An electric light, lamp, or light bulb is an electrical component that produces light. It is the most common form of artificial lighting. Lamps usually have a base made of ceramic, metal, glass, or plastic which secures the lamp in the socket of a light fixture, which is often called a "lamp" as well. The electrical connection to the socket may be made with a screw-thread base, two metal pins, two metal caps or a bayonet mount.

Thomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, which include the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and early versions of the electric light bulb, have had a widespread impact on the modern industrialized world. He was one of the first inventors to apply the principles of organized science and teamwork to the process of invention, working with many researchers and employees. He established the first industrial research laboratory.

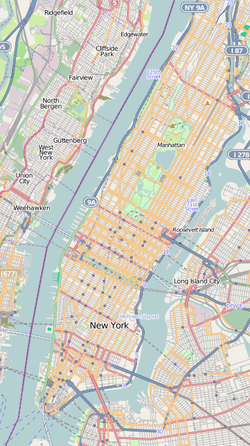

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and neighborhood in the Midtown Manhattan section of New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street. Together with adjacent Duffy Square, Times Square is a bowtie-shaped plaza five blocks long between 42nd and 47th Streets.

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a filament that is heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb that is either evacuated or filled with inert gas to protect the filament from oxidation. Electric current is supplied to the filament by terminals or wires embedded in the glass. A bulb socket provides mechanical support and electrical connections.

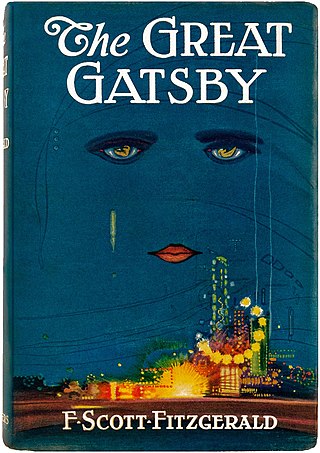

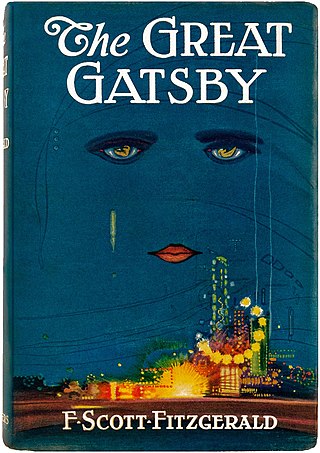

The Great Gatsby is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with Jay Gatsby, the mysterious millionaire with an obsession to reunite with his former lover, Daisy Buchanan.

The National Electric Light Association (NELA) was a national United States trade association that included the operators of electric central power generation stations, electrical supply companies, electrical engineers, scientists, educational institutions and interested individuals. Founded in 1885 by George S. Bowen, Franklin S. Terry and Charles A. Brown, it represented the interests of private companies involved in the fledgling electric power industry that included companies like General Electric, Westinghouse and most of the country's electric companies. The NELA played a dominant role in promoting the interests and expansion of the U.S. commercial electric industry. The association's conventions became a major clearinghouse for technical papers covering the entire field of electricity and its development, with a special focus on the components needed for centralized power stations or power plants. In 1895 the association sponsored a conference that led to the issue of the first edition of the U.S. National Electrical Code. Its rapid growth mirrored the development of electricity in the U.S. that included regional and statewide affiliations across the country and Canada. It was the forerunner of the Edison Electric Institute. Its highly aggressive battle against municipal ownership of electric production led to extensive federal hearings between 1928 and 1935 that led to its demise. Its logo is an early depiction of Ohm's law which is "C equals E divided by R," or "the current strength in any circuit is equal to the electromotive force divided by the resistance," or the basic law of electricity. It was established in 1827 by Dr. G. S. Ohm.

This Side of Paradise is a 1920 debut novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. It examines the lives and morality of carefree American youth at the dawn of the Jazz Age. Its protagonist, Amory Blaine, is a handsome middle-class student at Princeton University who dabbles in literature and engages in a series of unfulfilling romances with young women. The novel explores themes of love warped by greed and social ambition. Fitzgerald, who took inspiration for the title from a line in Rupert Brooke's poem Tiare Tahiti, spent years revising the novel before Charles Scribner's Sons accepted it for publication.

Daniel McFarlan Moore was an American electrical engineer and inventor. He developed a novel light source, the "Moore lamp", and a business that produced them in the early 1900s. The Moore lamp was the first commercially viable light-source based on gas discharges instead of incandescence; it was the predecessor to contemporary neon lighting and fluorescent lighting. In his later career Moore developed a miniature neon lamp that was extensively used in electronic displays, as well as vacuum tubes that were used in early television systems.

Ben Hur is a 1907 American silent drama film set in ancient Rome, the first screen adaptation of Lew Wallace's popular 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. Co-directed by Sidney Olcott and Frank Oakes Rose, this "photoplay" was produced by the Kalem Company of New York City, and its scenes, including the climactic chariot race, were filmed in the city's borough of Brooklyn.

