Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of ions across the cell membrane, controlling the flow of ions across secretory and epithelial cells, and regulating cell volume. Ion channels are present in the membranes of all cells. Ion channels are one of the two classes of ionophoric proteins, the other being ion transporters.

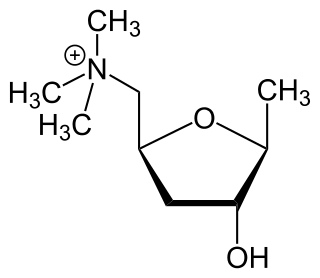

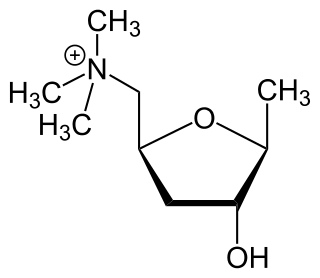

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Parts in the body that use or are affected by acetylcholine are referred to as cholinergic.

An acetylcholine receptor or a cholinergic receptor is an integral membrane protein that responds to the binding of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter.

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a kind of synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron less likely to generate an action potential. The opposite of an inhibitory postsynaptic potential is an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), which is a synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron more likely to generate an action potential. IPSPs can take place at all chemical synapses, which use the secretion of neurotransmitters to create cell-to-cell signalling. EPSPs and IPSPs compete with each other at numerous synapses of a neuron. This determines whether an action potential occurring at the presynaptic terminal produces an action potential at the postsynaptic membrane. Some common neurotransmitters involved in IPSPs are GABA and glycine.

An excitatory synapse is a synapse in which an action potential in a presynaptic neuron increases the probability of an action potential occurring in a postsynaptic cell. Neurons form networks through which nerve impulses travels, each neuron often making numerous connections with other cells of neurons. These electrical signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, and, if the total of excitatory influences exceeds that of the inhibitory influences, the neuron will generate a new action potential at its axon hillock, thus transmitting the information to yet another cell.

In electrophysiology, the threshold potential is the critical level to which a membrane potential must be depolarized to initiate an action potential. In neuroscience, threshold potentials are necessary to regulate and propagate signaling in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

A neuromuscular junction is a chemical synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, or nAChRs, are receptor polypeptides that respond to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Nicotinic receptors also respond to drugs such as the agonist nicotine. They are found in the central and peripheral nervous system, muscle, and many other tissues of many organisms. At the neuromuscular junction they are the primary receptor in muscle for motor nerve-muscle communication that controls muscle contraction. In the peripheral nervous system: (1) they transmit outgoing signals from the presynaptic to the postsynaptic cells within the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, and (2) they are the receptors found on skeletal muscle that receive acetylcholine released to signal for muscular contraction. In the immune system, nAChRs regulate inflammatory processes and signal through distinct intracellular pathways. In insects, the cholinergic system is limited to the central nervous system.

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, or mAChRs, are acetylcholine receptors that form G protein-coupled receptor complexes in the cell membranes of certain neurons and other cells. They play several roles, including acting as the main end-receptor stimulated by acetylcholine released from postganglionic fibers. They are mainly found in the parasympathetic nervous system, but also have a role in the sympathetic nervous system in the control of sweat glands.

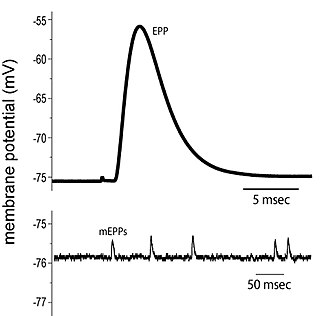

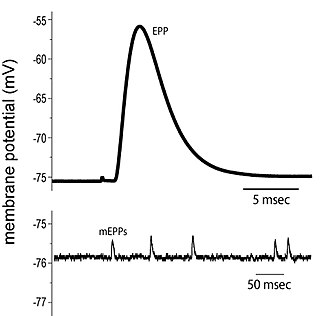

End plate potentials (EPPs) are the voltages which cause depolarization of skeletal muscle fibers caused by neurotransmitters binding to the postsynaptic membrane in the neuromuscular junction. They are called "end plates" because the postsynaptic terminals of muscle fibers have a large, saucer-like appearance. When an action potential reaches the axon terminal of a motor neuron, vesicles carrying neurotransmitters are exocytosed and the contents are released into the neuromuscular junction. These neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane and lead to its depolarization. In the absence of an action potential, acetylcholine vesicles spontaneously leak into the neuromuscular junction and cause very small depolarizations in the postsynaptic membrane. This small response (~0.4mV) is called a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) and is generated by one acetylcholine-containing vesicle. It represents the smallest possible depolarization which can be induced in a muscle.

Molecular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience that observes concepts in molecular biology applied to the nervous systems of animals. The scope of this subject covers topics such as molecular neuroanatomy, mechanisms of molecular signaling in the nervous system, the effects of genetics and epigenetics on neuronal development, and the molecular basis for neuroplasticity and neurodegenerative diseases. As with molecular biology, molecular neuroscience is a relatively new field that is considerably dynamic.

