Currently, the politics of Sudan takes place in the framework of a federal provisional government. Previously, a president was head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces in a de jure multi-party system. Legislative power was officially vested in both the government and in the two chambers, the National Assembly (lower) and the Council of States (higher), of the bicameral National Legislature. The judiciary is independent and obtained by the Constitutional Court. However, following a deadly civil war and the still ongoing genocide in Darfur, Sudan was widely recognized as a totalitarian state where all effective political power was held by President Omar al-Bashir and his National Congress Party (NCP). However, al-Bashir and the NCP were ousted in a military coup which occurred on April 11, 2019. The government of Sudan was then led by the Transitional Military Council or TMC. On 20 August 2019, the TMC dissolved giving its authority over to the Sovereignty Council of Sudan, who were planned to govern for 39 months until 2022, in the process of transitioning to democracy. However, the Sovereignty Council and the Sudanese government were dissolved in October 2021.

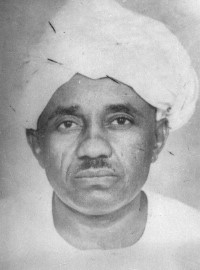

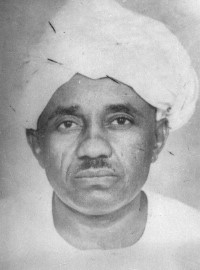

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry was a Sudanese military officer and politician who served as the fourth head of state of Sudan from 1969 to 1985, first as Chairman of the National Revolutionary Command Council and then as President.

Hassan al-Turabi was a Sudanese politician and scholar. He was the alleged architect of the 1989 Sudanese military coup that overthrew Sadiq al-Mahdi and installed Omar al-Bashir as president. He has been called "one of the most influential figures in modern Sudanese politics" and a "longtime hard-line ideological leader". He was instrumental in institutionalizing Sharia in the northern part of the country and was frequently imprisoned in Sudan, but these "periods of detention" were "interspersed with periods of high political office".

The Second Sudanese Civil War was a conflict from 1983 to 2005 between the central Sudanese government and the Sudan People's Liberation Army. It was largely a continuation of the First Sudanese Civil War of 1955 to 1972. Although it originated in southern Sudan, the civil war spread to the Nuba mountains and the Blue Nile. It lasted for almost 22 years and is one of the longest civil wars on record. The war resulted in the independence of South Sudan 6 years after the war ended.

Sadiq al-Mahdi, also known as Sadiq as-Siddiq, was a Sudanese political and religious figure who was Prime Minister of Sudan from 1966 to 1967 and again from 1986 to 1989. He was head of the National Umma Party and Imam of the Ansar, a Sufi order that pledges allegiance to Muhammad Ahmad (1844–1885), who claimed to be the Mahdi, the messianic saviour of Islam.

The National Congress Party was a major political party that dominated domestic politics in Sudan from its foundation until the Sudanese Revolution.

The National Islamic Front was an Islamist political organization founded in 1976 and led by Dr. Hassan al-Turabi that influenced the Sudanese government starting in 1979, and dominated it from 1989 to the late 1990s. It was one of only two Islamic revival movements to secure political power in the 20th century.

This article details the period of Transitional Military Council, April 1985 to April 1986, in the history of Sudan. The combination of the south's redivision, the introduction throughout the country of the sharia, the renewed civil war, and growing economic problems eventually contributed to Gaafar Nimeiry's downfall. On April 6, 1985, a group of military officers, led by Lieutenant General Abdel Rahman Swar al-Dahab, overthrew Nimeiry, who took refuge in Egypt.

This article covers the period of the history of Sudan between 1985 and 2019 when the Sudanese Defense Minister Abdel Rahman Swar al-Dahab seized power from Sudanese President Gaafar Nimeiry in the 1985 Sudanese coup d'état. Not long after, Lieutenant General Omar al-Bashir, backed by an Islamist political party, the National Islamic Front, overthrew the short lived government in a coup in 1989 where he ruled as President until his fall in April 2019. During Bashir's rule, also referred to as Bashirist Sudan, or as they called themselves the al-Ingaz regime, he was re-elected three times while overseeing the independence of South Sudan in 2011. His regime was criticized for human rights abuses, atrocities and genocide in Darfur and allegations of harboring and supporting terrorist groups in the region while being subjected to United Nations sanctions beginning in 1995, resulting in Sudan's isolation as an international pariah.

