Related Research Articles

AD 4 was a common year starting on Wednesday or a leap year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar and a leap year starting on Tuesday of the Proleptic Julian calendar. In the Roman Empire, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Catus and Saturninus. The denomination "AD 4" for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

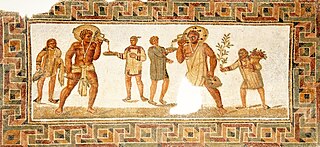

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that the most widely used term is gratuitous manumission, "the conferment of freedom on the enslaved by enslavers before the end of the slave system".

In ancient Rome, a gens was a family consisting of individuals who shared the same nomen gentilicium and who claimed descent from a common ancestor. A branch of gens, identified by the cognomen, was called a stirps. The gens was an important social structure at Rome and throughout Italia during the period of the Roman Republic. Much of individuals' social standing depended on the gens to which they belonged. Certain gentes were classified as patrician, others as plebeian; some had both patrician and plebeian branches. The importance of the gens as a social structure declined considerably in imperial times, although the gentilicium continued to define the origins and dynasties of the ancient Romans, including the Emperors.

Citizenship in ancient Rome was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cultural practices. There existed several different types of citizenship, determined by one's gender, class, and political affiliations, and the exact duties or expectations of a citizen varied throughout the history of the Roman Empire.

The Constitutio Antoniniana, also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution, was an edict issued in AD 212 by the Roman emperor Caracalla. It declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship.

Latin rights were a set of legal rights that were originally granted to the Latins under Roman law in their original territory and therefore in their colonies. Latinitas was commonly used by Roman jurists to denote this status. With the Roman expansion in Italy, many settlements and coloniae outside of Latium had Latin rights.

In Roman law, status describes a person's legal status. The individual could be a Roman citizen, unlike foreigners; or he could be free, unlike slaves; or he could have a certain position in a Roman family either as head of the family, or as a lower member.

The lex Fufia Caninia of 2 BC was a law passed under Augustus, the first Roman emperor, concerning the manumission of slaves. The law placed limits on the number of slaves that could be formally released from slavery by means of a will. Testamentary manumission had been established in early Rome as one of three procedures recognized in Roman law as not only granting libertas (liberty) to the formerly enslaved person but also full citizenship.

The Lex Aelia Sentia was a law established in the Roman Empire in 4 AD. It was one of the laws that the Roman assemblies passed at the behest of the emperor Augustus. Along with the Lex Fufia Caninia of 2 BC, this law regulated the manumission of slaves.

A lex Julia was an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the gens Julia. Most often, "Julian laws", lex Julia or leges Juliae refer to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 BC, or to a law related to Julius Caesar.

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Unskilled or low-skill slaves labored in the fields, mines, and mills with few opportunities for advancement and little chance of freedom. Skilled and educated slaves—including artisans, chefs, domestic staff and personal attendants, entertainers, business managers, accountants and bankers, educators at all levels, secretaries and librarians, civil servants, and physicians—occupied a more privileged tier of servitude and could hope to obtain freedom through one of several well-defined paths with protections under the law. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a distinguishing feature of Rome's system of slavery, resulting in a significant and influential number of freedpersons in Roman society.

Birth certificates for Roman citizens were introduced during the reign of Augustus. Until the time of Alexander Severus, it was required that these documents be written in Latin as a marker of "Romanness" (Romanitas).

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a peregrinus was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. Peregrini constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In AD 212, all free inhabitants of the Empire were granted citizenship by the Constitutio Antoniniana, with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves.

A fideicommissum is a type of bequest in which the beneficiary is encumbered to convey parts of the decedent's estate to someone else. For example, if a father leaves the family house to his firstborn, on condition that they will bequeath it to their first child. It was one of the most popular legal institutions in ancient Roman law for several centuries. The word is a conjunction of the Latin words fides (trust) and committere, and thus denotes that something is committed to one's trust.