Neuromuscular-blocking drugs, or Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs), block transmission at the neuromuscular junction, causing paralysis of the affected skeletal muscles. This is accomplished via their action on the post-synaptic acetylcholine (Nm) receptors.

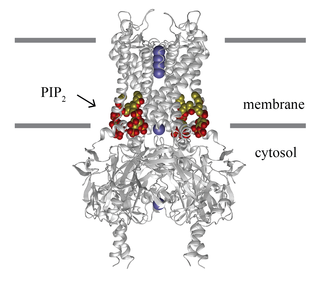

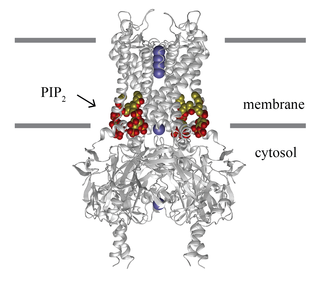

Inward-rectifier potassium channels (Kir, IRK) are a specific lipid-gated subset of potassium channels. To date, seven subfamilies have been identified in various mammalian cell types, plants, and bacteria. They are activated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). The malfunction of the channels has been implicated in several diseases. IRK channels possess a pore domain, homologous to that of voltage-gated ion channels, and flanking transmembrane segments (TMSs). They may exist in the membrane as homo- or heterooligomers and each monomer possesses between 2 and 4 TMSs. In terms of function, these proteins transport potassium (K+), with a greater tendency for K+ uptake than K+ export. The process of inward-rectification was discovered by Denis Noble in cardiac muscle cells in 1960s and by Richard Adrian and Alan Hodgkin in 1970 in skeletal muscle cells.

Margatoxin (MgTX) is a peptide that selectively inhibits Kv1.3 voltage-dependent potassium channels. It is found in the venom of Centruroides margaritatus, also known as the Central American Bark Scorpion. Margatoxin was first discovered in 1993. It was purified from scorpion venom and its amino acid sequence was determined.

Low-threshold spikes (LTS) refer to membrane depolarizations by the T-type calcium channel. LTS occur at low, negative, membrane depolarizations. They often follow a membrane hyperpolarization, which can be the result of decreased excitability or increased inhibition. LTS result in the neuron reaching the threshold for an action potential. LTS is a large depolarization due to an increase in Ca2+ conductance, so LTS is mediated by calcium (Ca2+) conductance. The spike is typically crowned by a burst of two to seven action potentials, which is known as a low-threshold burst. LTS are voltage dependent and are inactivated if the cell's resting membrane potential is more depolarized than −60mV. LTS are deinactivated, or recover from inactivation, if the cell is hyperpolarized and can be activated by depolarizing inputs, such as excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSP). LTS were discovered by Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1980s.

The G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRKs) are a family of lipid-gated inward-rectifier potassium ion channels which are activated (opened) by the signaling lipid PIP2 and a signal transduction cascade starting with ligand-stimulated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCRs in turn release activated G-protein βγ- subunits (Gβγ) from inactive heterotrimeric G protein complexes (Gαβγ). Finally, the Gβγ dimeric protein interacts with GIRK channels to open them so that they become permeable to potassium ions, resulting in hyperpolarization of the cell membrane. G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels are a type of G protein-gated ion channels because of this direct interaction of G protein subunits with GIRK channels. The activation likely works by increasing the affinity of the channel for PIP2. In high concentration PIP2 activates the channel absent G-protein, but G-protein does not activate the channel absent PIP2.

In neurophysiology, a dendritic spike refers to an action potential generated in the dendrite of a neuron. Dendrites are branched extensions of a neuron. They receive electrical signals emitted from projecting neurons and transfer these signals to the cell body, or soma. Dendritic signaling has traditionally been viewed as a passive mode of electrical signaling. Unlike its axon counterpart which can generate signals through action potentials, dendrites were believed to only have the ability to propagate electrical signals by physical means: changes in conductance, length, cross sectional area, etc. However, the existence of dendritic spikes was proposed and demonstrated by W. Alden Spencer, Eric Kandel, Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1960s and a large body of evidence now makes it clear that dendrites are active neuronal structures. Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels giving them the ability to generate action potentials. Dendritic spikes have been recorded in numerous types of neurons in the brain and are thought to have great implications in neuronal communication, memory, and learning. They are one of the major factors in long-term potentiation.

Cellular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience concerned with the study of neurons at a cellular level. This includes morphology and physiological properties of single neurons. Several techniques such as intracellular recording, patch-clamp, and voltage-clamp technique, pharmacology, confocal imaging, molecular biology, two photon laser scanning microscopy and Ca2+ imaging have been used to study activity at the cellular level. Cellular neuroscience examines the various types of neurons, the functions of different neurons, the influence of neurons upon each other, and how neurons work together.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.

KCNQ2 encephalopathy typically presents with tonic seizures from the first week of life. The seizures can be frequent and often difficult to treat. Seizures can resolve within months or years but can impair the development of several domains such as motor, social, cognitive and language.