Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U.S., and is said to have "helped lay the groundwork for the [American] Civil War".

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), which depicts the harsh conditions experienced by enslaved African Americans. The book reached an audience of millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and in Great Britain, energizing anti-slavery forces in the American North, while provoking widespread anger in the South. Stowe wrote 30 books, including novels, three travel memoirs, and collections of articles and letters. She was influential both for her writings as well as for her public stances and debates on social issues of the day.

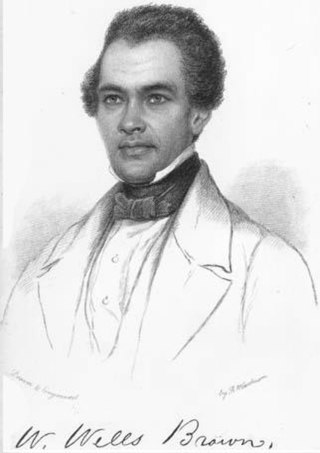

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society, who often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown, also a freedman, also often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had 1,350 local chapters with around 250,000 members.

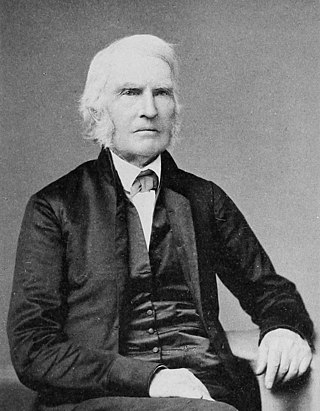

The New England Anti-Slavery Society (1831–1837) was formed by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator, in 1831. The Liberator was its official publication.

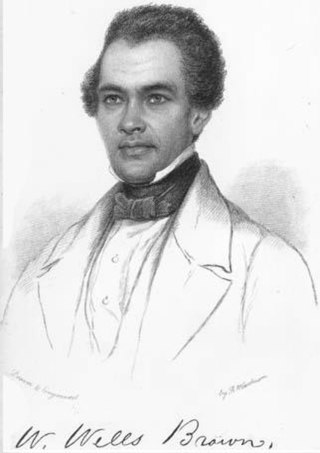

William Wells Brown was an American abolitionist, novelist, playwright, and historian. Born into slavery near Mount Sterling, Kentucky, Brown escaped to Ohio in 1834 at the age of 19. He settled in Boston, Massachusetts, where he worked for abolitionist causes and became a prolific writer. While working for abolition, Brown also supported causes including: temperance, women's suffrage, pacifism, prison reform, and an anti-tobacco movement. His novel Clotel (1853), considered the first novel written by an African American, was published in London, England, where he resided at the time; it was later published in the United States.

Samuel Ringgold Ward was an African American who escaped enslavement to become an abolitionist, newspaper editor, labor leader, and Congregational church minister.

David Ruggles was an African-American abolitionist in New York who resisted slavery by his participation in a Committee of Vigilance and the Underground Railroad to help fugitive slaves reach free states. He was a printer in New York City during the 1830s, who also wrote numerous articles, and "was the prototype for black activist journalists of his time." He claimed to have led more than 600 fugitive slaves to freedom in the North, including Frederick Douglass, who became a friend and fellow activist. Ruggles opened the first African-American bookstore in 1834.

James Mott was a Quaker leader, teacher, merchant, and anti-slavery activist. He was married to suffragist leader Lucretia Mott. Like her, he wanted enslaved people to be freed. He helped found anti-slavery organizations, participated in the "free-produce movement", and operated an Underground Railroad depot with their family. The Motts concealed Henry "Box" Brown after he had been shipped from Richmond, Virginia in a crate. Mott also supported women's rights, chairing the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. He spent four years supporting the establishment of Swarthmore College.

William Cooper Nell was an American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Writing for abolitionist newspapers The Liberator and The North Star, he helped publicize the anti-slavery cause. He published the North Star from 1847 to 18xx, moving temporarily to Rochester, New York.

George William Alexander (1802–1890) was an English financier and philanthropist. He was the founding treasurer of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1839. The American statesman Frederick Douglass said that he "has spent more than an American fortune in promoting the anti-slavery cause ..."

