A clown is a person who performs comedy and arts in a state of open-mindedness using physical comedy, typically while wearing distinct makeup or costuming and reversing folkway-norms. Clowns have a varied tradition with significant variations in costume and performance. The most recognisable clowns are those that commonly perform in the circus, characterized by colorful wigs, red noses, and oversized shoes. However, clowns have also played roles in theater and folklore, like the court jesters of the Middle Ages and the jesters and ritual clowns of various indigenous cultures. Their performances can elicit a range of emotions, from humor and laughter to fear and discomfort, reflecting complex societal and psychological dimensions. Through the centuries, clowns have continued to play significant roles in society, evolving alongside changing cultural norms and artistic expressions.

Harlequin is the best-known of the comic servant characters (Zanni) from the Italian commedia dell'arte, associated with the city of Bergamo. The role is traditionally believed to have been introduced by the Italian actor-manager Zan Ganassa in the late 16th century, was definitively popularized by the Italian actor Tristano Martinelli in Paris in 1584–1585, and became a stock character after Martinelli's death in 1630.

Zanni, Zanni or Zane is a character type of commedia dell'arte best known as an astute servant and a trickster. The Zanni comes from the countryside and is known to be a "dispossessed immigrant worker". Through time, the Zanni grew to be a popular figure who was first seen in commedia as early as the 14th century. The English word "zany" derives from this character. The longer the nose on the characters mask, the more foolish the character.

Brighella is a comic, masked character from the Italian theatre style commedia dell'arte. His early costume consisted of loosely fitting, white smock and pants with green trim and was often equipped with a batocio or slap stick, or else with a wooden sword. Later he took to wearing a sort of livery with a matching cape. He wore a greenish half-mask displaying a look of preternatural lust and greed. It is distinguished by a hook nose and thick lips, along with a thick twirled mustache to give him an offensive characteristic. He evolved out of the general Zanni, as evidenced by his costume, and came into his own around the start of the 16th century.

Columbina is a stock character in the commedia dell'arte. She is Harlequin's mistress, a comic servant playing the tricky slave type, and wife of Pierrot. Rudlin and Crick use the Italian spelling Colombina in Commedia dell'Arte: A Handbook for Troupes.

Innamorati were stock characters within the theatre style known as commedia dell'arte, who appeared in 16th-century Italy. In the plays, everything revolved around the lovers in some regard. These dramatic and posh characters were present within commedia plays for the sole purpose of being in love with one another, and moreover, with themselves. These characters move elegantly and smoothly, and their young faces are unmasked unlike other commedia dell'arte characters. Despite facing many obstacles, the lovers were always united by the end.

Harlequinade is an English comic theatrical genre, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "that part of a pantomime in which the harlequin and clown play the principal parts". It developed in England between the 17th and mid-19th centuries. It was originally a slapstick adaptation or variant of the commedia dell'arte, which originated in Italy and reached its apogee there in the 16th and 17th centuries. The story of the Harlequinade revolves around a comic incident in the lives of its five main characters: Harlequin, who loves Columbine; Columbine's greedy and foolish father Pantaloon, who tries to separate the lovers in league with the mischievous Clown; and the servant, Pierrot, usually involving chaotic chase scenes with a bumbling policeman.

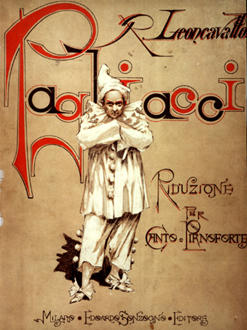

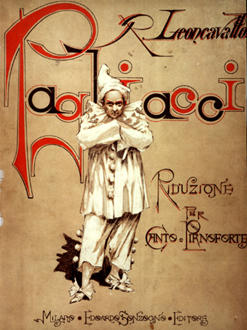

Pagliacci is an Italian opera in a prologue and two acts, with music and libretto by Ruggero Leoncavallo. The opera tells the tale of Canio, actor and leader of a commedia dell'arte theatrical company, who murders his wife Nedda and her lover Silvio on stage during a performance. Pagliacci premiered at the Teatro Dal Verme in Milan on 21 May 1892, conducted by Arturo Toscanini, with Adelina Stehle as Nedda, Fiorello Giraud as Canio, Victor Maurel as Tonio, and Mario Ancona as Silvio. Soon after its Italian premiere, the opera played in London and in New York. Pagliacci is the composer's only opera that is still widely performed.

Zan Ganassa was the stage name of an early actor-manager of commedia dell'arte, whose company was one of the first to tour outside Italy. Ganassa's real name was probably Alberto Naseli.

