A cement is a binder, a substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement mixed with fine aggregate produces mortar for masonry, or with sand and gravel, produces concrete. Concrete is the most widely used material in existence and is behind only water as the planet's most-consumed resource.

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "lime" connotes calcium-containing inorganic materials, in which carbonates, oxides and hydroxides of calcium, silicon, magnesium, aluminium, and iron predominate. By contrast, quicklime specifically applies to the single chemical compound calcium oxide. Calcium oxide that survives processing without reacting in building products such as cement is called free lime.

Mortar is a workable paste which hardens to bind building blocks such as stones, bricks, and concrete masonry units, to fill and seal the irregular gaps between them, spread the weight of them evenly, and sometimes to add decorative colors or patterns to masonry walls. In its broadest sense, mortar includes pitch, asphalt, and soft mud or clay, as used between mud bricks. The word "mortar" comes from Old French mortier, "builder's mortar, plaster; bowl for mixing." (13c.).

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "render" commonly refers to external applications. Another imprecise term used for the material is stucco, which is also often used for plasterwork that is worked in some way to produce relief decoration, rather than flat surfaces.

Drywall is a panel made of calcium sulfate dihydrate (gypsum), with or without additives, typically extruded between thick sheets of facer and backer paper, used in the construction of interior walls and ceilings. The plaster is mixed with fiber ; plasticizer, foaming agent; and additives that can reduce mildew, flammability, and water absorption.

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and artistic material in architecture. Stucco can be applied on construction materials such as metal, expanded metal lath, concrete, cinder block, or clay brick and adobe for decorative and structural purposes.

Lath and plaster is a building process used to finish mainly interior dividing walls and ceilings. It consists of narrow strips of wood (laths) which are nailed horizontally across the wall studs or ceiling joists and then coated in plaster. The technique derives from an earlier, more primitive, process called wattle and daub.

Lime is a calcium-containing inorganic mineral composed primarily of oxides, and hydroxide, usually calcium oxide and/or calcium hydroxide. It is also the name for calcium oxide which occurs as a product of coal-seam fires and in altered limestone xenoliths in volcanic ejecta. The word lime originates with its earliest use as building mortar and has the sense of sticking or adhering.

Hydraulic lime (HL) is a general term for calcium oxide, a variety of lime also called quicklime, that sets by hydration. This contrasts with calcium hydroxide, also called slaked lime or air lime that is used to make lime mortar, the other common type of lime mortar, which sets by carbonation (re-absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air). Hydraulic lime provides a faster initial set and higher compressive strength than air lime and hydraulic lime will set in more extreme conditions, including under water.

Lime plaster is a type of plaster composed of sand, water, and lime, usually non-hydraulic hydrated lime. Ancient lime plaster often contained horse hair for reinforcement and pozzolan additives to reduce the working time.

Plasterwork is construction or ornamentation done with plaster, such as a layer of plaster on an interior or exterior wall structure, or plaster decorative moldings on ceilings or walls. This is also sometimes called pargeting. The process of creating plasterwork, called plastering or rendering, has been used in building construction for centuries. For the art history of three-dimensional plaster, see stucco.

A plasterer is a tradesman who works with plaster, such as forming a layer of plaster on an interior wall or plaster decorative moldings on ceilings or walls. The process of creating plasterwork, called plastering, has been used in building construction for centuries. A plasterer is someone who does a full 4 or 2 years apprenticeship to be fully qualified

Metakaolin is the anhydrous calcined form of the clay mineral kaolinite. Minerals that are rich in kaolinite are known as china clay or kaolin, traditionally used in the manufacture of porcelain. The particle size of metakaolin is smaller than cement particles, but not as fine as silica fume.

Earthen plaster is a blend of clay, fine aggregate, and fiber. Other common additives include pigments, lime, casein, prickly pear cactus juice (Opuntia), manure, and linseed oil. Earthen plaster is usually applied to masonry, cob, or straw bale interiors or exteriors as a wall finish. It provides protection to the structural and insulating building components as well as texture and color.

Reed mat is lathing supplied in a roll. It is made from natural reeds laid parallel, and bound using zinc-plated narrow gauge wire to form a long sheet.

Wattle and daub is a composite building method used for making walls and buildings, in which a woven lattice of wooden strips called wattle is daubed with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, animal dung and straw. Wattle and daub has been used for at least 6,000 years and is still an important construction method in many parts of the world. Many historic buildings include wattle and daub construction.

Fly ash brick (FAB) is a building material, specifically masonry units, containing class C or class F fly ash and water. Compressed at 28 MPa(272 atm) and cured for 24 hours in a 66 °C steam bath, then toughened with an air entrainment agent, the bricks can last for more than 100 freeze-thaw cycles. Owing to the high concentration of calcium oxide in class C fly ash, the brick is described as "self-cementing". The manufacturing method saves energy, reduces mercury pollution in the environment, and often costs 20% less than traditional clay brick manufacturing.

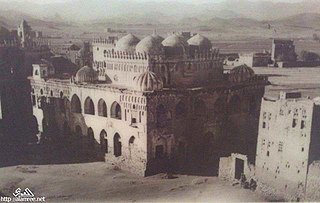

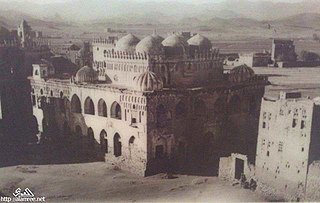

Qadad or qudad is a waterproof plaster surface, made of a lime plaster treated with slaked lime and oils and fats. The technique is over a thousand years old, with the remains of this early plaster still seen on the standing sluices of the ancient Marib Dam.

Sarooj is a traditional water-resistant mortar used in Iranian architecture, used in the construction of bridges, and yakhchal. It is made of clay and limestone mixed in a six-to-four ratio to make a stiff mix, and kneaded for two days. A portion of furnace slags from baths is combined with cattail (Typha) fibers, egg, and straw, and fixed, then beaten with a wooden stick for even mixing. Egg whites can be used as a water reducer as needed.

The Buxton lime industry has been important for the development of the town of Buxton in Derbyshire, England, and it has shaped the landscape around the town.