structure composed of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite that occurs in some steels and cast irons. During slow cooling of an iron-carbon alloy, pearlite forms by a eutectoid reaction as austenite cools below 723 °C (1,333 °F). Pearlite is a microstructure occurring in many common grades of steels.

Aluminium–silicon alloys or Silumin is a general name for a group of lightweight, high-strength aluminium alloys based on an aluminum–silicon system (AlSi) that consist predominantly of aluminum - with silicon as the quantitatively most important alloying element. Pure AlSi alloys cannot be hardened, the commonly used alloys AlSiCu and AlSiMg can be hardened. The hardening mechanism corresponds to that of AlCu and AlMgSi.

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, gas, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such as phase transformations, from occurring. It does this by reducing the window of time during which these undesired reactions are both thermodynamically favorable and kinetically accessible; for instance, quenching can reduce the crystal grain size of both metallic and plastic materials, increasing their hardness.

Widmanstätten patterns, also known as Thomson structures, are figures of long phases of nickel–iron, found in the octahedrite shapes of iron meteorite crystals and some pallasites.

A lamella is a small plate or flake, from the Latin, and may also be used to refer to collections of fine sheets of material held adjacent to one another, in a gill-shaped structure, often with fluid in between though sometimes simply a set of 'welded' plates. The term is used in biological contexts to describe thin membranes of plates of tissue. In context of materials science, the microscopic structures in bone and nacre are called lamellae. Moreover, the term lamella is often used as a way to describe crystal structure of some materials.

Sanidine is the high temperature form of potassium feldspar with a general formula K(AlSi3O8). Sanidine is found most typically in felsic volcanic rocks such as obsidian, rhyolite and trachyte. Sanidine crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system. Orthoclase is a monoclinic polymorph stable at lower temperatures. At yet lower temperatures, microcline, a triclinic polymorph of potassium feldspar, is stable.

A solid solution, a term popularly used for metals, is a homogeneous mixture of two different kinds of atoms in solid state and having a single crystal structure. Many examples can be found in metallurgy, geology, and solid-state chemistry. The word "solution" is used to describe the intimate mixing of components at the atomic level and distinguishes these homogeneous materials from physical mixtures of components. Two terms are mainly associated with solid solutions – solvents and solutes, depending on the relative abundance of the atomic species.

In metallurgy and materials science, annealing is a heat treatment that alters the physical and sometimes chemical properties of a material to increase its ductility and reduce its hardness, making it more workable. It involves heating a material above its recrystallization temperature, maintaining a suitable temperature for an appropriate amount of time and then cooling.

A lamella in biology refers to a thin layer, membrane or plate of tissue. This is a very broad definition, and can refer to many different structures. Any thin layer of organic tissue can be called a lamella and there is a wide array of functions an individual layer can serve. For example, an intercellular lipid lamella is formed when lamellar disks fuse to form a lamellar sheet. It is believed that these disks are formed from vesicles, giving the lamellar sheet a lipid bilayer that plays a role in water diffusion.

In iron and steel metallurgy, ledeburite is a mixture of 4.3% carbon in iron and is a eutectic mixture of austenite and cementite. Ledeburite is not a type of steel as the carbon level is too high although it may occur as a separate constituent in some high carbon steels. It is mostly found with cementite or pearlite in a range of cast irons.

A symplectite is a material texture: a micrometre-scale or submicrometre-scale intergrowth of two or more crystals. Symplectites form from the breakdown of unstable phases, and may be composed of minerals, ceramics, or metals. Fundamentally, their formation is the result of slow grain-boundary diffusion relative to interface propagation rate.

Eutectic bonding, also referred to as eutectic soldering, describes a wafer bonding technique with an intermediate metal layer that can produce a eutectic system. Those eutectic metals are alloys that transform directly from solid to liquid state, or vice versa from liquid to solid state, at a specific composition and temperature without passing a two-phase equilibrium, i.e. liquid and solid state. The fact that the eutectic temperature can be much lower than the melting temperature of the two or more pure elements can be important in eutectic bonding.

Transient liquid phase diffusion bonding (TLPDB) is a joining process that has been applied for bonding many metallic and ceramic systems which cannot be bonded by conventional fusion welding techniques. The bonding process produces joints with a uniform composition profile, tolerant of surface oxides and geometrical defects. The bonding technique has been exploited in a wide range of applications, from the production and repair of turbine engines in the aerospace industry, to nuclear power plants, and in making connections to integrated circuit dies as a part of the microelectronics industry.

The elements bismuth and indium have relatively low melting points when compared to other metals, and their alloy bismuth–indium (Bi–In) is classified as a fusible alloy. It has a melting point lower than the eutectic point of the tin–lead alloy. The most common application of the Bi-In alloy is as a low temperature solder, which can also contain, besides bismuth and indium, lead, cadmium, and tin.