Related Research Articles

Human rights are universally recognized moral principles or norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both national and international laws. These rights are considered inherent and inalienable, meaning they belong to every individual simply by virtue of being human, regardless of characteristics like nationality, ethnicity, religion, or socio-economic status. They encompass a broad range of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, such as the right to life, freedom of expression, protection against enslavement, and right to education.

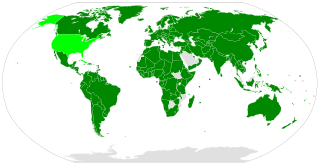

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 1976. It commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to all individuals including those living in Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories. The rights include labour rights, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. As of February 2024, the Covenant has 172 parties. A further four countries, including the United States, have signed but not ratified the Covenant.

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

The International Bill of Human Rights was the name given to UN General Assembly Resolution 217 (III) and two international treaties established by the United Nations. It consists of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights with its two Optional Protocols and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The two covenants entered into force in 1976, after a sufficient number of countries had ratified them.

The right to health is the economic, social, and cultural right to a universal minimum standard of health to which all individuals are entitled. The concept of a right to health has been enumerated in international agreements which include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. There is debate on the interpretation and application of the right to health due to considerations such as how health is defined, what minimum entitlements are encompassed in a right to health, and which institutions are responsible for ensuring a right to health.

Human Rights Quarterly (HRQ) is a quarterly academic journal founded by Richard Pierre Claude in 1982 covering human rights. The journal is intended for scholars and policymakers and follows recent developments from both governments and non-governmental organizations. It includes research in policy analysis, book reviews, and philosophical essays. The journal is published by the Johns Hopkins University Press and the editor-in-chief is Bert B. Lockwood, Jr..

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) is a United Nations treaty body entrusted with overseeing the implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). It is composed of 18 experts.

The right to food, and its variations, is a human right protecting the right of people to feed themselves in dignity, implying that sufficient food is available, that people have the means to access it, and that it adequately meets the individual's dietary needs. The right to food protects the right of all human beings to be free from hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition. The right to food implies that governments only have an obligation to hand out enough free food to starving recipients to ensure subsistence, it does not imply a universal right to be fed. Also, if people are deprived of access to food for reasons beyond their control, for example, because they are in detention, in times of war or after natural disasters, the right requires the government to provide food directly.

Decree 1775 was signed into Brazilian law by President Fernando Henrique Cardoso on January 8, 1996. The decree changed the steps FUNAI was required to follow to demarcate indigenous lands, effectively making the process more complicated and allowing for more interference from commercial interests. Individuals or companies were allowed from the beginning of the demarcation process until 90 days after FUNAI issued their report to submit an appeal showing that the contested lands do not meet the qualifications of indigenous lands as stated in the constitution. The decree also placed the final decision in the hands of the Minister of Justice, which left the fate of indigenous lands vulnerable to various political ideologies. The government claimed that allowing people to contest indigenous lands during the demarcation process would prevent any future challenges of completed lands on the basis of unconstitutionality. The decree was widely contested as a violation of indigenous rights, earning the nickname of the "Genocide Decree," due to the power it gave to commercial interests to exploit Indian lands. By April 1996, FUNAI had received over 500 appeals for over 40 indigenous territories that were in the process of being demarcated. FUNAI followed procedure and submitted its official opinion to the Ministry of Justice, rejecting the appeals that were brought against the indigenous lands. Justice Nelson Jobim sided with FUNAI on all except eight territories, ordering further investigation.

The right to development is a human right that recognizes every human right for constant improvement of well-being. It was recognized by the United Nation as an international human right in 1986.

The Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is an international treaty establishing complaint and inquiry mechanisms for the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 2008, and opened for signature on 24 September 2009. As of February 2024, the Protocol has 46 signatories and 29 state parties. It entered into force on 5 May 2013.

The right to housing is the economic, social and cultural right to adequate housing and shelter. It is recognized in some national constitutions and in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The right to housing is regarded as a freestanding right in the International human rights law which was clearly in the 1991 General Comment on Adequate Housing by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The aspect of the right to housing under ICESCR include: availability of services, infrastructure, material and facilities; legal security of tenure; habitability; accessibility; affordability; location and cultural adequacy.

Rights-based approach to development is promoted by many development agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to achieve a positive transformation of power relations among the various development actors. This practice blurs the distinction between human rights and economic development. There are two stakeholder groups in rights-based development—the rights holders and the duty bearers. Rights-based approaches aim at strengthening the capacity of duty bearers and empower the rights holders.

The Voluntary Guidelines to support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security, also known as the Right to Food Guidelines, is a document adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2004, with the aim of guiding states to implement the right to food. It is not legally binding, but directed to states' obligations to the right to food under international law. In specific, it is directed towards States Parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and to States that still have to ratify it.

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. A third-generation human rights instrument, the Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discrimination and the promotion of understanding among all races. The Convention also requires its parties to criminalize hate speech and criminalize membership in racist organizations.

Development is a human right that belongs to everyone, individually and collectively. Everyone is “entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized,” states the groundbreaking UN Declaration on the Right to Development, proclaimed in 1986.

The family rights or right to family life are the rights of all individuals to have their established family life respected, and to start, have and maintain a family. This right is recognised in a variety of international human rights instruments, including Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 23 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Ashfaq Khalfan is an international jurist in human rights law, Director of the Law and Policy Programme at Amnesty International, and Chair of the Board of Governors of the Centre for International Sustainable Development Law.

UN General Assembly Resolution 60/147, the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law, is a United Nations Resolution about the rights of victims of international crimes. It was adopted by the General Assembly on 16 December 2005 in its 60th session. According to the preamble, the purpose of the Resolution is to assist victims and their representatives to remedial relief and to guide and encourage States in the implementation of public policies on reparations.

Extraterritorial Obligations (ETOs) are obligations in relation to the acts and omissions of a state, within or beyond its territory, that have effects on the enjoyment of human rights outside of that state's territory.

References

- ↑ Leckie, Scott; Gallanger, Anne (2006). Economic, social and cultural rights: a legal resource guide. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-0-8122-3916-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Maastricht". Human Rights Library University of Minnesota

- ↑ United Nations Economic and Social Council Session 24 Agenda item Day of General Discussion Organized in Cooperation with the World Iintellectual Property Organization (WIPO)E/C.12/2000/13 2 October 2000. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "Urban Morgan Institute of Human Rights | UC College of Law". www.law.uc.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- 1 2 Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 708. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 709. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- 1 2 Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 710. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ "OHCHR - Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action". www.ohchr.org. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 711–712. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 712. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 714–715. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- 1 2 Heyns, Christof; Brand, Danie (1998). "Introduction to socio-economic rights in the South African Constitution". Law, Democracy & Development. 2 (2): 158.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 715. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 716. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 717. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 718. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 720. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- 1 2 Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 724. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 724–725. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 725. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- 1 2 Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 726. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 727. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ "Bangalore Declaration and Plan of Action | ICJ". www.icj.org. 1995-10-25. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 728. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Dankwa, Victor; Flinterman, Cees; Leckie, Scott (August 1998). "Commentary on the Maastricht Guidelines". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (3): 729. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0028. JSTOR 762784.

- ↑ Economic, social and cultural rights : handbook for national human rights institutions. United Nations. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. New York: United Nations. 2005. ISBN 9211541638. OCLC 62325557.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Heyns, Christof; Brand, Danie (1998). "Introduction to socio-economic rights in the South African Constitution". Law, Democracy & Development. 2 (2): 158 and 160.