The Ides of March is the 74th day in the Roman calendar, corresponding to 15 March. It was marked by several religious observances and was notable for the Romans as a deadline for settling debts. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Cybele is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forerunner in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations. Phrygia's only known goddess, she was probably its national deity. Greek colonists in Asia Minor adopted and adapted her Phrygian cult and spread it to mainland Greece and to the more distant western Greek colonies around the 6th century BC.

Religion in ancient Rome includes the ancestral ethnic religion of the city of Rome that the Romans used to define themselves as a people, as well as the religious practices of peoples brought under Roman rule, in so far as they became widely followed in Rome and Italy. The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, and attributed their success as a world power to their collective piety (pietas) in maintaining good relations with the gods. The Romans are known for the great number of deities they honored, a capacity that earned the mockery of early Christian polemicists.

In the ancient Roman calendar, Quintilis or Quinctilis was the month following Junius (June) and preceding Sextilis (August). Quintilis is Latin for "fifth": it was the fifth month in the earliest calendar attributed to Romulus, which began with Martius and had 10 months. After the calendar reform that produced a 12-month year, Quintilis became the seventh month, but retained its name. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar instituted a new calendar that corrected astronomical discrepancies in the old. After his death in 44 BC, the month of Quintilis, his birth month, was renamed Julius in his honor, hence July.

Sextilis ("sixth") or mensis Sextilis was the Latin name for what was originally the sixth month in the Roman calendar, when March was the first of ten months in the year. After the calendar reform that produced a twelve-month year, Sextilis became the eighth month, but retained its name. It was renamed Augustus (August) in 8 BC in honor of the first Roman emperor, Augustus. Sextilis followed Quinctilis, which was renamed Julius (July) after Julius Caesar, and preceded September, which was originally the seventh month.

Februarius, fully Mensis Februarius, was the shortest month of the Roman calendar from which the Julian and Gregorian month of February derived. It was eventually placed second in order, preceded by Ianuarius and followed by Martius. In the oldest Roman calendar, which the Romans believed to have been instituted by their legendary founder Romulus, March was the first month, and the calendar year had only ten months in all. Ianuarius and Februarius were supposed to have been added by Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, originally at the end of the year. It is unclear when the Romans reset the course of the year so that January and February came first.

Sol Invictus was the official sun god of the later Roman Empire and a patron of soldiers. On 25 December AD 274, the Roman emperor Aurelian made it an official religion alongside the traditional Roman cults. Scholars disagree about whether the new deity was a refoundation of the ancient Latin cult of Sol, a revival of the cult of Elagabalus, or completely new. The god was favored by emperors after Aurelian and appeared on their coins until the last third-part of the reign of Constantine I. The last inscription referring to Sol Invictus dates to AD 387, and there were enough devotees in the fifth century that the Christian theologian Augustine found it necessary to preach against them.

Ianuarius, fully Mensis Ianuarius, was the first month of the ancient Roman calendar, from which the Julian and Gregorian month of January derived. It was followed by Februarius ("February"). In the calendars of the Roman Republic, Ianuarius had 29 days. Two days were added when the calendar was reformed under Julius Caesar in 45 BCE.

Maius or mensis Maius (May) was the third month of the ancient Roman calendar, following Aprilis (April) and preceding Iunius (June). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, it was the third of ten months in the year. May had 31 days.

Jörg Rüpke is a German scholar of comparative religion and classical philology, recipient of the Prix Gay Lussac-Humboldt in 2008, and of the Advanced Grant of the European Research Council in 2011. In January 2012, Rüpke was appointed by German Federal President Christian Wulff to the German Council of Science and Humanities.

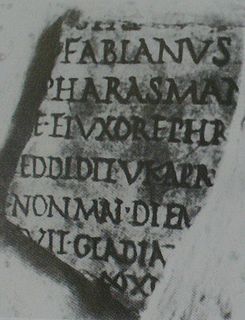

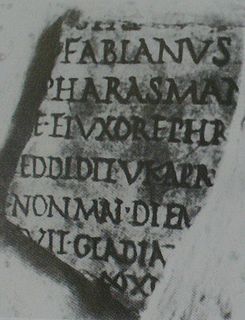

The Fasti Ostienses are a calendar of Roman magistrates and significant events from 49 BC to AD 175, found at Ostia, the principal seaport of Rome. Together with similar inscriptions, such as the Fasti Capitolini and Fasti Triumphales at Rome, the Fasti Ostienses form part of a chronology known as the Fasti Consulares, or Consular Fasti.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Hercules was venerated as a divinized hero and incorporated into the legends of Rome's founding. The Romans adapted Greek myths and the iconography of Heracles into their own literature and art, but the hero developed distinctly Roman characteristics. Some Greek sources as early as the 6th and 5th century BC gave Heracles Roman connections during his famous labors.