Mary Grew was an American abolitionist and suffragist whose career spanned nearly the entire 19th century. She was a leader of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. She was one of eight women delegates who were denied their seats at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840. An editor and journalist, she wrote for abolitionist newspapers and chronicled the work of Philadelphia's abolitionists over more than three decades. She was a gifted public orator at a time when it was still noteworthy for women to speak in public. Her obituary summarized her impact: "Her biography would be a history of all reforms in Pennsylvania for fifty years."

Stephen Symonds Foster was a radical American abolitionist known for his dramatic and aggressive style of public speaking, and for his stance against those in the church who failed to fight slavery. His marriage to Abby Kelley brought his energetic activism to bear on women's rights. He spoke out for temperance, and agitated against any government, including his own, that would condone slavery.

American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses is a book written by the American abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld, his wife Angelina Grimké, and her sister Sarah Grimké, which was published in 1839.

Sarah Mapps Douglass was an American educator, abolitionist, writer, and public lecturer. Her painted images on her written letters may be the first or earliest surviving examples of signed paintings by an African-American woman. These paintings are contained within the Cassey Dickerson Album, a rare collection of 19th-century friendship letters between a group of women.

William Gustavus Allen was an African-American academic, intellectual, and lecturer. For a time he co-edited The National Watchman, an abolitionist newspaper. While studying law in Boston he lectured widely on abolition, equality, and integration. He was then appointed a professor of rhetoric and Greek at New-York Central College, the second African-American college professor in the United States. He saw himself as an academic and intellectual.

James Cropper (1773–1840) was an English businessman and philanthropist, known as an abolitionist who made a major contribution to the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833.

Amy Matilda Williams Cassey was an African American abolitionist, and was active with the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Cassey was a member of the group of elite African Americans who founded the Gilbert Lyceum, Philadelphia's first co-ed literary society. The society had more than forty registered members by the end of the first year.

Wilson Armistead was a Quaker, businessman, abolitionist and writer from Leeds. He led the Leeds Anti-Slavery Association and wrote and edited anti-slavery texts. His best known work, A Tribute for the Negro, was published in 1848 in which he describes slavery as "the most extensive and extraordinary system of crime the world ever witnessed". In 1851 he hosted Ellen and William Craft, including them on the census return as 'fugitive slaves' in an act that has been described as "guerrilla inscription".

Abolitionist children’s literature includes works written for children by authors committed to the movement to end slavery. It aimed to instill in young readers an understanding of slavery, racial hierarchies, sympathy for the enslaved, and a desire for emancipation. A variety of literary forms were used by abolitionist children’s authors including, short stories, poems, songs, nursery rhymes and dialogues, much of it written by white women. Pamphlets, picture books and periodicals were the primary forms of abolitionist children’s literature, often using Biblical themes to reinforce the wickedness of slavery. Abolitionist children's literature was countered with pro-slavery material aimed at children, which attempting to depict slavery as a noble pursuit, and slaves as stupid and grateful, or evil.

A Tribute for the Negro: Being a Vindication of the Moral, Intellectual, and Religious Capabilities of the Coloured Portion of Mankind; with Particular Reference to the African Race is an 1848 work written by the Leeds-based British abolitionist Wilson Armistead, that published indictments of scientific racism, as well as slavery, and included biographies of a number of prominent campaigners including Henry Highland Garnet and Phyllis Wheatley. It was one of a number of anti-slavery books published in the 1800s by social reformers. The book was dedicated to James Pennington, Frederick Douglass, Alexander Crummell, "as well as many other elevated noble examples of elevated humanity of the negro". Its purpose was to argue and present evidence for the accomplishments of African Americans and act as a treatise of support. One of the didactic tools used by Armistead in the book is to draw comparisons between Britain's Roman past and its cruelties, to argue for more progressive views on abolition. The book was published by subscription with an extensive list of nearly 1000 subscribers comprising the most 'conspicuous' philanthropists of the day and including "the Sovereign of the most enlightened country of the world", which it has been suggested refers to Queen Victoria.