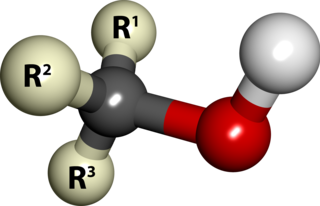

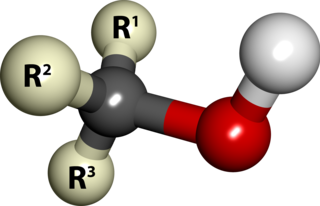

In chemistry, an alcohol is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl functional group bound to carbon. Alcohols range from the simple, like methanol and ethanol, to complex, like sugars and cholesterol. The presence of an OH group strongly modifies the properties of hydrocarbons, conferring hydrophilic (water-loving) properties. The OH group provides a site at which many reactions can occur.

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is often written as R−COOH or R−CO2H, sometimes as R−C(O)OH with R referring to an organyl group, or hydrogen, or other groups. Carboxylic acids occur widely. Important examples include the amino acids and fatty acids. Deprotonation of a carboxylic acid gives a carboxylate anion.

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom bonded to two organyl groups. They have the general formula R−O−R′, where R and R′ represent the organyl groups. Ethers can again be classified into two varieties: if the organyl groups are the same on both sides of the oxygen atom, then it is a simple or symmetrical ether, whereas if they are different, the ethers are called mixed or unsymmetrical ethers. A typical example of the first group is the solvent and anaesthetic diethyl ether, commonly referred to simply as "ether". Ethers are common in organic chemistry and even more prevalent in biochemistry, as they are common linkages in carbohydrates and lignin.

The haloalkanes are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalkanes are widely used commercially. They are used as flame retardants, fire extinguishants, refrigerants, propellants, solvents, and pharmaceuticals. Subsequent to the widespread use in commerce, many halocarbons have also been shown to be serious pollutants and toxins. For example, the chlorofluorocarbons have been shown to lead to ozone depletion. Methyl bromide is a controversial fumigant. Only haloalkanes that contain chlorine, bromine, and iodine are a threat to the ozone layer, but fluorinated volatile haloalkanes in theory may have activity as greenhouse gases. Methyl iodide, a naturally occurring substance, however, does not have ozone-depleting properties and the United States Environmental Protection Agency has designated the compound a non-ozone layer depleter. For more information, see Halomethane. Haloalkane or alkyl halides are the compounds which have the general formula "RX" where R is an alkyl or substituted alkyl group and X is a halogen.

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution (SN) is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule. The molecule that contains the electrophile and the leaving functional group is called the substrate.

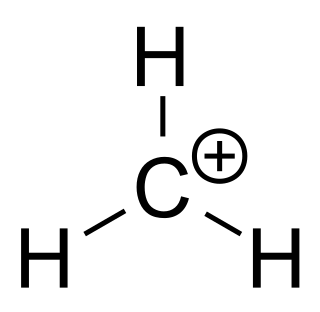

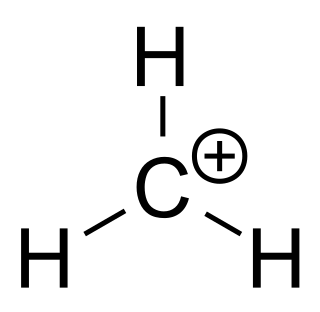

A carbocation is an ion with a positively charged carbon atom. Among the simplest examples are the methenium CH+

3, methanium CH+

5, acylium ions RCO+, and vinyl C

2H+

3 cations.

The Friedel–Crafts reactions are a set of reactions developed by Charles Friedel and James Crafts in 1877 to attach substituents to an aromatic ring. Friedel–Crafts reactions are of two main types: alkylation reactions and acylation reactions. Both proceed by electrophilic aromatic substitution.

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively charged, have an atom that carries a partial positive charge, or have an atom that does not have an octet of electrons.

In organic chemistry, an acyl chloride is an organic compound with the functional group −C(=O)Cl. Their formula is usually written R−COCl, where R is a side chain. They are reactive derivatives of carboxylic acids. A specific example of an acyl chloride is acetyl chloride, CH3COCl. Acyl chlorides are the most important subset of acyl halides.

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction which introduces one or more halogens into a chemical compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of polymers, drugs. This kind of conversion is in fact so common that a comprehensive overview is challenging. This article mainly deals with halogenation using elemental halogens. Halides are also commonly introduced using salts of the halides and halogen acids. Many specialized reagents exist for and introducing halogens into diverse substrates, e.g. thionyl chloride.

Organochlorine chemistry is concerned with the properties of organochlorine compounds, or organochlorides, organic compounds containing at least one covalently bonded atom of chlorine. The chloroalkane class includes common examples. The wide structural variety and divergent chemical properties of organochlorides lead to a broad range of names, applications, and properties. Organochlorine compounds have wide use in many applications, though some are of profound environmental concern, with TCDD being one of the most notorious.

