The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war to resolve "disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them". The pact was signed by Germany, France, and the United States on 27 August 1928, and by most other states soon after. Sponsored by France and the U.S., the Pact is named after its authors, United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The pact was concluded outside the League of Nations and remains in effect.

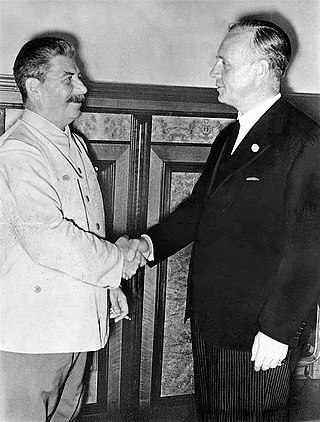

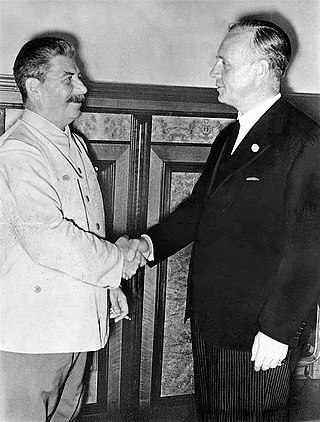

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, with a secret protocol establishing Soviet and German spheres of influence across Eastern Europe. The pact was signed in Moscow on 24 August 1939 by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Frank Billings Kellogg was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served in the U.S. Senate and as U.S. Secretary of State. He co-authored the Kellogg–Briand Pact, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1929.

The Treaty of Berlin was a treaty signed on 24 April 1926 under which Germany and the Soviet Union pledged neutrality in the event of an attack on the other by a third party for five years. The treaty reaffirmed the German-Soviet Treaty of Rapallo (1922).

The Locarno Treaties were seven post-World War I agreements negotiated amongst Germany, France, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, Poland and Czechoslovakia in late 1925. In the main treaty, the five western European nations pledged to guarantee the inviolability of the borders between Germany and France and Germany and Belgium as defined in the Treaty of Versailles. They also promised to observe the demilitarized zone of the German Rhineland and to resolve differences peacefully under the auspices of the League of Nations. In the additional arbitration treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia, Germany agreed to the peaceful settlement of disputes, but there was notably no guarantee of its eastern border, leaving the path open for Germany to attempt to revise the Versailles Treaty and regain territory it had lost in the east under its terms.

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Comintern). It was signed by German ambassador-at-large Joachim von Ribbentrop and Japanese ambassador to Germany Kintomo Mushanokōji. Italy joined in 1937, but it was legally recognized as an original signatory by the terms of its entry. Spain and Hungary joined in 1939. Other countries joined during World War II.

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat who served as People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs from 1930 to 1939.

German–Soviet Union relations date to the aftermath of the First World War. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, dictated by Germany ended hostilities between Russia and Germany; it was signed on March 3, 1918. A few months later, the German ambassador to Moscow, Wilhelm von Mirbach, was shot dead by Russian Left Socialist-Revolutionaries in an attempt to incite a new war between Russia and Germany. The entire Soviet embassy under Adolph Joffe was deported from Germany on November 6, 1918, for their active support of the German Revolution. Karl Radek also illegally supported communist subversive activities in Weimar Germany in 1919.

This timeline of events preceding World War II covers the events that affected or led to World War II.

The Franco-Polish Alliance was the military alliance between Poland and France that was active between the early 1920s and the outbreak of the Second World War. The initial agreements were signed in February 1921 and formally took effect in 1923. During the interwar period the alliance with Poland was one of the cornerstones of French foreign policy.

The German–Polish declaration of non-aggression, also known as the German–Polish non-aggression pact, was an agreement between Nazi Germany and the Second Polish Republic that was signed on 26 January 1934 in Berlin. Both countries pledged to resolve their problems by bilateral negotiations and to forgo armed conflict for a period of 10 years. The agreement effectively normalised relations between Poland and Germany, which had been strained by border disputes arising from the territorial settlement in the Treaty of Versailles. The declaration marked an end to an economically damaging customs war between the two countries that had taken place over the previous decade.

