Related Research Articles

A heterotroph is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but not producers. Living organisms that are heterotrophic include all animals and fungi, some bacteria and protists, and many parasitic plants. The term heterotroph arose in microbiology in 1946 as part of a classification of microorganisms based on their type of nutrition. The term is now used in many fields, such as ecology in describing the food chain.

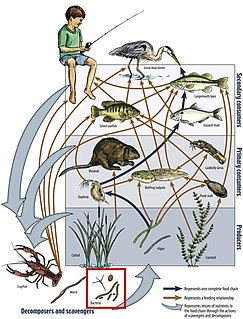

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one of two categories called trophic levels: 1) the autotrophs, and 2) the heterotrophs. To maintain their bodies, grow, develop, and to reproduce, autotrophs produce organic matter from inorganic substances, including both minerals and gases such as carbon dioxide. These chemical reactions require energy, which mainly comes from the Sun and largely by photosynthesis, although a very small amount comes from bioelectrogenesis in wetlands, and mineral electron donors in hydrothermal vents and hot springs. These trophic levels are not binary, but form a gradient that includes complete autotrophs, which obtain their sole source of carbon from the atmosphere, mixotrophs, which are autotrophic organisms that partially obtain organic matter from sources other than the atmosphere, and complete heterotrophs that must feed to obtain organic matter.

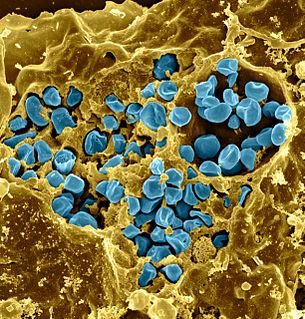

Phagocytosis is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle, giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is called a phagocyte.

In ecology, a biological interaction is the effect that a pair of organisms living together in a community have on each other. They can be either of the same species, or of different species. These effects may be short-term, like pollination and predation, or long-term; both often strongly influence the evolution of the species involved. A long-term interaction is called a symbiosis. Symbioses range from mutualism, beneficial to both partners, to competition, harmful to both partners. Interactions can be indirect, through intermediaries such as shared resources or common enemies. This type of relationship can be shown by net effect based on individual effects on both organisms arising out of relationship.

This glossary of ecology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts in ecology and related fields. For more specific definitions from other glossaries related to ecology, see Glossary of biology, Glossary of evolutionary biology, and Glossary of environmental science.

Detritivores are heterotrophs that obtain nutrients by consuming detritus. There are many kinds of invertebrates, vertebrates and plants that carry out coprophagy. By doing so, all these detritivores contribute to decomposition and the nutrient cycles. They should be distinguished from other decomposers, such as many species of bacteria, fungi and protists, which are unable to ingest discrete lumps of matter, but instead live by absorbing and metabolizing on a molecular scale. The terms detritivore and decomposer are often used interchangeably, but they describe different organisms. Detritivores are usually arthropods and help in the process of remineralization. Detritivores perform the first stage of remineralization, by fragmenting the dead plant matter, allowing decomposers to perform the second stage of remineralization.

Francisella tularensis is a pathogenic species of Gram-negative coccobacillus, an aerobic bacterium. It is nonspore-forming, nonmotile, and the causative agent of tularemia, the pneumonic form of which is often lethal without treatment. It is a fastidious, facultative intracellular bacterium, which requires cysteine for growth. Due to its low infectious dose, ease of spread by aerosol, and high virulence, F. tularensis is classified as a Tier 1 Select Agent by the U.S. government, along with other potential agents of bioterrorism such as Yersinia pestis, Bacillus anthracis, and Ebola virus. When found in nature, Francisella tularensis can survive for several weeks at low temperatures in animal carcasses, soil, and water. In the laboratory, F. tularensis appears as small rods, and is grown best at 35–37 °C.

The soil food web is the community of organisms living all or part of their lives in the soil. It describes a complex living system in the soil and how it interacts with the environment, plants, and animals.

Optimal foraging theory (OFT) is a behavioral ecology model that helps predict how an animal behaves when searching for food. Although obtaining food provides the animal with energy, searching for and capturing the food require both energy and time. To maximize fitness, an animal adopts a foraging strategy that provides the most benefit (energy) for the lowest cost, maximizing the net energy gained. OFT helps predict the best strategy that an animal can use to achieve this goal.