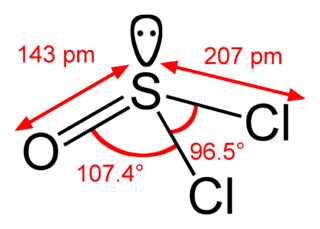

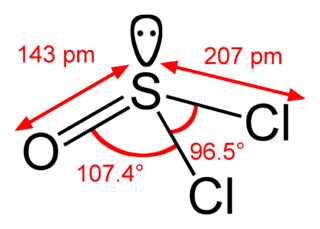

Thionyl chloride is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula SOCl2. It is a moderately volatile, colourless liquid with an unpleasant acrid odour. Thionyl chloride is primarily used as a chlorinating reagent, with approximately 45,000 tonnes per year being produced during the early 1990s, but is occasionally also used as a solvent. It is toxic, reacts with water, and is also listed under the Chemical Weapons Convention as it may be used for the production of chemical weapons.

The Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction is the chemical reaction of a trivalent phosphorus ester with an alkyl halide to form a pentavalent phosphorus species and another alkyl halide. The picture below shows the most common types of substrates undergoing the Arbuzov reaction; phosphite esters (1) react to form phosphonates (2), phosphonites (3) react to form phosphinates (4) and phosphinites (5) react to form phosphine oxides (6).

Hydrogen iodide (HI) is a diatomic molecule and hydrogen halide. Aqueous solutions of HI are known as hydroiodic acid or hydriodic acid, a strong acid. Hydrogen iodide and hydroiodic acid are, however, different in that the former is a gas under standard conditions, whereas the other is an aqueous solution of the gas. They are interconvertible. HI is used in organic and inorganic synthesis as one of the primary sources of iodine and as a reducing agent.

Isoamyl alcohol is a colorless liquid with the formula C

5H

12O, specifically (H3C–)2CH–CH2–CH2–OH. It is one of several isomers of amyl alcohol (pentanol). It is also known as isopentyl alcohol, isopentanol, or (in the IUPAC recommended nomenclature) 3-methyl-butan-1-ol. An obsolete name for it was isobutyl carbinol.

Grignard reagents or Grignard compounds are chemical compounds with the general formula R−Mg−X, where X is a halogen and R is an organic group, normally an alkyl or aryl. Two typical examples are methylmagnesium chloride Cl−Mg−CH3 and phenylmagnesium bromide (C6H5)−Mg−Br. They are a subclass of the organomagnesium compounds.

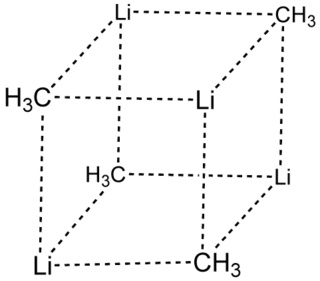

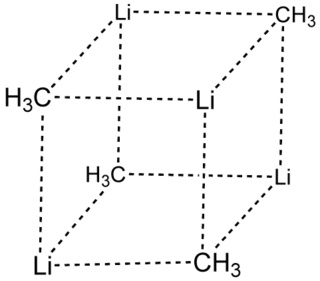

Methyllithium is the simplest organolithium reagent, with the empirical formula CH3Li. This s-block organometallic compound adopts an oligomeric structure both in solution and in the solid state. This highly reactive compound, invariably used in solution with an ether as the solvent, is a reagent in organic synthesis as well as organometallic chemistry. Operations involving methyllithium require anhydrous conditions, because the compound is highly reactive towards water. Oxygen and carbon dioxide are also incompatible with MeLi. Methyllithium is usually not prepared, but purchased as a solution in various ethers.

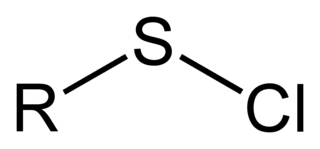

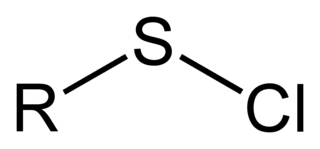

In organosulfur chemistry, a sulfenyl chloride is a functional group with the connectivity R−S−Cl, where R is alkyl or aryl. Sulfenyl chlorides are reactive compounds that behave as sources of RS+. They are used in the formation of RS−N and RS−O bonds. According to IUPAC nomenclature they are named as alkyl thiohypochlorites, i.e. esters of thiohypochlorous acid.

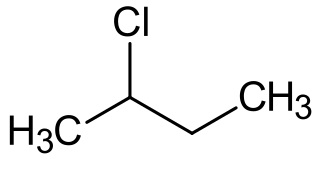

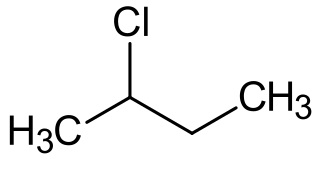

2-Chlorobutane is a compound with formula C4H9Cl. It is also called sec-butyl chloride. It is a colorless, volatile liquid at room temperature that is not miscible in water.

Imidoyl chlorides are organic compounds that contain the functional group RC(NR')Cl. A double bond exist between the R'N and the carbon centre. These compounds are analogues of acyl chloride. Imidoyl chlorides tend to be highly reactive and are more commonly found as intermediates in a wide variety of synthetic procedures. Such procedures include Gattermann aldehyde synthesis, Houben-Hoesch ketone synthesis, and the Beckmann rearrangement. Their chemistry is related to that of enamines and their tautomers when the α hydrogen is next to the C=N bond. Many chlorinated N-heterocycles are formally imidoyl chlorides, e.g. 2-chloropyridine, 2, 4, and 6-chloropyrimidines.