Related Research Articles

A saccade is a quick, simultaneous movement of both eyes between two or more phases of fixation in the same direction. In contrast, in smooth pursuit movements, the eyes move smoothly instead of in jumps. The phenomenon can be associated with a shift in frequency of an emitted signal or a movement of a body part or device. Controlled cortically by the frontal eye fields (FEF), or subcortically by the superior colliculus, saccades serve as a mechanism for fixation, rapid eye movement, and the fast phase of optokinetic nystagmus. The word appears to have been coined in the 1880s by French ophthalmologist Émile Javal, who used a mirror on one side of a page to observe eye movement in silent reading, and found that it involves a succession of discontinuous individual movements.

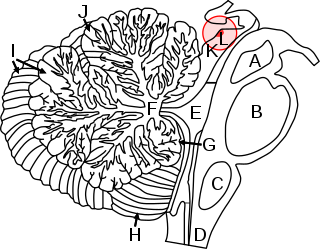

The visual system comprises the sensory organ and parts of the central nervous system which gives organisms the sense of sight as well as enabling the formation of several non-image photo response functions. It detects and interprets information from the optical spectrum perceptible to that species to "build a representation" of the surrounding environment. The visual system carries out a number of complex tasks, including the reception of light and the formation of monocular neural representations, colour vision, the neural mechanisms underlying stereopsis and assessment of distances to and between objects, the identification of a particular object of interest, motion perception, the analysis and integration of visual information, pattern recognition, accurate motor coordination under visual guidance, and more. The neuropsychological side of visual information processing is known as visual perception, an abnormality of which is called visual impairment, and a complete absence of which is called blindness. Non-image forming visual functions, independent of visual perception, include the pupillary light reflex and circadian photoentrainment.

The parietal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The parietal lobe is positioned above the temporal lobe and behind the frontal lobe and central sulcus.

In neuroanatomy, the superior colliculus is a structure lying on the roof of the mammalian midbrain. In non-mammalian vertebrates, the homologous structure is known as the optic tectum, or optic lobe. The adjective form tectal is commonly used for both structures.

Microsaccades are a kind of fixational eye movement. They are small, jerk-like, involuntary eye movements, similar to miniature versions of voluntary saccades. They typically occur during prolonged visual fixation, not only in humans, but also in animals with foveal vision. Microsaccade amplitudes vary from 2 to 120 arcminutes. The first empirical evidence for their existence was provided by Robert Darwin, the father of Charles Darwin.

In the scientific study of vision, smooth pursuit describes a type of eye movement in which the eyes remain fixated on a moving object. It is one of two ways that visual animals can voluntarily shift gaze, the other being saccadic eye movements. Pursuit differs from the vestibulo-ocular reflex, which only occurs during movements of the head and serves to stabilize gaze on a stationary object. Most people are unable to initiate pursuit without a moving visual signal. The pursuit of targets moving with velocities of greater than 30°/s tends to require catch-up saccades. Smooth pursuit is asymmetric: most humans and primates tend to be better at horizontal than vertical smooth pursuit, as defined by their ability to pursue smoothly without making catch-up saccades. Most humans are also better at downward than upward pursuit. Pursuit is modified by ongoing visual feedback.

The frontal eye fields (FEF) are a region located in the frontal cortex, more specifically in Brodmann area 8 or BA8, of the primate brain. In humans, it can be more accurately said to lie in a region around the intersection of the middle frontal gyrus with the precentral gyrus, consisting of a frontal and parietal portion. The FEF is responsible for saccadic eye movements for the purpose of visual field perception and awareness, as well as for voluntary eye movement. The FEF communicates with extraocular muscles indirectly via the paramedian pontine reticular formation. Destruction of the FEF causes deviation of the eyes to the ipsilateral side.

Supplementary eye field (SEF) is the name for the anatomical area of the dorsal medial frontal lobe of the primate cerebral cortex that is indirectly involved in the control of saccadic eye movements. Evidence for a supplementary eye field was first shown by Schlag, and Schlag-Rey. Current research strives to explore the SEF's contribution to visual search and its role in visual salience. The SEF constitutes together with the frontal eye fields (FEF), the intraparietal sulcus (IPS), and the superior colliculus (SC) one of the most important brain areas involved in the generation and control of eye movements, particularly in the direction contralateral to their location. Its precise function is not yet fully known. Neural recordings in the SEF show signals related to both vision and saccades somewhat like the frontal eye fields and superior colliculus, but currently most investigators think that the SEF has a special role in high level aspects of saccade control, like complex spatial transformations, learned transformations, and executive cognitive functions.

