Related Research Articles

Common law is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions.

Lesotho, formally the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. As an enclave of South Africa, with which it shares a 1,106 km (687 mi) border, it is the largest sovereign enclave in the world, and the only one outside of the Italian Peninsula. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the highest peak in Southern Africa. It has an area of over 30,000 km2 (11,600 sq mi) and has a population of about two million. Its capital and largest city is Maseru. The country is also known by the nickname The Mountain Kingdom.

The legal system of Canada is pluralist: its foundations lie in the English common law system, the French civil law system, and Indigenous law systems developed by the various Indigenous Nations.

The legal system of Australia has multiple forms. It includes a written constitution, unwritten constitutional conventions, statutes, regulations, and the judicially determined common law system. Its legal institutions and traditions are substantially derived from that of the English legal system, which superseded Indigenous Australian customary law during colonisation. Australia is a common-law jurisdiction, its court system having originated in the common law system of English law. The country's common law is the same across the states and territories.

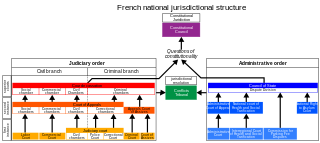

French law has a dual jurisdictional system comprising private law, also known as judicial law, and public law.

South Africa has a 'hybrid' or 'mixed' legal system, formed by the interweaving of a number of distinct legal traditions: a civil law system inherited from the Dutch, a common law system inherited from the British, and a customary law system inherited from indigenous Africans. These traditions have had a complex interrelationship, with the English influence most apparent in procedural aspects of the legal system and methods of adjudication, and the Roman-Dutch influence most visible in its substantive private law. As a general rule, South Africa follows English law in both criminal and civil procedure, company law, constitutional law and the law of evidence; while Roman-Dutch common law is followed in the South African contract law, law of delict (tort), law of persons, law of things, family law, etc. With the commencement in 1994 of the interim Constitution, and in 1997 its replacement, the final Constitution, another strand has been added to this weave.

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, and highcourt of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of a supreme court are binding on all other courts in a nation and are not subject to further review by any other court. Supreme courts typically function primarily as appellate courts, hearing appeals from decisions of lower trial courts, or from intermediate-level appellate courts. A supreme court can also, in certain circumstances, act as a court of original jurisdiction.

Roman-Dutch law is an uncodified, scholarship-driven, and judge-made legal system based on Roman law as applied in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. As such, it is a variety of the European continental civil law or ius commune. While Roman-Dutch law was superseded by Napoleonic codal law in the Netherlands proper as early as the beginning of the 19th century, the legal practices and principles of the Roman-Dutch system are still applied actively and passively by the courts in countries that were part of the Dutch colonial empire, or countries which are influenced by former Dutch colonies: Guyana, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Suriname, and the formerly Indonesian-occupied East Timor. It also heavily influenced Scots law. It also had some minor impact on the laws of the American state of New York, especially in introducing the office of Prosecutor (schout-fiscaal).

Widow inheritance is a cultural and social practice whereby a widow is required to marry a male relative of her late husband, often his brother. The practice is more commonly referred as a levirate marriage, examples of which can be found in ancient and biblical times.

Africa's fifty-six sovereign states range widely in their history and structure, and their laws are variously defined by customary law, religious law, common law, Western civil law, other legal traditions, and combinations thereof.

Ismail Mahomed SCOB SC was a South African Memon lawyer and jurist who served as the first post-Apartheid Chief Justice of South Africa from January 1997 until his death in June 2000. He was also the Chief Justice of Namibia from 1992 to 1999 and the inaugural Deputy President of the Constitutional Court of South Africa from 1995 to 1996.

The courts of South Africa are the civil and criminal courts responsible for the administration of justice in South Africa. They apply the law of South Africa and are established under the Constitution of South Africa or under Acts of the Parliament of South Africa.

Law in the Republic of Vanuatu consists of a mixed system combining the legacy of English common law, French civil law and indigenous customary law. The Parliament of Vanuatu is the primary law-making body today, but pre-independence French and British statutes, English common law principles and indigenous custom all enjoy constitutional and judicial recognition to some extent.

South African customary law refers to a usually uncodified legal system developed and practised by the indigenous communities of South Africa. Customary law has been defined as

an established system of immemorial rules evolved from the way of life and natural wants of the people, the general context of which was a matter of common knowledge, coupled with precedents applying to special cases, which were retained in the memories of the chief and his councilors, their sons and their sons' sons until forgotten, or until they became part of the immemorial rules.

South African jurisprudence refers to the study and theory of South African law. Jurisprudence has been defined as "the study of general theoretical questions about the nature of laws and legal systems."

The judiciary of Namibia consists of a three-tiered set of courts, the Lower, High and Supreme Courts. Parallel to this structure there are traditional courts dealing with minor matters and applying customary law.

In civil law jurisdictions, marital power was a doctrine in terms of which a wife was legally an incapax under the usufructory tutorship of her husband. The marital power included the power of the husband to administer both his wife's separate property and their community property. A wife was not able to leave a will, enter into a contract, or sue or be sued, in her own name or without the permission of her husband. It is very similar to the doctrine of coverture in the English common law, as well as to the Head and Master law property laws.

In Carelse v Estate De Vries, an important case in South African succession law, Carelse was seduced, on the promise of marriage, by the deceased. Carelse and the deceased continued their relationship, which produced seven children, before the deceased died intestate.

The Southern Africa Litigation Centre or SALC is a non-profit organisation based in Johannesburg, South Africa. It was founded in 2005 by Dr. Mark Ellis and Dr. Tawanda Mutasah. They conceptualised the organisation and hired Nicole Fritz who served as the first director for ten years. Later, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh was appointed director and replaced by Anneke Meerkotter, who currently leads the organisation.

References

- Zimmermann, Reinhard and Visser, Daniel P. (1996) Southern Cross: Civil Law and Common Law in South Africa Clarendon Press, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-826087-3 ;

- Joubert, W. A. et al. (2004) The Law of South Africa LexisNexis Butterworths, Durban, South Africa, ISBN 0-409-00448-0 ;