The Aldine Press was the printing office started by Aldus Manutius in 1494 in Venice, from which were issued the celebrated Aldine editions of the classics. The first book that was dated and printed under his name appeared in 1495.

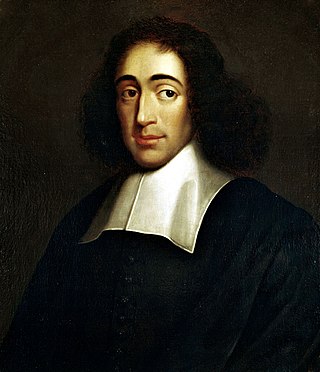

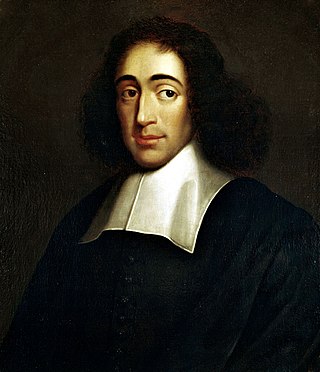

Baruch (de) Spinoza, also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin. As a forerunner of the Age of Reason, Spinoza significantly influenced modern biblical criticism, 17th-century Rationalism, and contemporary conceptions of the self and the universe, establishing himself as one of the most important and radical philosophers of the early modern period. He was influenced by Stoicism, Maimonides, Niccolò Machiavelli, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, and a variety of heterodox Christian thinkers of his day.

1632 (MDCXXXII) was a leap year starting on Thursday of the Gregorian calendar and a leap year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar, the 1632nd year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 632nd year of the 2nd millennium, the 32nd year of the 17th century, and the 3rd year of the 1630s decade. As of the start of 1632, the Gregorian calendar was 10 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which remained in localized use until 1923.

1677 (MDCLXXVII) was a common year starting on Friday of the Gregorian calendar and a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar, the 1677th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 677th year of the 2nd millennium, the 77th year of the 17th century, and the 8th year of the 1670s decade. As of the start of 1677, the Gregorian calendar was 10 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which remained in localized use until 1923.

Uriel da Costa was a Portuguese philosopher who was born a New Christian but returned to Judaism and ended up questioning the Catholic and rabbinic traditions of his time. This led him into conflict with both Christian and rabbinic institutions and caused his books to be included in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the List of Prohibited Books by the Catholic Church.

Pieter Burman, also known as Peter or Pieter Burmann and posthumously distinguished from his nephew as "the Elder", was a Dutch classical scholar.

Peter of Blois was a French cleric, theologian, poet and diplomat. He is particularly noted for his corpus of Latin letters.

Robert South was an English churchman who was known for his combative preaching and his Latin poetry.

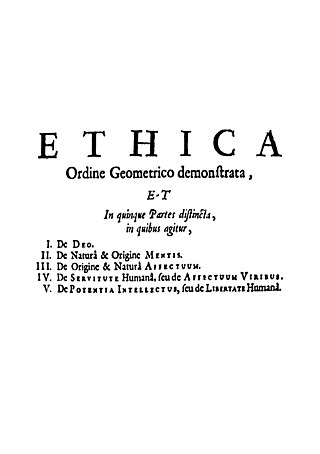

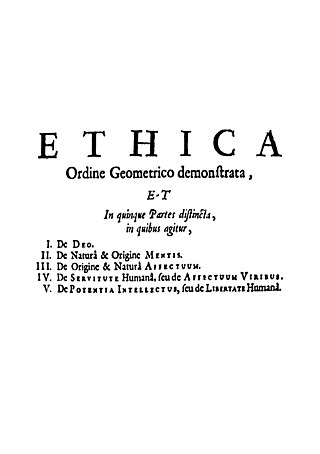

Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order, usually known as the Ethics, is a philosophical treatise written in Latin by Baruch Spinoza. It was written between 1661 and 1675 and was first published posthumously in 1677.

Petrus Serrarius was a millenarian theologian, writer, and also a wealthy merchant, who established himself in Amsterdam in 1630, and was active there until his death. He was born "into a well-to-do Walloon merchant family by name of Serrurier in London." He has been called "the dean of the dissident Millenarian theologians in Amsterdam".

Benedictus Buns, Benedictus à sancto Josepho, was a Carmelite priest and composer.

Theatrum Chemicum is a compendium of early alchemical writings published in six volumes over the course of six decades. The first three volumes were published in 1602, while the final sixth volume was published in its entirety in 1661. Theatrum Chemicum remains the most comprehensive collective work on the subject of alchemy ever published in the Western world.

Angelo Sabino or in Latin Angelus Sabinus was an Italian Renaissance humanist, poet laureate, classical philologist, Ovidian impersonator, and putative rogue.

Hadriaan Beverland was a Dutch humanist scholar who was banished from Holland in 1679 and settled in England in 1680.

Benedict is a masculine given name of Latin origin, meaning "blessed". Etymologically, it is derived from the Latin words bene ('good') and dicte ('speak'), i.e. "well spoken". The name was borne by Saint Benedict of Nursia (480–547), often called the founder of Western Christian monasticism.

Jan Hendriksz Glazemaker (1619/20–1682) was a Dutch translator of almost 70 books, mostly from Latin and from French. Glazemaker probably lived and worked in Amsterdam, where most of his translations were published. He may have been the first person in history to make a living primarily by translating into Dutch. While much of his output was of the Latin classics, he was particularly noted for his translations of the writings of René Descartes from both French and Latin, and for his translations of Spinoza's works from Latin.

The Epistolae are the correspondence of the Dutch philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza with a number of well-known learned men and with Spinoza's admirers, which Spinoza's followers in Amsterdam published after his death in the Opera Posthuma.

Johannes Bouwmeester was a Dutch physician, philosopher and a founding member of the literary society Nil volentibus arduum. He enrolled at Leiden University in 1651 and in 1658 graduated there in medicine. He was a close friend of Lodewijk Meyer, co-founder of Nil volentibus arduum, and acquainted with the philosophers Benedictus de Spinoza and Adriaen Koerbagh. His father, Claes Bouwmeester, was tailor by trade and several family members were builders of musical instruments. He was born in Amsterdam.