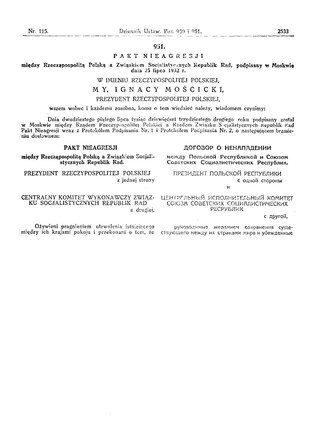

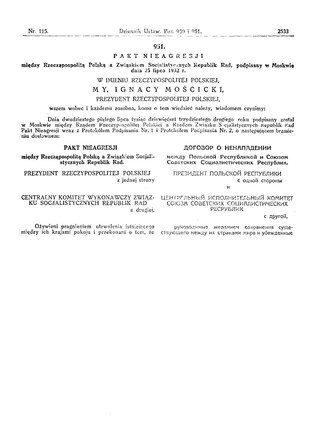

The Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact was a non-aggression pact signed in 1932 by representatives of Poland and the Soviet Union. The pact was unilaterally broken by the Soviet Union on September 17, 1939, during the Soviet invasion of Poland.

Between 28 June and 3 July 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, following an ultimatum made to Romania on 26 June 1940 that threatened the use of force. Those regions, with a total area of 50,762 km2 (19,599 sq mi) and a population of 3,776,309 inhabitants, were incorporated into the Soviet Union. On 26 October 1940, six Romanian islands on the Chilia branch of the Danube, with an area of 23.75 km2 (9.17 sq mi), were also occupied by the Soviet Army.

The Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1940 refers to the military occupation of the Republic of Latvia by the Soviet Union under the provisions of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany and its Secret Additional Protocol signed in August 1939.

The Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance was a bilateral treaty between France and the Soviet Union with the aim of enveloping Nazi Germany in 1935 to reduce the threat from Central Europe. It was pursued by Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreign minister, and Louis Barthou, the French foreign minister, who was assassinated in October 1934, before negotiations had been finished.

The Anglo-Soviet Agreement was a declaration signed by the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union on 12 July 1941, shortly after the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. In the agreement, the UK and the Soviet Union pledged to cooperate in the war against Nazi Germany and not to make a separate peace with Germany.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was an August 23, 1939, agreement between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany colloquially named after Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. The treaty renounced warfare between the two countries. In addition to stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included a secret protocol dividing several eastern European countries between the parties.

Relevant events began regarding the Baltic states and the Soviet Union when, following Bolshevist Russia's conflict with the Baltic states—Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia—several peace treaties were signed with Russia and its successor, the Soviet Union. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviet Union and all three Baltic States further signed non-aggression treaties. The Soviet Union also confirmed that it would adhere to the Kellogg–Briand Pact with regard to its neighbors, including Estonia and Latvia, and entered into a convention defining "aggression" that included all three Baltic countries.

The Seventh World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) was a multinational conference held in Moscow from July 25 through August 20, 1935 by delegated representatives of ruling and non-ruling communist parties from around the world and invited guests representing other political and organized labor organizations. The gathering was attended by 513 delegates, of whom 371 were accorded full voting rights, representing 65 Comintern member parties as well as 19 sympathizing parties.

Peace in Their Time: The Origins of the Kellogg-Briand Pact is a 1952 book by historian Robert H. Ferrell tracing the diplomatic, political and cultural events in the aftermath of World War I which led to the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928, an international agreement to end war as a means of settling disputes among nations. Ferrell's first book, Peace in Their Time elaborates on and extends Ferrell's 1951 Ph.D. dissertation, The United States and the Origins of the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which won Yale's John Addison Porter Prize for original scholarship. Peace In Their Time itself went on to win the American Historical Association's 1952 George Louis Beer Prize for outstanding historical writing. Ferrell would go on to become a professor at Indiana University and one of the most prominent historians in America, and wrote or edited more than 60 other books on historical topics. Historian Lawrence Kaplan praised Peace in Their Time as a harbinger of the high quality of Ferrell's subsequent career, stating that it "contained the special qualities that animated all his future work."