Related Research Articles

Russian is an East Slavic language, spoken primarily in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living East Slavic languages, and is also a part of the larger Balto-Slavic languages. It was the de facto and de jure official language of the former Soviet Union. Russian has remained an official language in independent Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, and is still commonly used as a lingua franca in Ukraine, Moldova, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and to a lesser extent in the Baltic states and Israel.

Russification, or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian culture and the Russian language.

Korenizatsiia was an early policy of the Soviet Union for the integration of non-Russian nationalities into the governments of their specific Soviet republics. In the 1920s, the policy promoted representatives of the titular nation, and their national minorities, into the lower administrative levels of the local government, bureaucracy, and nomenklatura of their Soviet republics. The main idea of the korenizatsiia was to grow communist cadres for every nationality. In Russian, the term korenizatsiya (коренизация) derives from korennoye naseleniye. The policy practically ended in the mid-1930s with the deportations of various nationalities.

Russians in the Baltic states is a broadly defined subgroup of the Russian diaspora who self-identify as ethnic Russians, or are citizens of Russia, and live in one of the three independent countries — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — primarily the consequences of the USSR's forced population transfers during occupation. As of 2023, there were approximately 887,000 ethnic Russians in the three countries, having declined from ca 1.7 million in 1989, the year of the last census during the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation of the three Baltic countries.

Ukrainization is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of Ukrainian culture in various spheres of public life such as education, publishing, government, and religion. The term is also used to describe a process by which non-Ukrainians or Russian-speaking Ukrainians are assimilated to Ukrainian culture and language.

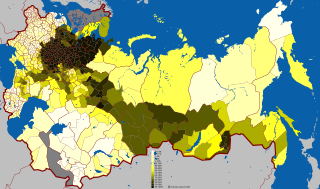

This article details the geographical distribution of Russian-speakers. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the status of the Russian language often became a matter of controversy. Some Post-Soviet states adopted policies of derussification aimed at reversing former trends of Russification, while Belarus under Alexander Lukashenko and the Russian Federation under Vladimir Putin reintroduced Russification policies in the 1990s and 2000s, respectively.

Starting in September 2018, 12-year secondary education will replace 11-year which was mandatory before that. As a rule, schooling begins at the age of 6, unless your birthday is on or after 1 September. In 2016/17, the number of students in primary and secondary school reached 3,846,000, in vocational school 285,800, and in higher education 1,586,700 students. According to 2017 EduConf speech of the (then) Minister of Education and Science of Ukraine, Liliya Hrynevych, the amount of budget financing for the sphere of education would reach about ₴53 billion in 2017.

The languages of the Soviet Union consist of hundreds of different languages and dialects from several different language groups.

Russian is the most common first language in the Donbas and Crimea regions of Ukraine and the city of Kharkiv, and the predominant language in large cities in the eastern and southern portions of the country. The usage and status of the language is the subject of political disputes. Ukrainian is the country's only state language since the adoption of the 1996 Constitution, which prohibits an official bilingual system at state level but also guarantees the free development, use and protection of Russian and other languages of national minorities. In 2017 a new Law on Education was passed which restricted the use of Russian as a language of instruction. Nevertheless, Russian remains a widely used language in Ukraine in pop culture and in informal and business communication.

Non-citizens or aliens in Latvian law are individuals who are not citizens of Latvia or any other country, but who, in accordance with the Latvian law "Regarding the status of citizens of the former USSR who possess neither Latvian nor other citizenship," have the right to a non-citizen passport issued by the Latvian government as well as other specific rights. Approximately two thirds of them are ethnic Russians, followed by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, and Lithuanians.

Articles 4 and 114 of the Constitution of Latvia form the foundation for language policy in Latvia, declaring Latvian to be the official state language and affirming the rights of ethnic minorities to preserve and develop their languages. Livonian language is recognized as "the language of the indigenous (autochthon) population" in the Official Language Law, but Latgalian written language is protected as "a historic variant of Latvian." All other languages are considered foreign by the Law on State Language. Latvia provides national minority education programmes in Russian, Polish, Hebrew, Ukrainian, Estonian, Lithuanian, and Belarusian.

Human rights in Latvia are generally respected by the government, according to the US Department of State and Freedom House. Latvia is ranked above-average among the world's sovereign states in democracy, press freedom, privacy and human development. The country has a relatively large ethnic Russian community, which has basic rights guaranteed under the constitution and international human rights laws ratified by the Latvian government.

Russian influence operationsin Estonia consist of the alleged actions taken by the government of the Russian Federation to produce a favorable political and social climate in the Republic of Estonia. According to the Estonian Internal Security Service, Russian influence operations in Estonia form a complex system of financial, political, economic and espionage activities in Republic of Estonia for the purposes of influencing Estonia's political and economic decisions in ways considered favourable to the Russian Federation and conducted under the doctrine of near abroad. Conversely, the ethnic Russians in Estonia generally take a more sympathetic view of Moscow than that of the Estonian government. According to some, such as Professor Mark A. Cichock of the University of Texas at Arlington, the Russian government has actively pursued the imposition of a dependent relationship upon the Baltic states, with the desire to remain the region's dominant actor and political arbiter, continuing the Soviet pattern of hegemonic relations with these small neighbouring states. According to the Centre for Geopolitical Studies, the Russian information campaign which the centre characterises as a "real mud throwing" exercise, has provoked a split in Estonian society amongst Russian speakers, inciting some to riot over the relocation of the Bronze Soldier. The 2007 cyberattacks on Estonia is considered to be an information operation against Estonia, with the intent to influence the decisions and actions of the Estonian government. While Russia denies any direct involvement in the attacks, hostile rhetoric from the political elite via the media influenced people to attack.

