Lorch Abbey (German : Kloster Lorch) was a Benedictine monastery in Lorch from 1102 to 1556 and again from 1630 to 1648. It was originally the house monastery of the Staufer dynasty. Today, many of its buildings remain and are open to visitors.

Lorch Abbey (German : Kloster Lorch) was a Benedictine monastery in Lorch from 1102 to 1556 and again from 1630 to 1648. It was originally the house monastery of the Staufer dynasty. Today, many of its buildings remain and are open to visitors.

Lorch was founded in 1102 by Duke Frederick I of Swabia; his wife, Agnes of Waiblingen; and their sons, the future Duke Frederick II and King Conrad III. [1] [2] Its original buildings were completed by 1108 atop the Liebfrauenberg (Mountain of the Virgin). [1] It lay on allodial property a few miles north of Hohenstaufen Castle on the other side of the river Rems. [2] It at first served as a private church of the Staufer dynasty. [1] In 1136, it was donated to the papacy and accepted by Pope Innocent II. [2]

In 1139, Duke Frederick II was elected advocatus by the monks. He was then appointed by his brother, King Conrad III, who ruled that the head of the dynasty would thenceforth always be elected advocatus. In 1154, Frederick II's son, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, clarified that it was the eldest descendant of Frederick II and Conrad III who would always be advocatus. [2] It was probably around 1139 that Conrad III moved Frederick I's remains to the abbey for reburial. [2] Many members of the Staufer family were buried at Lorch after 1140. The exact number and identity of burials is unknown. [1] Conrad III desired to be buried there but was not. [2]

After the death of Conradin in 1268, Lorch was acquired by the County of Württemberg. [1] From the 13th century, the lords of Woellwarth endowed a chapel olding a purported relic of the skull of Saint Maurice. [3] As a result, in the 15th and 16th centuries, they had the right to be buried in the chapel. [1] [3] In 1475, Abbot Nikolaus Schenk von Arberg opened the Staufer tombs and gathered the bones into a single new richly carved sarcophagus and placed it in the nave. [3]

In the early 16th century, Lorch produced five illuminated choirbooks. The work was financed by Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, and his wife, Sabina of Bavaria. Only three of the Lorch choir books still survive today. They indicate that Lorch was part of the Melk Reform. [3]

Lorch was damaged on 26 April 1525 during the German Peasants' War. [1] [3] The damage was never repaired. The monastery was closed during the Reformation in 1556. [3] During the Thirty Years' War, it was briefly restored as a Catholic house under the Abbey of Saint Blaise in 1630. It was closed again with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. [4]

Plans to demolish the remains of the monastery were halted in the late 19th century, when it came to be seen as a monument to the Staufer. Today, it is operated by Baden-Württemberg's State Palaces and Gardens and is open to visitors. [3]

Lorch was a fortified monastery, surrounded by a rampart and stone wall with round towers. The wall as it still stands was built in the 13th century to expand the area of the monastery. It was renovated in the early 16th century. The eastern gate once had a tower, gatehouses and a moat with a drawbridge. [3] The buildings were originally built in the Romanesque style. [1]

The largest building was the cruciform church, which mostly still stands. [3] Its altar was dedicated to Saint Peter in 1139. [1] [3] It had two round towers on its west façade. Only the Marsilius tower remains. [3] Originally Romanesque, the church received a Gothic renovation in 1469 under Abbot Nikolaus Schenk von Arberg. [1] [3] Around 1500, the church had twelve altars. Once richly decorated, its decor has now been totally removed. [3] This includes once sizeable relic collection. The eight piers of the nave are decorated with paintings of the Staufer kings from around 1500. [1] The last of the church's furnishings, such as choir stalls, were taken out in 1833–1838, leaving an empty interior. [3]

The monks' residence, the cloister, was attached to the church. Only its north wing survives, the rest a victim of the Peasants' War. It is now known as the "prelature" and includes the former dormitory, chapter house and refectory. There are murals of the life of Christ from about 1530 in the refectory. A modern mural depicting the sweep of Staufer history was added by Hans Kloss to the chapter house. The half-timber abbot's house, a separate building which also served as a guesthouse, still stands. The bailiwick, the residence of the steward and later used by the dukes of Württemberg during hunting trips, has been torn down. [3]

The monastery's outbuildings included a hospital, school, cavalier house and tithe barns. The latter still stand, but the hospital and school are known only through archaeological excavations. A herb garden is still maintained at the site. [3]

Known or suspected Staufer burials at Lorch include:

The Staufer were remembered annually by the monks on September 2. [3]

In addition, the tombs of the abbots were also in the abbey. There are many surviving tomb slabs, some richly decorated. Some of the Woellwarth tomb slabs are also preserved. [3]

Lorch had 25 recorded Catholic abbots and one administrator. Their dates of tenure are often uncertain. [4]

The Hohenstaufen dynasty, also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynasty's most prominent rulers – Frederick I (1155), Henry VI (1191) and Frederick II (1220) – ascended the imperial throne and also reigned over Italy and Burgundy. The non-contemporary name of 'Hohenstaufen' is derived from the family's Hohenstaufen Castle on Hohenstaufen mountain at the northern fringes of the Swabian Jura, near the town of Göppingen. Under Hohenstaufen rule, the Holy Roman Empire reached its greatest territorial extent from 1155 to 1268.

