Related Research Articles

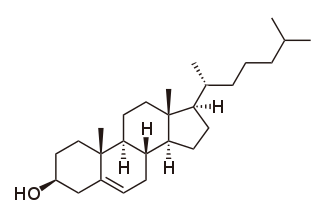

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules. A cholesterol is a sterol, a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell membranes. When chemically isolated, it is a yellowish crystalline solid.

In biology and biochemistry, a lipid is a macro biomolecule that is soluble in nonpolar solvents. Non-polar solvents are typically hydrocarbons used to dissolve other naturally occurring hydrocarbon lipid molecules that do not dissolve in water, including fatty acids, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins, monoglycerides, diglycerides, triglycerides, and phospholipids.

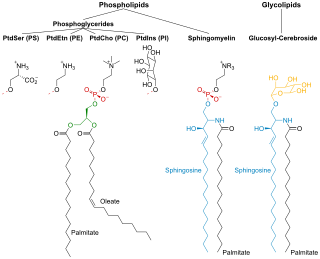

Phospholipids, also known as phosphatides, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue. Marine phospholipids typically have omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA integrated as part of the phospholipid molecule. The phosphate group can be modified with simple organic molecules such as choline, ethanolamine or serine.

A lipoprotein is a biochemical assembly whose primary function is to transport hydrophobic lipid molecules in water, as in blood plasma or other extracellular fluids. They consist of a triglyceride and cholesterol center, surrounded by a phospholipid outer shell, with the hydrophilic portions oriented outward toward the surrounding water and lipophilic portions oriented inward toward the lipid center. A special kind of protein, called apolipoprotein, is embedded in the outer shell, both stabilising the complex and giving it a functional identity that determines its role.

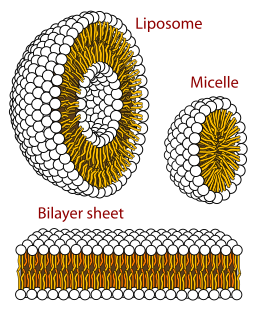

The lipid bilayer is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble (hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps.

The plasma membranes of cells contain combinations of glycosphingolipids, cholesterol and protein receptors organised in glycolipoprotein lipid microdomains termed lipid rafts. Their existence in cellular membranes remains somewhat controversial. It has been proposed that they are specialized membrane microdomains which compartmentalize cellular processes by serving as organising centers for the assembly of signaling molecules, allowing a closer interaction of protein receptors and their effectors to promote kinetically favorable interactions necessary for the signal transduction. Lipid rafts influence membrane fluidity and membrane protein trafficking, thereby regulating neurotransmission and receptor trafficking. Lipid rafts are more ordered and tightly packed than the surrounding bilayer, but float freely within the membrane bilayer. Although more common in the cell membrane, lipid rafts have also been reported in other parts of the cell, such as the Golgi apparatus and lysosomes.

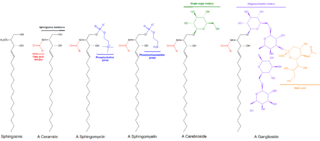

Sphingomyelin is a type of sphingolipid found in animal cell membranes, especially in the membranous myelin sheath that surrounds some nerve cell axons. It usually consists of phosphocholine and ceramide, or a phosphoethanolamine head group; therefore, sphingomyelins can also be classified as sphingophospholipids. In humans, SPH represents ~85% of all sphingolipids, and typically make up 10–20 mol % of plasma membrane lipids.

Cardiolipin is an important component of the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it constitutes about 20% of the total lipid composition. It can also be found in the membranes of most bacteria. The name "cardiolipin" is derived from the fact that it was first found in animal hearts. It was first isolated from beef heart in the early 1940s. In mammalian cells, but also in plant cells, cardiolipin (CL) is found almost exclusively in the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it is essential for the optimal function of numerous enzymes that are involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism.

In biology, membrane fluidity refers to the viscosity of the lipid bilayer of a cell membrane or a synthetic lipid membrane. Lipid packing can influence the fluidity of the membrane. Viscosity of the membrane can affect the rotation and diffusion of proteins and other bio-molecules within the membrane, there-by affecting the functions of these things.

Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) is a class of phospholipids found in biological membranes. They are synthesized by the addition of cytidine diphosphate-ethanolamine to diglycerides, releasing cytidine monophosphate. S-Adenosyl methionine can subsequently methylate the amine of phosphatidylethanolamines to yield phosphatidylcholines. It can mainly be found in the inner (cytoplasmic) leaflet of the lipid bilayer.

Membrane lipids are a group of compounds which form the double-layered surface of all cells. The three major classes of membrane lipids are phospholipids, glycolipids, and cholesterol. Lipids are amphiphilic: they have one end that is soluble in water ('polar') and an ending that is soluble in fat ('nonpolar'). By forming a double layer with the polar ends pointing outwards and the nonpolar ends pointing inwards membrane lipids can form a 'lipid bilayer' which keeps the watery interior of the cell separate from the watery exterior. The arrangements of lipids and various proteins, acting as receptors and channel pores in the membrane, control the entry and exit of other molecules and ions as part of the cell's metabolism. In order to perform physiological functions, membrane proteins are facilitated to rotate and diffuse laterally in two dimensional expanse of lipid bilayer by the presence of a shell of lipids closely attached to protein surface, called annular lipid shell.