The intraparietal sulcus (IPS) is located on the lateral surface of the parietal lobe, and consists of an oblique and a horizontal portion. The IPS contains a series of functionally distinct subregions that have been intensively investigated using both single cell neurophysiology in primates and human functional neuroimaging. Its principal functions are related to perceptual-motor coordination and visual attention, which allows for visually-guided pointing, grasping, and object manipulation that can produce a desired effect.

Attentional shift occurs when directing attention to a point increases the efficiency of processing of that point and includes inhibition to decrease attentional resources to unwanted or irrelevant inputs. Shifting of attention is needed to allocate attentional resources to more efficiently process information from a stimulus. Research has shown that when an object or area is attended, processing operates more efficiently. Task switching costs occur when performance on a task suffers due to the increased effort added in shifting attention. There are competing theories that attempt to explain why and how attention is shifted as well as how attention is moved through space.

The posterior parietal cortex plays an important role in planned movements, spatial reasoning, and attention.

Eye–hand coordination is the coordinated motor control of eye movement with hand movement and the processing of visual input to guide reaching and grasping along with the use of proprioception of the hands to guide the eyes, a modality of multisensory integration. Eye–hand coordination has been studied in activities as diverse as the movement of solid objects such as wooden blocks, archery, sporting performance, music reading, computer gaming, copy-typing, and even tea-making. It is part of the mechanisms of performing everyday tasks; in its absence, most people would be unable to carry out even the simplest of actions such as picking up a book from a table.

Richard Alan Andersen is an American neuroscientist. He is the James G. Boswell Professor of Neuroscience at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. His research focuses on visual physiology with an emphasis on translational research to humans in the field of neuroprosthetics, brain-computer interfaces, and cortical repair.

Chronostasis is a type of temporal illusion in which the first impression following the introduction of a new event or task-demand to the brain can appear to be extended in time. For example, chronostasis temporarily occurs when fixating on a target stimulus, immediately following a saccade. This elicits an overestimation in the temporal duration for which that target stimulus was perceived. This effect can extend apparent durations by up to half a second and is consistent with the idea that the visual system models events prior to perception.

Transsaccadic memory is the neural process that allows humans to perceive their surroundings as a seamless, unified image despite rapid changes in fixation points. Transsaccadic memory is a relatively new topic of interest in the field of psychology. Conflicting views and theories have spurred several types of experiments intended to explain transsaccadic memory and the neural mechanisms involved.

Gain field encoding is a hypothesis about the internal storage and processing of limb motion in the brain. In the motor areas of the brain, there are neurons which collectively have the ability to store information regarding both limb positioning and velocity in relation to both the body (intrinsic) and the individual's external environment (extrinsic). The input from these neurons is taken multiplicatively, forming what is referred to as a gain field. The gain field works as a collection of internal models off of which the body can base its movements. The process of encoding and recalling these models is the basis of muscle memory.

The anti-saccade (AS) task is a gross estimation of injury or dysfunction of the frontal lobe, by assessing the brain’s ability to inhibit the reflexive saccade. Saccadic eye movement is primarily controlled by the frontal cortex.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

Peter H. Schiller is a professor emeritus of Neuroscience in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is well known for his work on the behavioral, neurophysiological and pharmacological studies of the primate visual and oculomotor systems.

Michael E. Goldberg, also known as Mickey Goldberg, is an American neuroscientist and David Mahoney Professor at Columbia University. He is known for his work on the mechanisms of the mammalian eye in relation to brain activity. He served as president of the Society for Neuroscience from 2009 to 2010.

References

- ↑ Bear, Mark, Barry Connors, and Michael Paradiso. (2002). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 757–758.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gnadt, J. W., & Andersen, R. A. (1988). Memory related motor planning activity in posterior parietal cortex of macaque. Experimental Brain Research, 70(1), 216-220.

- ↑ Pesaran, B., Pezaris, J. S., Sahani, M., Mitra, P. P., & Andersen, R. A. (2002). Temporal structure in neuronal activity during working memory in macaque parietal cortex. Nature neuroscience, 5(8), 805-811.

- ↑ Platt, Michael L.; Paul W. Glimcher (1999-07-15). "Neural correlates of decision variables in parietal cortex". Nature. 400 (6741): 233–238. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..233P. doi:10.1038/22268. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10421364. S2CID 4389701.