Human rights in Estonia are acknowledgedas being generally respected by the government. Nevertheless, there are concerns in some areas, such as detention conditions, excessive police use of force, and child abuse. Estonia has been classified as a flawed democracy, with moderate privacy and human development in Europe. Individuals are guaranteed on paper the basic rights under the constitution, legislative acts, and treaties relating to human rights ratified by the Estonian government. As of 2023, Estonia was ranked 8th in the world by press freedoms.

Latvian Human Rights Committee is a non-governmental human rights organization in Latvia. It is a member of international human rights and anti-racism NGOs FIDH, AEDH. Co-chairpersons of LHRC are Vladimir Buzayev and Natalia Yolkina. According to the authors of the study "Ethnopolitics in Latvia", former CBSS Commissioner on Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Ole Espersen "had visited LHRC various times and had used mostly the data of that organisation in his views on Latvia".

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Lake Peipus and Russia. The territory of Estonia consists of the mainland, the larger islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, and over 2,300 other islands and islets on the east coast of the Baltic Sea, covering a total area of 45,335 square kilometres (17,504 sq mi). Tallinn, the capital city, and Tartu are the two largest urban areas. The Estonian language is the indigenous and official language. It is the first language of the majority of the population of 1.4 million.

Language Inspectorate is a governmental body under the Ministry of Education of Estonia. The inspectorate was founded in 1990 as the State Language Board with the mandate to, as the Commissioner for Human Rights states, to facilitate the republic's expectation that people offering services to the public should speak Estonian. Since 1995, its director is Ilmar Tomusk. It carries out state supervision with the primary task to ensure that the Language Act and other legal acts regulating language use are observed. Non-observance of the Language Act may result in warnings, written orders or fines.

Language policy in Ukraine is based on its Constitution, international treaties and on domestic legislation. According to article 10 of the Constitution, Ukrainian is the official language of Ukraine, and the state shall ensure the comprehensive development and functioning of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of social life throughout the entire territory of the country. Some minority languages have significantly less protection, and have restrictions on their public usage.

The Russian language in Latvia is spoken by a significant minority. According to the External Migration Survey in 2017, it was the native language of 36% of the population, whereas 25.4% of the population were ethnic Russians.

Derussification is a process or public policy in different states of the former Russian Empire and the Soviet Union or certain parts of them, aimed at restoring national identity of indigenous peoples: their language, culture and historical memory, lost due to Russification. The term may also refer to the marginalization of the Russian language, culture and other attributes of the Russian-speaking society through the promotion of other, usually autochthonous, languages and cultures.

References

- ↑ Birckenbach, Hanne-Margret (2000). Half full or half empty?: the OSCE mission to Estonia and its balance sheet 1993–1999 (PDF). European Centre for Minority Issues. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ Organisations participating in the Fundamental Rights Platform Archived 22 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Partners lichr.ee

- ↑ "AEDH: Member Leagues". Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ↑ Member organisations in Estonia Archived 7 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ List of supporters Archived 10 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Центр информации по правам человека - о нас". Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ↑ "Annual Review" (PDF). www.kapo.ee. Estonia. 2008. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ↑ Amnesty International Report 2010 p. 139

- 1 2 Legal Information Centre for Human Rights; Russkiy Mir Foundation (2010). Russian Schools of Estonia. Compendium of Materials (PDF). Legal Information Centre for Human Rights. ISBN 978-9985-9967-2-0.

- ↑ Vetik, Raivo; Jelena Helemäe (2011). The Russian Second Generation in Tallinn and Kohtla-Järve: The TIES Study in Estonia. Amsterdam University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-90-8964-250-9.

- ↑ Pavlenko, Aneta (2008). Multilingualism in post-Soviet countries. Multilingual Matters. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-84769-087-6.

- ↑ Current politics and economics of Russia, Volume 3. Nova Science Publishers. 1992. p. 78.

- ↑ Pourchot, Georgeta (2008). Eurasia rising: democracy and independence in the post-Soviet space. ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-275-99916-2.

- ↑ Brown, Kara (2011). "The State, Official-Language Education, and Minorities: Estonian-Language Instruction for Estonia's Russian-Speakers". In Bekerman, Zvi (ed.). International Handbook of Migration, Minorities and Education: Understanding Cultural and Social Differences in Processes of Learning. Thomas Geisen. Springer. p. 202. ISBN 978-94-007-1465-6.

De jure Russification during the Soviet occupation of Estonia (1940–1991) was driven by three models: (1) Russian monolingualism for Russians with minimal, if any Estonian-language instruction; (2) Estonian-Russian bilingualism for ethnic Estonians; and (3) assimilation of other non-Russian and non-Estonian ethnicities. In practice, Russification meant an increase in Russian-language instruction in Estonian-medium schools, the rapid expansion of the Russian-medium school network, and the marginalization of Estonian-language education in Russian-medium schools.

- ↑ Ott Tammik (22 December 2011). "Minister: Russian Schools Are Here to Stay". ERR. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Аавиксоо: русские школы в Эстонии никуда не исчезнут ERR (in Russian)

- ↑ Recommendations of the Forum on Minority Issues A/HRC/10/11/Add.1 — para. 27

- ↑ Yves Daudet, Pierre Michel Eisemann Commentary on the Convention against Discrimination in Education UNESCO, 2005