Neon lighting consists of brightly glowing, electrified glass tubes or bulbs that contain rarefied neon or other gases. Neon lights are a type of cold cathode gas-discharge light. A neon tube is a sealed glass tube with a metal electrode at each end, filled with one of a number of gases at low pressure. A high potential of several thousand volts applied to the electrodes ionizes the gas in the tube, causing it to emit colored light. The color of the light depends on the gas in the tube. Neon lights were named for neon, a noble gas which gives off a popular orange light, but other gases and chemicals called phosphors are used to produce other colors, such as hydrogen (purple-red), helium, carbon dioxide (white), and mercury (blue). Neon tubes can be fabricated in curving artistic shapes, to form letters or pictures. They are mainly used to make dramatic, multicolored glowing signage for advertising, called neon signs, which were popular from the 1920s to 1960s and again in the 1980s.

The Marble Hill–225th Street station is a local station on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line of the New York City Subway. Located at the intersection of Broadway and 225th Street in the Marble Hill neighborhood of Manhattan, it is served by the 1 train at all times.

Jay Gatsby is the titular fictional character of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby. The character is an enigmatic nouveau riche millionaire who lives in a luxurious mansion on Long Island where he often hosts extravagant parties and who allegedly gained his fortune by illicit bootlegging during prohibition in the United States. Fitzgerald based many details about the fictional character on Max Gerlach, a mysterious neighbor and World War I veteran whom the author met in New York during the raucous Jazz Age. Like Gatsby, Gerlach threw lavish parties, never wore the same shirt twice, used the phrase "old sport", claimed to be educated at Oxford University, and fostered myths about himself, including that he was a relation of the German Kaiser.

The Knickerbocker Theatre, previously known as Abbey's Theatre and Henry Abbey's Theatre, was a Broadway theatre located at 1396 Broadway in New York City. It operated from 1893 to 1930. In 1906, the theatre introduced the first moving electrical sign on Broadway to advertise its productions.

Schuyler Skaats Wheeler was an American electrical engineer and manufacturer who invented the electric fan, an electric elevator design, and the electric fire engine. He is associated with the early development of the electric motor industry, especially to do with training the blind in this industry for gainful employment. He helped develop and implement a code of ethics for electrical engineers and was associated with the electrical field in one way or another for over thirty years.

Nick Carraway is a fictional character and narrator in F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby. The character is a Yale University alumnus from the American Midwest, a World War I veteran, and a newly arrived resident of West Egg on Long Island, near New York City. He is a bond salesman and the neighbor of enigmatic millionaire Jay Gatsby. He facilitates a sexual affair between Gatsby and Nick's second cousin, once removed, Daisy Buchanan which becomes one of the novel's central conflicts. Carraway is easy-going and optimistic, although this latter quality fades as the novel progresses. After witnessing the callous indifference and insouciant hedonism of the idle rich during the riotous Jazz Age, he ultimately chooses to leave the eastern United States forever and returns to the Midwest.

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald, widely known simply as Scott Fitzgerald, was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age, a term he popularized in his short story collection Tales of the Jazz Age. During his lifetime, he published four novels, four story collections, and 164 short stories. Although he achieved temporary popular success and fortune in the 1920s, Fitzgerald received critical acclaim only after his death and is now widely regarded as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century.

William Joseph Hammer was an American pioneer electrical engineer, aviator, and president of the Edison Pioneers.

Thamara de Swirsky, sometimes seen as Tamara de Svirsky, Thamara Swirskaya, or Countess de Swirsky, was a Russian-born dancer, known for dancing barefoot.

Benjamin Moses Teal was an American actor, theater director, and playwright. He directed over 30 plays on Broadway between 1897 and 1916, and was widely known for his strict, often brusque stage direction. Born in Eugene, Oregon, Teal spent his formative years in San Francisco, where he began performing as a child actor in theatrical productions.

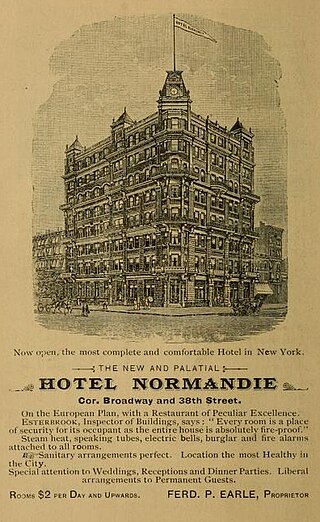

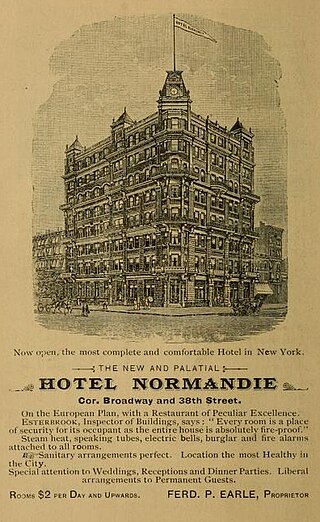

The Hotel Normandie was a luxury hotel located on Broadway at 38th Street in New York City. The 8-story building was put up by Ferdinand Earl, an heir of the Fisher family, opening in 1884. Amenities were advertised to include "Steam heat, speaking tubes, electric bells, burglar and fire alarms attached to all rooms". Rooms rates started at $2/day. Dinner was available for $1.25 additional; a quart bottle of Moët & Chandon champagne was $4.