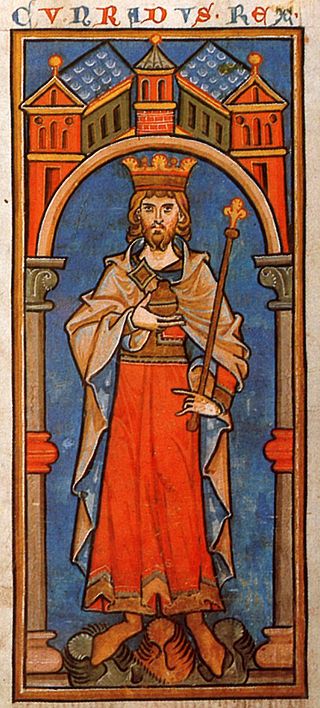

Conrad III of the Hohenstaufen dynasty was from 1116 to 1120 Duke of Franconia, from 1127 to 1135 anti-king of his predecessor Lothair III, and from 1138 until his death in 1152 King of the Romans in the Holy Roman Empire. He was the son of Duke Frederick I of Swabia and Agnes, a daughter of Emperor Henry IV.

Frederick I before 21 July was Duke of Swabia from 1079 to his death, the first ruler from the House of Hohenstaufen (Staufer).

Frederick II, called the One-Eyed, was Duke of Swabia from 1105 until his death, the second from the Hohenstaufen dynasty. His younger brother Conrad was elected King of the Romans in 1138.

Frederick V of Hohenstaufen was Duke of Swabia from 1167 to his death. He was the eldest son of Frederick I Barbarossa and Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy.

Frederick VI of Hohenstaufen was Duke of Swabia from 1170 until his death at the siege of Acre.

Conrad II, was Duke of Rothenburg (1188–1191) and Swabia from 1191 until his death. He was the fifth son of Frederick I Barbarossa and Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy.

Henry II, called Jasomirgott, a member of the House of Babenberg, was Count Palatine of the Rhine from 1140 to 1141, Duke of Bavaria and Margrave of Austria from 1141 to 1156, and the first Duke of Austria from 1156 until his death.

Agnes of Waiblingen, also known as Agnes of Germany, Agnes of Franconia and Agnes of Saarbrücken, was a member of the Salian imperial family. Through her first marriage, she was Duchess of Swabia; through her second marriage, she was Margravine of Austria.

Henry IX, was a member of the House of Welf, a powerful dynasty in medieval Germany. He was born around 1075 and died in 1126. Henry IX is often referred to as “Henry the Black” and ruled as Duke of Bavaria from 1120 until his death in 1126.

Maulbronn Monastery is a former Cistercian abbey and ecclesiastical state in the Holy Roman Empire located at Maulbronn, Baden-Württemberg. The monastery complex, one of the best-preserved in Europe, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993.

Hirsau Abbey, formerly known as Hirschau Abbey, was once one of the most important Benedictine abbeys of Germany. It is located in the Hirsau borough of Calw on the northern slopes of the Black Forest mountain range, in the present-day state of Baden-Württemberg. In the 11th and 12th century, the monastery was a centre of the Cluniac Reforms, implemented as "Hirsau Reforms" in the German lands by William of Hirsau. The complex was devastated during the War of the Palatine Succession in 1692 and not rebuilt. The ruins served as a quarry for a period of time.

Lorch is a small town in the Ostalbkreis district, in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, by the river Rems, 8 kilometers west of Schwäbisch Gmünd. It is a part of the Ostwürttemberg region.

St. George's Abbey in the Black Forest was a Benedictine monastery in St. Georgen im Schwarzwald in the southern Black Forest in Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Gengenbach Abbey was a Benedictine monastery in Gengenbach in the district of Ortenau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was an Imperial Abbey from the late Carolingian period to 1803.

Salem Abbey was a very prominent Cistercian monastery at Salem in the district of Bodensee, about ten miles from Konstanz in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The buildings are now owned by the State of Baden-Württemberg and are open for tours as the Salem Monastery and Palace.

Adelaide of Vohburg was Duchess of Swabia from 1147 and German queen from 1152 until 1153, as the first wife of the Hohenstaufen king Frederick Barbarossa, the later Holy Roman Emperor.

Rot an der Rot Abbey was a Premonstratensian monastery in Rot an der Rot in Upper Swabia, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was the first Premonstratensian monastery in the whole of Swabia. The imposing structure of the former monastery is situated on a hill between the valleys of the rivers Rot and Haslach. The monastery church, dedicated to St Verena, and the convent buildings are an important part of the Upper Swabian Baroque Route. Apart from the actual monastic buildings, a number of other structures have been preserved among which are the gates and the economy building.

Godfrey of Namur was a Lotharingian nobleman. He was Count jure uxoris of Porcéan from 1097 until his death. From 1102, he was also Count of Namur. He was the oldest son of Count Albert III and his wife Ida of Saxony, the heiress of Laroche.