Leges Clodiae were a series of laws (plebiscites) passed by the Plebeian Council of the Roman Republic under the tribune Publius Clodius Pulcher in 58 BC. Clodius was a member of the patrician family ("gens") Claudius; the alternative spelling of his name is sometimes regarded as a political gesture. With the support of Julius Caesar, who held his first consulship in 59 BC, Clodius had himself adopted into a plebeian family in order to qualify for the office of tribune of the plebs, which was not open to patricians. Clodius was famously a bitter opponent of Cicero.

In ancient Rome, the dediticii or peregrini dediticii were a class of free provincials who were neither slaves nor citizens holding either full Roman citizenship as cives or Latin rights as Latini.

Gaius Sentius Saturninus was a Roman senator, and consul ordinarius for AD 4 as the colleague of Sextus Aelius Catus. He was the middle son of Gaius Sentius Saturninus, consul in 19 BC. During his consulate the Lex Aelia Sentia, concerning the manumission of slaves, was published.

In ancient Rome, contubernium was a quasi-marital relationship between two slaves or between a slave (servus) and a free citizen who was usually a former slave or the child of a former slave. A slave involved in such a relationship was called contubernalis, the basic and general meaning of which was "companion".

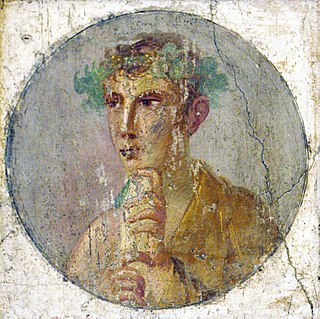

Freedmen in ancient Rome existed as a distinct social class (liberti), with former slaves granted freedom and rights through the legal process of manumission. The Roman practice of slavery utilized slaves for both production and domestic labour, overseen by their wealthy masters. Urban and domestic slaves especially could achieve high levels of education, acting as agents and representatives of their masters' affairs and finances. Within Roman law there was a set of practices for freeing trusted slaves, granting them a limited form of Roman citizenship or Latin rights. These freed slaves were known in Latin as liberti (freedmen), and formed a class set apart from freeborn Romans. While freedmen were barred from some forms of social mobility in Roman society, many achieved high levels of wealth and status. Liberti were an important part of the "most economically active and innovative entrepreneurial class" in the Roman Empire. The legal and social status of freedmen remained a point of cultural and legal contention throughout the Republic and Empire.

Inheritance law in ancient Rome was the Roman law that governed the inheritance of property. This law was governed by the civil law of the Twelve Tables and the laws passed by the Roman assemblies, which tended to be very strict, and law of the praetor, which was often more flexible. The resulting system was extremely complicated and was one of the central concerns of the whole legal system. Discussion of the laws of inheritance take up eleven of the fifty books in the Digest. 60-70% of all Roman litigation was concerned with inheritance.

References

- ↑ Nasmith, D.,Outline of Roman History from Romulus to Justinian (2006), p. 87

- ↑ Braund, D., Augustus to Nero (Routledge Revivals): A Sourcebook on Roman History, 31 BC-AD 68 (2015)

- ↑ Egbert Koops, "Masters and Freeden: Junian Latins and the Struggle for Citizenship," in Integration in Rome and in the Roman World: Proceedings of the Tenth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Lille, June 23-25, 2011) (Brill 2014), p. 114, especially n. 58.

- ↑ Marguerite Hirt, "In search of Junian Latins," Historia 67:3 (2018), p. 288, especially n. 2.

- ↑ Luigi Pellecchi, "The LegaL Foundation: The Leges Iunia et Aelia Sentia," in Junian Latinity in the Roman Empire. Vol. 1: History, Law, Literature, Edinburgh Studies in Ancient Slavery (Edinburgh University Press, 2023), pp. 60–64.

- ↑ Campbell, G., A Compendium of Roman Law (2008). p. 171

- ↑ William Smith, W., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

- ↑ The Enactments of Justinian, The Institutes, Bok 1, Title 5, Concerning freedmen, 3