Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva was a Russian poet. Her work is considered among some of the greatest in twentieth century Russian literature. She lived through and wrote of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Moscow famine that followed it. In an attempt to save her daughter Irina from starvation, she placed her in a state orphanage in 1919, where she died of hunger. Tsvetaeva left Russia in 1922 and lived with her family in increasing poverty in Paris, Berlin and Prague before returning to Moscow in 1939. Her husband Sergei Efron and their daughter Ariadna (Alya) were arrested on espionage charges in 1941; her husband was executed. Tsvetaeva committed suicide in 1941. As a lyrical poet, her passion and daring linguistic experimentation mark her as a striking chronicler of her times and the depths of the human condition.

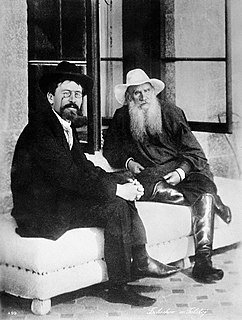

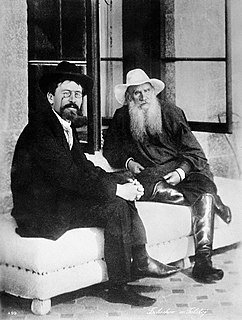

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia and its émigrés and to Russian-language literature. The roots of Russian literature can be traced to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in Old East Slavic were composed. By the Age of Enlightenment, literature had grown in importance, and from the early 1830s, Russian literature underwent an astounding golden age in poetry, prose and drama. Romanticism permitted a flowering of poetic talent: Vasily Zhukovsky and later his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore. Prose was flourishing as well. Mikhail Lermontov was one of the most important poets and novelists. The first great Russian novelist was Nikolai Gogol. Then came Ivan Turgenev, who mastered both short stories and novels. Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy soon became internationally renowned. Other important figures of Russian realism were Ivan Goncharov, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin and Nikolai Leskov. In the second half of the century Anton Chekhov excelled in short stories and became a leading dramatist. The beginning of the 20th century ranks as the Silver Age of Russian poetry. The poets most often associated with the "Silver Age" are Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, Alexander Blok, Anna Akhmatova, Nikolay Gumilyov, Sergei Yesenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Marina Tsvetaeva. This era produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as Aleksandr Kuprin, Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, Leonid Andreyev, Fyodor Sologub, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Alexander Belyaev, Andrei Bely and Maxim Gorky.

Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin was the first Russian writer awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. He was noted for the strict artistry with which he carried on the classical Russian traditions in the writing of prose and poetry. The texture of his poems and stories, sometimes referred to as "Bunin brocade", is considered to be one of the richest in the language.

Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov was a Russian poet, prose writer, dramatist, translator, critic and historian. He was one of the principal members of the Russian Symbolist movement.

Zinaida Nikolayevna Gippius (Hippius) was a Russian poet, playwright, novelist, editor and religious thinker, one of the major figures in Russian symbolism. The story of her marriage to Dmitry Merezhkovsky, which lasted 52 years, is described in her unfinished book Dmitry Merezhkovsky.

Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont was a Russian symbolist poet and translator who became one of the major figures of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry.

Vadim Gabrielevich Shershenevich was a Russian poet. He was highly prolific, working in more than one genre, moving from Symbolism to Futurism after meeting Marinetti in Moscow. Later he pioneered the post-revolutionary avant-garde Imaginist movement, but abandoned it in favour of the theatre.

Mirra Lokhvitskaya was a Russian poet who rose to fame in the late 1890s. In her lifetime, she published five books of poetry, the first and the last of which received the prestigious Pushkin Prize. Due to the erotic sensuality of her works, Lokhvitskaya was regarded as the "Russian Sappho" by her contemporaries, which did not correspond with her conservative life style of dedicated wife and mother of five sons. Forgotten in Soviet times, in the late 20th century Lokhvitskaya's legacy was re-assessed and she came to be regarded as one of the most original and influential voices of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry and the first in the line of modern Russian women poets who paved the way for Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva.

Burning Buildings is the fifth book by Russian Silver Age modernist poet Konstantin Balmont. It was first published in 1900 by Scorpion in Moscow and made its author famous across his country.

Scorpion (Скорпион) was a Russian publishing house which played an important role in the development of Russian Symbolism in the early 1900s.

Fyodor Dmitrievich Batyushkov was a Russian philologist, editor, literary critic, theatre and literary historian.

Pyotr Petrovich Pertsov was a Russian poet, publisher, editor, literary critic, journalist and memoirist associated with the Russian Symbolist movement.

Novy Put was a Russian religious, philosophical and literary magazine, founded in 1902 in Saint Petersburg by Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Zinaida Gippius. Initially a literary vehicle for the Religious and Philosophical Meetings, it was aiming to promote the so-called "Godseeking" doctrine through the artistic means of Russian Symbolism.

Collection of Poems. 1889–1903 is the first book of poetry by Zinaida Gippius which collected 97 of her early poems. It was published in October 1903 by the Scorpion Publishing house.

Under the Northern Sky is a collection of poetry by Konstantin Balmont featuring 51 poems, first published in the early 1894 in Saint Petersburg. Formally Balmont's second book, it is considered to be his debut, since all the copies of the Yaroslavl-released Collection of Poems have been purchased and destroyed by the author.

In Boundlessness is a second major poetry collection by Konstantin Balmont, first published in 1895 in Moscow. Following Under the Northern Sky, it features 95 poems, some of which bear first signs of the author's experiments with the Russian language's musical and rhythmical structures he would later become famous for.

Evgeny Vasilyevich Anichkov was a Russian literary critic and historian who specialised in the Slavic folklore and mythology, as well as their relation to and use in the Russian literature.

Adelaida Gertsyk was a Russian translator, poet and writer of the Silver Age. Her literary salons of the 19th and early 20th century brought many of the poets of the age together. Almost forgotten after her lifetime, scholarship renewed on Gertsyk at the end of the Soviet era and she is now deemed one of the significant poets of her age.

Polyxena Solovyova was a Russian poet and illustrator. A Symbolist poet, from the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, she won the Medal of Pushkin in 1908. She was the first person to translate Alice in Wonderland into the Russian language and was known for founding and illustrating the magazine and publishing house Тропинка (Path) with her partner, Natalia Manaseina.