Lise Meitner was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working on radioactivity at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Chemistry in Berlin, she discovered the radioactive isotope protactinium-231 in 1917. In 1938, Meitner and her nephew, the physicist Otto Robert Frisch, discovered nuclear fission. She was praised by Albert Einstein as the "German Marie Curie".

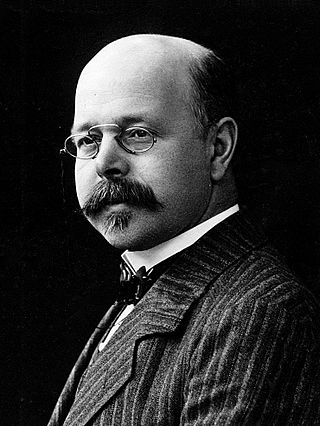

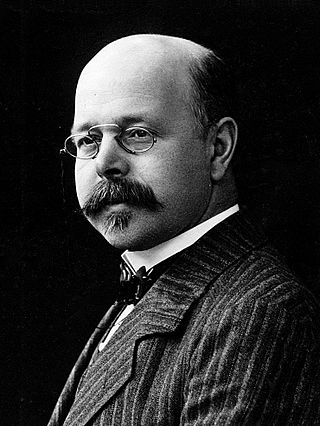

Walther Hermann Nernst was a German physicist and physical chemist known for his work in thermodynamics, physical chemistry, electrochemistry, and solid state physics. His formulation of the Nernst heat theorem helped pave the way for the third law of thermodynamics, for which he won the 1920 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He is also known for developing the Nernst equation in 1887.

Louis Carl Heinrich Friedrich Paschen, was a German physicist, known for his work on electrical discharges. He is also known for the Paschen series, a series of hydrogen spectral lines in the infrared region that he first observed in 1908. He established the now widely used Paschen curve in his article "Über die zum Funkenübergang in Luft, Wasserstoff und Kohlensäure bei verschiedenen Drücken erforderliche Potentialdifferenz". He is known for the Paschen-Back effect, which is the Zeeman effect's becoming non-linear at high magnetic field. He helped explain the hollow cathode effect in 1916.

The names Uranverein or Uranprojekt came to be applied in Nazi Germany to the undertakings of research in nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, before and during World War II. The first effort started in April 1939, just months after the discovery of nuclear fission in Berlin in December 1938, but ended only few months later, shortly ahead of the September 1939 German invasion of Poland, for which many notable German physicists were drafted into the Wehrmacht. A second effort under the administrative purview of the Wehrmacht's Heereswaffenamt began on September 1, 1939, the day of the invasion of Poland. The program eventually expanded into three main efforts: Uranmaschine, production of uranium and heavy water, and uranium isotope separation. Eventually, the German military assessed that nuclear fission would not contribute significantly to the war, and in January 1942 the Heereswaffenamt turned the program over to the Reich Research Council while still continuing to fund the activity.

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key piece of evidence necessary to identify the previously unknown phenomenon of nuclear fission, as was subsequently recognized and published by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch. In their second publication on nuclear fission in February of 1939, Strassmann and Hahn predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutrons during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.

Max Volmer was a German physical chemist, who made important contributions in electrochemistry, in particular on electrode kinetics. He co-developed the Butler–Volmer equation. Volmer held the chair and directorship of the Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry Institute of the Technische Hochschule Berlin, in Berlin-Charlottenburg. After World War II, he went to the Soviet Union, where he headed a design bureau for the production of heavy water. Upon his return to East Germany ten years later, he became a professor at the Humboldt University of Berlin and was president of the East German Academy of Sciences.

Max Ernst August Bodenstein was a German physical chemist known for his work in chemical kinetics. He was first to postulate a chain reaction mechanism and that explosions are branched chain reactions, later applied to the atomic bomb.

Siegfried Flügge was a German theoretical physicist who made contributions to nuclear physics and the theoretical basis for nuclear weapons. He worked on the German nuclear energy project. From 1941 onward he was a lecturer at several German universities, and from 1956 to 1984, editor of the 54-volume, prestigious Handbuch der Physik.

Arnold Rudolf Karl Flammersfeld was a German nuclear physicist who worked on the German nuclear energy project during World War II. From 1954, he was a professor of physics at the University of Göttingen.

Wilhelm Hanle was a German experimental physicist. He is known for the Hanle effect. During World War II, he made contributions to the German nuclear energy project, also known as the Uranium Club. From 1941 until emeritus status in 1969, he was an ordinarius professor of experimental physics and held the chair of physics at the University of Giessen.

Gerhard Hoffmann was a German nuclear physicist. During World War II, he contributed to the German nuclear energy project, also known as the Uranium Club.

Klaus Paul Alfred Clusius was a German physical chemist from Breslau (Wrocław), Silesia. During World War II, he worked on the German nuclear energy project, also known as the Uranium Club; he worked on isotope separation techniques and heavy water production. After the war, he was a professor of physical chemistry at the University of Zurich. He died in Zurich.

Gottfried Freiherr von Droste (1908–1992), a.k.a. Gottfried Freiherr von Droste zu Vischering-Padberg, was a German physical chemist. He worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (KWIC). He independently predicted that nuclear fission would release a large amount of energy. During World War II, he participated in the German nuclear energy project, also known as the Uranverein. In the latter years of the war, he worked at the Reich's University of Strassburg. After the war, he worked at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (Federal Physical and Technical Institute and also held a position at the Technical University of Braunschweig.

Wilhelm Orthmann was a German physicist. He was director of the physico-technical department of the Industrial College of Berlin. During World War II, he was also employed by the Reich Aviation Ministry.

Ernst Hermann Riesenfeld was a German/Swedish chemist. Riesenfeld started his academic career with important contributions in electrochemistry by the side of his mentor Walther Nernst, and continued as a professor with work on the improvement of analytical techniques and the purification of ozone. Dismissed and prosecuted in Nazi Germany due to his Jewish origins, he emigrated to Sweden in 1934 and continued his ozone-related work there until retirement.

Michael Diers is a German art historian and professor of art history in Hamburg and Berlin.

Luise Holzapfel was a German chemist and later head of department of the Kaiser Wilhelm/Max Planck Institute for Silicate Research. She is known for her research on silicosis.

Paula Hertwig was a German biologist and politician. Her research focused on radiation health effects. Hertwig was the first woman to habilitate at the then Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin in the field of zoology. She was also the first biologist at a German university. Hertwig is one of the founders of radiation genetics alongside Emmy Stein. Hertwig-Weyers syndrome, which describes oligodactyly in humans as a result of radiation exposure, is named after her and her colleague, Helmut Weyers.

Ursula Püschel was a German literary critic, journalist and writer. One focus of her activities was the work of the writer Bettina von Arnim, a representative of the Vormärz-Literatur.

Ellen Lax was a German industrial physicist who became known through the publication of the three-volume reference work Taschenbuch für Chemiker und Physiker together with Jean D'Ans. The first volume appeared in 1943, and to this day the so-called "D'Ans-Lax" is widely used as a reference for laboratory work. She also worked on the Landolt-Börnstein table.