Francis Scott Key was an American lawyer, author, and poet from Frederick, Maryland, best known as the author of the text of the American national anthem "The Star-Spangled Banner". Key observed the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814 during the War of 1812. He was inspired upon seeing the American flag still flying over the fort at dawn and wrote the poem "Defence of Fort M'Henry"; it was published within a week with the suggested tune of the popular song "To Anacreon in Heaven". The song with Key's lyrics became known as "The Star-Spangled Banner" and slowly gained in popularity as an unofficial anthem, finally achieving official status as the national anthem more than a century later under President Herbert Hoover.

Benjamin Lundy was an American Quaker abolitionist from New Jersey of the United States who established several anti-slavery newspapers and traveled widely. He lectured and published seeking to limit slavery's expansion and tried to find a place outside the United States to establish a colony in which freed slaves might relocate.

Henry Highland Garnet was an American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. Having escaped as a child from slavery in Maryland with his family, he grew up in New York City. He was educated at the African Free School and other institutions, and became an advocate of militant abolitionism. He became a minister and based his drive for abolitionism in religion.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an 1845 memoir and treatise on abolition written by African-American orator and former slave Frederick Douglass during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts. It is generally held to be the most famous of a number of narratives written by former slaves during the same period. In factual detail, the text describes the events of his life and is considered to be one of the most influential pieces of literature to fuel the abolitionist movement of the early 19th century in the United States.

Samuel D. Burris was a member of the Underground Railroad. He had a family, who he moved to Philadelphia for safety and traveled into Maryland and Delaware to guide freedom seekers north along the Underground Railroad to Pennsylvania.

William J. Anderson was an American who wrote a narrative describing his life as a slave.

Leonard Black was born a slave in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, and was separated from his family by the age of six. He escaped after 20 years of slavery. In 1847 he wrote The Life and Sufferings of Leonard Black: A Fugitive from Slavery. With encouragement and support, he became a Baptist minister, preaching in Boston, Providence, and Nantucket before becoming minister of First Baptist Church in Petersburg, Virginia.

Charles Ball was an enslaved African-American from Maryland, best known for his account as a fugitive slave, Slavery in the United States (1836).

Solomon Bayley was a formerly enslaved African American who is best known for his 1825 autobiography entitled A Narrative of Some Remarkable Incidents in the Life of Solomon Bayley, Formerly a Slave in the State of Delaware, North America. Published in London, it is among the early slave narratives written by enslaved people who gained freedom before the American Civil War and emancipation. Bayley was born into slavery in Delaware. After escaping and being recaptured, he bought his freedom, including his wife and children. He worked as a farmer and at a sawmill. In their later years, he and his wife emigrated in 1827 to the new colony of Liberia, where he worked as a missionary and farmer. His short book about the colony was published in Delaware in 1833.

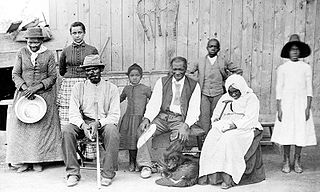

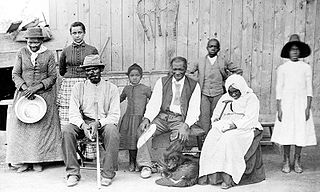

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. In 1830, enslaved African Americans represented 24 percent of Kentucky's population, a share that had declined to 19.5 percent by 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Most enslaved people were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington and in the hemp- and tobacco-producing Bluegrass Region and Jackson Purchase. Other enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties, where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Relatively few people were held in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky; they served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley was an American seamstress, activist, and writer who lived in Washington, D.C. She was the personal dressmaker and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln. She wrote an autobiography.

Bethany Veney, was an American writer whose autobiography and slave narrative, Aunt Betty's Story: The Narrative of Bethany Veney, A Slave Woman, was published in 1889. Born into slavery on a farm near Luray, Virginia, as Bethany Johnson, married twice, first to an enslaved man, Jerry Fickland, with whom she had a daughter, Charlotte. He was sold away from her and she later married Frank Veney, a free black man. She was sold on an auction block to her enslaver, George J. Adams, who brought her to Providence, Rhode Island, and later to Worcester, Massachusetts. After the American Civil War, Veney made four trips to Virginia to move her daughter and her family and 16 additional family members north to New England.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

The history of African Americans in Maryland is long and complex. Southern Maryland is the home of the first person of African descent to be elected to and serve in a legislature in America. His name was Mathias de Sousa and he was one of the original colonists to arrive in 1634. Southern Maryland is also the place where Josiah Henson was enslaved, and the place of brutality he wrote about in his later autobiography, which became the basis for Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin".

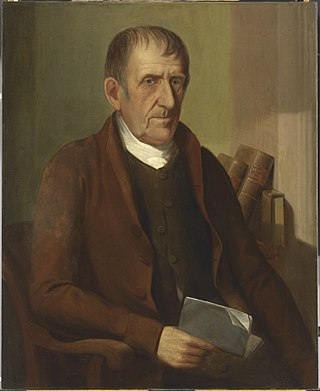

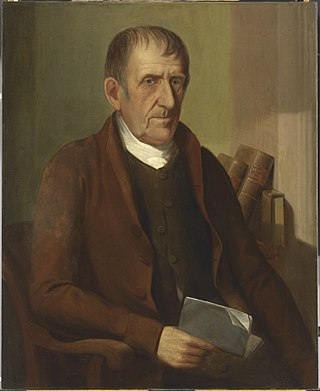

Elisha Tyson was an American colonial millionaire and philanthropist who was active in the abolition movement, Underground Railroad, and African colonization movement. He helped black people escape slavery by establishing safe houses, or Underground Railroad stations, on the route from Maryland to Pennsylvania. He purchased the freedom of blacks at slave auctions. He also initiated lawsuits for kidnapped blacks and created a group of vigilantes to prevent blacks from being kidnapped and enslaved. He also returned some kidnapped people from Liberia returned to their home country.

Margaret Morgan was an African American woman who was born to former slaves. They were considered free by their slaveholder, but they had not received an official deed of manumission. They lived on their former slaveholder's property, where they then had a daughter, Margaret. After she was married and had children, her family was taken from her home in the middle of the night around late March 1837 at the request of the former slaveholder's widow, Margaret Ashmore. Morgan became the subject of legal cases at the county, state and national level from 1837 to 1842. Prigg v. Pennsylvania was tried before the United States Supreme Court and the four men who apprehended Morgan and her children were found to be not guilty.

Harriet Tubman (1822 – 1913) was an American abolitionist and political activist. Tubman escaped slavery and rescued approximately 70 enslaved people, including members of her family and friends. Harriet Tubman's family includes her birth family; her two husbands, John Tubman and Nelson Davis; and her adopted daughter Gertie Davis.

Isaac S. Flint was an Underground Railroad station master, lecturer, farmer, and a teacher. He saved Samuel D. Burris, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, from being sold into slavery after having been caught helping runaway enslaved people.