Martius or mensis Martius ("March") was the first month of the ancient Roman year until possibly as late as 153 BC. After that time, it was the third month, following Februarius (February) and preceding Aprilis (April). Martius was one of the few Roman months named for a deity, Mars, who was regarded as an ancestor of the Roman people through his sons Romulus and Remus.

Aprilis or mensis Aprilis (April) was the fourth month of the ancient Roman calendar, following Martius (March) and preceding Maius (May). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, Aprilis was the second of ten months in the year. April had 30 days on calendars of the Roman Republic, with a day added to the month during the reform in the mid-40s BC that produced the Julian calendar.

In the Roman Empire, Rosalia or Rosaria was a festival of roses celebrated on various dates, primarily in May, but scattered through mid-July. The observance is sometimes called a rosatio ("rose-adornment") or the dies rosationis, "day of rose-adornment," and could be celebrated also with violets (violatio, an adorning with violets, also dies violae or dies violationis, "day of the violet[-adornment]"). As a commemoration of the dead, the rosatio developed from the custom of placing flowers at burial sites. It was among the extensive private religious practices by means of which the Romans cared for their dead, reflecting the value placed on tradition (mos maiorum, "the way of the ancestors"), family lineage, and memorials ranging from simple inscriptions to grand public works. Several dates on the Roman calendar were set aside as public holidays or memorial days devoted to the dead.

In the Roman Empire, the Lychnapsia was a festival of lamps on August 12, widely regarded by scholars as having been held in honor of Isis. It was thus one of several official Roman holidays and observances that publicly linked the cult of Isis with Imperial cult. It is thought to be a Roman adaptation of Egyptian religious ceremonies celebrating the birthday of Isis. By the 4th century, Isiac cult was thoroughly integrated into traditional Roman religious practice, but evidence that Isis was honored by the Lychnapsia is indirect, and lychnapsia is a general word in Greek for festive lamp-lighting. In the 5th century, lychnapsia could be synonymous with lychnikon as a Christian liturgical office.

September or mensis September was originally the seventh of ten months on the ancient Roman calendar that began with March. It had 29 days. After the reforms that resulted in a 12-month year, September became the ninth month, but retained its name. September followed what was originally Sextilis, the "sixth" month, renamed Augustus in honor of the first Roman emperor, and preceded October, the "eighth" month that like September retained its numerical name contrary to its position on the calendar. A day was added to September in the mid-40s BC as part of the Julian calendar reform.

October or mensis October was the eighth of ten months on the oldest Roman calendar. It had 31 days. October followed September and preceded November. After the calendar reform that resulted in a 12-month year, October became the tenth month, but retained its numerical name, as did the other months from September to December.

November or mensis November was originally the ninth of ten months on the Roman calendar, following October and preceding December. It had 29 days. In the reform that resulted in a 12-month year, November became the eleventh month, but retained its name, as did the other months from September through December. A day was added to November during the Julian calendar reform in the mid-40s BC.

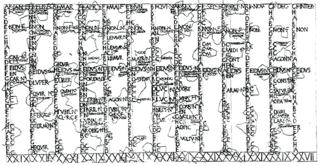

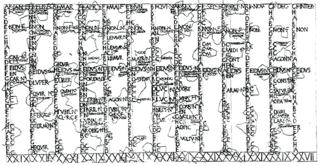

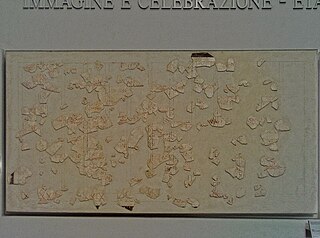

The Fasti Antiates Maiores is a painted wall-calendar from the late Roman Republic, the oldest archaeologically attested local Roman calendar and the only such calendar known from before the Julian calendar reforms. It was created between 84 and 55 BC and discovered in 1915 at Anzio, the ancient Antium, in a crypt next to the coast. It is now located in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome, part of the Museo Nazionale Romano, while a reconstruction of it is in the Museo del Teatro de Caesaragusta in Zaragoza, Spain.