Polymorphism in biophysics is the ability of lipids to aggregate in a variety of ways, giving rise to structures of different shapes, known as "phases". This can be in the form of sphere of lipid molecules (micelles), pairs of layers that face one another, a tubular arrangement (hexagonal), or various cubic phases. More complicated aggregations have also been observed, such as rhombohedral, tetragonal and orthorhombic phases.

Miscibility is the property of two substances to mix in all proportions, forming a homogeneous mixture. The term is most often applied to liquids but also applies to solids and gases. For example, water and ethanol are miscible because they mix in all proportions.

Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase is a transferase enzyme which converts phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to phosphatidylcholine (PC) in the liver. In humans it is encoded by the PEMT gene within the Smith–Magenis syndrome region on chromosome 17.

One property of a lipid bilayer is the relative mobility (fluidity) of the individual lipid molecules and how this mobility changes with temperature. This response is known as the phase behavior of the bilayer. Broadly, at a given temperature a lipid bilayer can exist in either a liquid or a solid phase. The solid phase is commonly referred to as a “gel” phase. All lipids have a characteristic temperature at which they undergo a transition (melt) from the gel to liquid phase. In both phases the lipid molecules are constrained to the two dimensional plane of the membrane, but in liquid phase bilayers the molecules diffuse freely within this plane. Thus, in a liquid bilayer a given lipid will rapidly exchange locations with its neighbor millions of times a second and will, through the process of a random walk, migrate over long distances.

In membrane biology, fusion is the process by which two initially distinct lipid bilayers merge their hydrophobic cores, resulting in one interconnected structure. If this fusion proceeds completely through both leaflets of both bilayers, an aqueous bridge is formed and the internal contents of the two structures can mix. Alternatively, if only one leaflet from each bilayer is involved in the fusion process, the bilayers are said to be hemifused. In hemifusion, the lipid constituents of the outer leaflet of the two bilayers can mix, but the inner leaflets remain distinct. The aqueous contents enclosed by each bilayer also remain separated.

The presence of ethanol can lead to the formations of non-lamellar phases also known as non-bilayer phases. Ethanol has been recognized as being an excellent solvent in an aqueous solution for inducing non-lamellar phases in phospholipids. The formation of non-lamellar phases in phospholipids is not completely understood, but it is significant that this amphiphilic molecule is capable of doing so. The formation of non-lamellar phases is significant in biomedical studies which include drug delivery, the transport of polar and non-polar ions using solvents capable of penetrating the biomembrane, increasing the elasticity of the biomembrane when it is being disrupted by unwanted substances and functioning as a channel or transporter of biomaterial.

Hydrophobic mismatch is the difference between the thicknesses of hydrophobic regions of a transmembrane protein and of the biological membrane it spans. In order to avoid unfavorable exposure of hydrophobic surfaces to water, the hydrophobic regions of transmembrane proteins are expected to have approximately the same thickness as the hydrophobic region of the surrounding lipid bilayer. Nevertheless, the same membrane protein can be encountered in bilayers of different thickness. In eukaryotic cells, the plasma membrane is thicker than the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum. Yet all proteins that are abundant in the plasma membrane are initially integrated into the endoplasmic reticulum upon synthesis on ribosomes. Transmembrane peptides or proteins and surrounding lipids can adapt to the hydrophobic mismatch by different means.

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates the interior of all cells from the outside environment and protects the cell from its environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of cells and organelles, being selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall and the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, as well as the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

Lamellar phase refers generally to packing of polar-headed long chain nonpolar-tail molecules in an environment of bulk polar liquid, as sheets of bilayers separated by bulk liquid. In biophysics, polar lipids pack as a liquid crystalline bilayer, with hydrophobic fatty acyl long chains directed inwardly and polar headgroups of lipids aligned on the outside in contact with water, as a 2-dimensional flat sheet surface. Under transmission electron microscope (TEM), after staining with polar headgroup reactive chemical osmium tetroxide, lamellar lipid phase appears as two thin parallel dark staining lines/sheets, constituted by aligned polar headgroups of lipids. 'Sandwiched' between these two parallel lines, there exists one thicker line/sheet of non-staining closely packed layer of long lipid fatty acyl chains. This TEM-appearance became famous as Robertson's unit membrane - the basis of all biological membranes, and structure of lipid bilayer in unilamellar liposomes. In multilamellar liposomes, many such lipid bilayer sheets are layered concentrically with water layers in between.

References

- Ipsen, J. H., G. Karlstrom, O. G. Mouritsen, H. Wennerstrom, and M. J. Zuckermann. 1987. Phase equilibria in the phosphatidylcholine-cholesterol system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 905:162–172.

- Huang TH, Lee CWB, Dasgupta SK, Blume A, Griffin RG. 1993. "A C-13 and H-2 Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance Study of Phosphatidylcholine Cholesterol Interactions - Characterization of Liquid-Gel Phases." Biochemistry 32(48):13277-13287

- Vist MR, Davis JH. 1990. "Phase-Equilibria of Cholesterol Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Mixtures - H-2 Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance and Differential Scanning Calorimetry." Biochemistry 29(2):451-464.