The Servant of Two Masters is a comedy by the Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni written in 1746. Goldoni originally wrote the play at the request of actor Antonio Sacco, one of the great Harlequins in history. His earliest drafts had large sections that were reserved for improvisation, but he revised it in 1789 in the version that exists today. The play draws on the tradition of the earlier Italian commedia dell'arte.

Pedrolino is a primo ("first") Zanni, or comic servant, of the commedia dell'arte; the name is a hypocorism of Pedro (Peter), via the suffix -lino. The character made its first appearance in the last quarter of the 16th century, apparently as the invention of the actor with whom the role was to be long identified, Giovanni Pellesini. Contemporary illustrations suggest that his white blouse and trousers constituted "a variant of the typical Zanni suit", and his Bergamasque dialect marked him as a member of the "low" rustic class. But if his costume and social station were without distinction, his dramatic role was certainly not: as a multifaceted first Zanni, his character was—and still is—rich in comic incongruities.

I Gelosi was an Italian acting troupe that performed commedia dell'arte from 1569 to 1604. Their name stems form their motto: Virtù, fama ed honor ne fèr gelosi, long thought to mean "Virtue, fame and honour made us jealous", or "We are jealous of attaining virtue, fame, and honour", signifying that such rewards could only be attained by those who sought for them jealously. Modern reevaluations have considered "zealous" as a more accurate translation over "jealous", redefining their motto to signify that, as actors, they were zealous to please.

Le Médecin volant is a French play by Molière, The date of its actual premiere is unknown, but its Paris premiere took place on 18 April 1659. Parts of the play were later reproduced in L'Amour médecin, and Le Médecin malgré lui. It is composed of 15 scenes and has seven characters largely based on stock commedia dell'arte roles.

Tristano Martinelli, called Dominus Arlecchinorum, the "Master of Harlequins", was an Italian actor in the commedia dell'arte tradition. He is probably the first actor to use the name "Harlequin" for the secondo ("second") Zanni role.

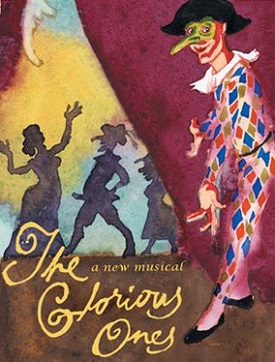

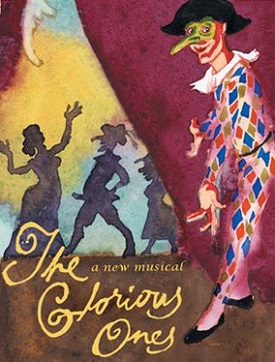

The Glorious Ones is a musical with book and lyrics by Lynn Ahrens and music by Stephen Flaherty. Set in 17th-century Italy, it concerns a theatre group in the world of commedia dell'arte and theatre of the Italian Renaissance.

Commedia dell'arte was an early form of professional theatre, originating from Italian theatre, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. It was formerly called Italian comedy in English and is also known as commedia alla maschera, commedia improvviso, and commedia dell'arte all'improvviso. Characterized by masked "types", commedia was responsible for the rise of actresses such as Isabella Andreini and improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios. A commedia, such as The Tooth Puller, is both scripted and improvised. Characters' entrances and exits are scripted. A special characteristic of commedia is the lazzo, a joke or "something foolish or witty", usually well known to the performers and to some extent a scripted routine. Another characteristic of commedia is pantomime, which is mostly used by the character Arlecchino, now better known as Harlequin.

Flaminio Scala, commonly known by his stage name, Flavio, was an Italian stage actor of Commedia dell'Arte, scenario writer, playwright, director, producer, manager, agent, and editor. Considered one of the most important figures in Renaissance theatre, Scala is remembered today as the author of the first published collection of commedia scenarios, Il Teatro delle Favole Rappresentative, short comic plays that served as inspiration to playwrights such as Lope de Vega, William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Molière.

i Sebastiani is a Commedia dell'Arte theatre troupe formed in 1990 by Jeff Hatalsky. To the present day, i Sebastiani has performed for thousands of fans across the United States and Canada. The company has travelled as far as Montreal to the north, Miami to the south, and Texas to the west, performing more than 100 different improvisational scenarios.

Each character in Commedia dell'arte is distinctly different, and defined by their movement, actions, masks, and costumes. These costumes show their social status and background.

Commedia dell'arte masks are a type of mask worn by performers of the Italian form of theatre, Commedia dell'arte. Masks are an integral part of the performance, and each character wears a particular mask design. All masks were originally leather but are now more commonly made of neoprene. They are an extension of the actors and their costumes, hair, and accessories. The masks create an entirely different face for the people wearing them. Masks in Commedia dell'arte speak of the types of characters that each represents, saying that they are an unchanged type.