The Government of Sudan is the federal provisional government created by the Constitution of Sudan having executive, parliamentary, and the judicial branches. Previously, a president was head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces in a de jure multi-party system. Legislative power was officially vested in both the government and in the two houses – the National Assembly (lower) and the Council of States (upper) – of the bicameral National Legislature. The judiciary is independent and obtained by the Constitutional Court. However, following the Second Sudanese Civil War and the still ongoing genocide in Darfur, Sudan was widely recognized as a totalitarian state where all effective political power was held by President Omar al-Bashir and his National Congress Party (NCP). However, al-Bashir and the NCP were ousted in a military coup on April 11, 2019. The government of Sudan was then led by the Transitional Military Council (TMC). On 20 August 2019, the TMC dissolved giving its authority over to the Transitional Sovereignty Council, who were planned to govern for 39 months until 2022, in the process of transitioning to democracy. However, the Sovereignty Council and the Sudanese government were dissolved in October 2021.

The Law of Egypt consists of courts, offences, and various types of laws. Egypt has its own constitution which took effect on 18 January 2014. The Constitution of Egypt is the fundamental law of the country. Egypts legal codes and court operations are based primarily on British, Italian, and Napoleonic models, and has been the inspiration for the civil code for numerous other Middle Eastern jurisdictions, including Jordan, Bahrain, Qatar, pre-dictatorship kingdoms of Libya and Iraq, and the commercial code of Kuwait.

Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, also known as Ustaz Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, was a Sudanese religious thinker, leader, and trained engineer. He developed what he called the "Second Message of Islam", which postulated that the verses of the Qur'an revealed in Medina were appropriate in their time as the basis of Islamic law, (Sharia), but that the verses revealed in Mecca represented the ideal and universal religion, which would be revived when humanity had reached a stage of development capable of implementing them, ushering in a renewed era of Islam based on the principles of freedom and equality. He was executed for apostasy for his religious preaching at the age of 76 by the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry.

The temporary de factoConstitution of Sudan is the Draft Constitutional Declaration, which was signed by representatives of the Transitional Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change alliance on 4 August 2019. This replaced the Interim National Constitution of the Republic of Sudan, 2005 (INC) adopted on 6 July 2005, which had been suspended on 11 April 2019 by Lt. Gen Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf in the 2019 Sudanese coup d'état.

The Supreme Court, located in Khartoum, is the highest judicial authority in Sudan, apart from the Constitutional Court, which under Article 30 of the August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration, is to be "an independent court, separate from the judicial authority." Nemat Abdullah Khair was appointed as Chief Justice of Sudan, thus becoming the President of the Supreme Court, on 10 October 2019.

The Law of Nigeria consists of courts, offences, and various types of laws. Nigeria has its own constitution which was established on 29 May 1999. The Constitution of Nigeria is the supreme law of the country. There are four distinct legal systems in Nigeria, which include English law, Common law, Customary law, and Sharia Law. English law in Nigeria is derived from the colonial Nigeria, while common law is a development from its post-colonial independence.

Sharia means Islamic law based on Islamic concepts based from Quran and Hadith. Since the early Islamic states of the eighth and ninth centuries, Sharia always existed alongside other normative systems.

Capital punishment in Sudan is legal under Article 27 of the Sudanese Criminal Act 1991. The Act is based on Sharia law which prescribes both the death penalty and corporal punishment, such as amputation. Sudan has moderate execution rates, ranking 8th overall in 2014 when compared to other countries that still continue the practice, after at least 29 executions were reported.

The judicial system of the United Arab Emirates is divided into federal courts and local courts. The federal justice system is defined in the Constitution of the United Arab Emirates, with the Federal Supreme Court based at Abu Dhabi. As of 2023, only the emirates of Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Ras Al Khaimah have local court systems, while all other emirates use the federal court system for all legal proceedings.

The Islamist movement in Sudan started in universities and high schools as early as the 1940s under the influence of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. The Islamic Liberation Movement, a precursor of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood, began in 1949. Hassan Al-Turabi then took control of it under the name of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood. In 1964, he became secretary-general of the Islamic Charter Front (ICF), an activist movement that served as the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood. Other Islamist groups in Sudan included the Front of the Islamic Pact and the Party of the Islamic Bloc.

In September 1983, Sudanese president Gaafar Nimeiry introduced Islamic sharia laws in Sudan, known as September Laws, disposing of alcohol and implementing hudud punishments such as public flogging for alcohol consumption and amputations for theft. Nimeiry declared himself the imam of the "Sudanese umma", leading to concerns about the undemocratic implementation of these laws. Hassan al-Turabi assisted with drafting the law and later supported the laws, unlike, the leader of the opposition, Sadiq al-Mahdi's dissenting view.