An ecological pyramid is a graphical representation designed to show the biomass or bioproductivity at each trophic level in a given ecosystem.

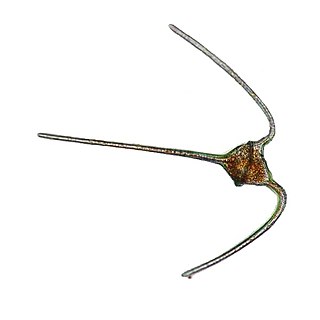

The genus Ceratium is restricted to a small number of freshwater dinoflagellate species. Previously the genus contained also a large number of marine dinoflagellate species. However, these marine species have now been assigned to a new genus called Tripos. Ceratium dinoflagellates are characterized by their armored plates, two flagella, and horns. They are found worldwide and are of concern due to their blooms.

Karenia is a genus that consists of unicellular, photosynthetic, planktonic organisms found in marine environments. The genus currently consists of 12 described species. They are best known for their dense toxic algal blooms and red tides that cause considerable ecological and economical damage; some Karenia species cause severe animal mortality. One species, Karenia brevis, is known to cause respiratory distress and neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP) in humans.

Ecological efficiency describes the efficiency with which energy is transferred from one trophic level to the next. It is determined by a combination of efficiencies relating to organismic resource acquisition and assimilation in an ecosystem.

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide, generally using energy from light (photosynthesis) or inorganic chemical reactions (chemosynthesis). They convert an abiotic source of energy into energy stored in organic compounds, which can be used by other organisms. Autotrophs do not need a living source of carbon or energy and are the producers in a food chain, such as plants on land or algae in water. Autotrophs can reduce carbon dioxide to make organic compounds for biosynthesis and as stored chemical fuel. Most autotrophs use water as the reducing agent, but some can use other hydrogen compounds such as hydrogen sulfide.

A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comprise more than half of all microscopic plankton. There are two types of eukaryotic mixotrophs: those with their own chloroplasts, and those with endosymbionts—and those that acquire them through kleptoplasty or by enslaving the entire phototrophic cell.

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions from sub-disciplines and related fields, see Glossary of genetics, Glossary of evolutionary biology, Glossary of ecology, and Glossary of scientific naming, or any of the organism-specific glossaries in Category:Glossaries of biology.

Reticulomyxa is a monospecific genus of freshwater foraminiferans. The type species is the unicellular Reticulomyxa filosa. It is found in freshwater environments as well as moist environments, like decomposing matter and damp soils. The heterotrophic naked foraminiferan can feed on microbes as well has larger organisms and is able to be sustained in culture by supplemented nutrients such as wheat germ and oats. The large, multinucleate foraminferan is characteristic for its lack of test and named for the network of connecting pseudopodia surrounding its central body mass. The organism has unique bidirectional cytoplasmic streaming throughout the anastomosing pseudopodia that is some of the fastest reported organelle transport observed. Reticulomyxa was first described in 1949 and is commonly used as a model organism for the unique transport of organelles throughout the cytoplasm of pseudopodia by cytoskeletal mechanisms. Only asexual reproduction of this genus has been observed in culture, but the genome possesses genes related to meiosis suggesting it is capable of sexually reproductive life stages.

Picozoa, Picobiliphyta, Picobiliphytes, or Biliphytes are protists of a phylum of marine unicellular heterotrophic eukaryotes with a size of less than about 3 micrometers. They were formerly treated as eukaryotic algae and the smallest member of photosynthetic picoplankton before it was discovered they don't perform photosynthesis. The first species identified therein is Picomonas judraskeda. They probably belong in the Archaeplastida as sister of the Rhodophyta.

Oxyrrhis marina is a species of dinoflagellates with flagella. A marine heterotroph, it is found in much of the world.

Dinophysis acuminata is a marine plankton species of dinoflagellates that is found in coastal waters of the north Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The genus Dinophysis includes both phototrophic and heterotrophic species. D. acuminata is one of several phototrophic species of Dinophysis classed as toxic, as they produce okadaic acid which can cause diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP). Okadiac acid is taken up by shellfish and has been found in the soft tissue of mussels and the liver of flounder species. When contaminated animals are consumed, they cause severe diarrhoea. D. acuminata blooms are constant threat to and indication of diarrhoeatic shellfish poisoning outbreaks.