Lwa, also called loa, are spirits in the African diasporic religion of Haitian Vodou and Dominican Vudú. They have also been incorporated into some revivalist forms of Louisiana Voodoo. Many of the lwa derive their identities in part from deities venerated in the traditional religions of West Africa, especially those of the Fon and Yoruba.

Baron Samedi, also written Baron Samdi, Bawon Samedi or Bawon Sanmdi, is one of the lwa of Haitian Vodou. He is a lwa of the dead, along with Baron's numerous other incarnations Baron Cimetière, Baron La Croix and Baron Criminel.

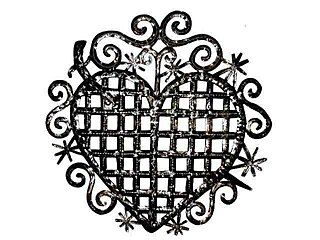

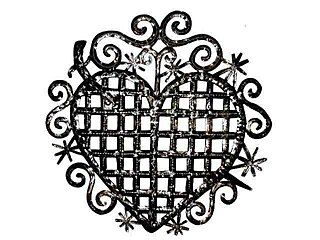

Èzili Dantò or Erzulie Dantor is the main loa or senior spirit of the Petro family in Haitian Vodou. Ezili Danto, or Èzili Dantò, is the "manifestation of Erzulie, the divinity of love." It is said that Ezili Danto has a dark complexion and is maternal in nature. The Ezili are feminine spirits in Haitian Vodou that personify womanhood. The Erzulie is a goddess, spirit, or loa of love in Haitian Voudou. She has several manifestations or incarnations, but most prominent and well-known manifestations are Lasirenn, Erzulie Freda, and Erzulie Dantor. There are spelling variations of Erzulie, the other being Ezili. They are English interpretations of a Creole word, but do not differ in meaning.

Haitian mythology consists of many folklore stories from different time periods, involving sacred dance and deities, all the way to Vodou. Haitian Vodou is a syncretic mixture of Roman Catholic rituals developed during the French colonial period, based on traditional African beliefs, with roots in Dahomey, Kongo and Yoruba traditions, and folkloric influence from the indigenous Taino peoples of Haiti. The lwa, or spirits with whom Vodou adherents work and practice, are not gods but servants of the Supreme Creator Bondye. A lot of the Iwa identities come from deities formed in the West African traditional regions, especially the Fon and Yoruba. In keeping with the French-Catholic influence of the faith, Vodou practioneers are for the most part monotheists, believing that the lwa are great and powerful forces in the world with whom humans interact and vice versa, resulting in a symbiotic relationship intended to bring both humans and the lwa back to Bondye. "Vodou is a religious practice, a faith that points toward an intimate knowledge of God, and offers its practitioners a means to come into communion with the Divine, through an ever evolving paradigm of dance, song and prayers."

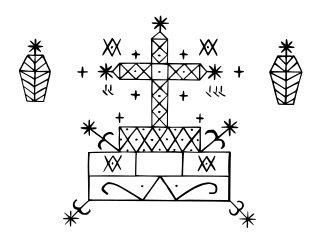

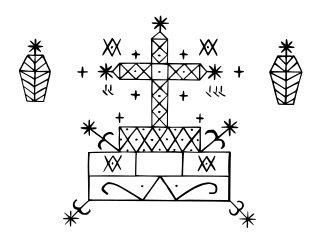

A veve is a religious symbol commonly used in different branches of Vodun throughout the African diaspora, such as Haitian Vodou and Louisiana Voodoo. The veve acts as a "beacon" for the lwa, and will serve as a lwa's representation during rituals.

Oungan is the term for a male priest in Haitian Vodou. The term is derived from Gbe languages. The word hounnongan means chief priest. Hounnongan or oungans are also known as makandals.

Homosexuality in Haitian Vodou is religiously acceptable and homosexuals are allowed to participate in all religious activities. However, in West African countries with major conservative Christian and Islamic views on LGBTQ people, the attitudes towards them may be less tolerant if not openly hostile and these influences are reflected in African diaspora religions following Atlantic slave trade which includes Haitian Vodou.

Haitian Vodou is an African diasporic religion that developed in Haiti between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism between several traditional religions of West and Central Africa and Roman Catholicism. There is no central authority in control of the religion and much diversity exists among practitioners, who are known as Vodouists, Vodouisants, or Serviteurs.

Marilyn Jensen Houlberg was a professor, art historian, anthropologist, photographer, and curator. She was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. Houlberg traveled extensively, conducting art historical and anthropological research in countries across the Caribbean and western Africa. She is known for curating exhibitions based on the religious icons and visual practices of Haitian Vodou and her anthropological research on the culture of the Yoruba people in southwestern Nigeria. Her photography archives and visual art collections are housed in various institutions throughout the United States. She was Professor Emeritus of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she taught for over twenty years.

Haitian art is a complex tradition, reflecting African roots with strong Indigenous, American and European aesthetic and religious influences. It is an important expression of Haitian culture and history.

Haitian Vodou art is art related to the Haitian Vodou religion. This religion has its roots in West African traditional religions brought to Haiti by slaves, but has assimilated elements from Europe and the Americas and continues to evolve. The most distinctive Vodou art form is the drapo Vodou, an embroidered flag often decorated with sequins or beads, but the term covers a wide range of visual art forms including paintings, embroidered clothing, clay or wooden figures, musical instruments and assemblages. Since the 1950s there has been growing demand for Vodou art by tourists and collectors.

Pierrot Barra (1942–1999) was a Haitian Vodou artist and priest, who was president of a Bizango society. He was well-known for his use of diverse materials to create “Vodou Things,” which functioned as charms or altars for the Vodou religion.

Ersulie Mompremier is a Haitian artist. She is married to Madsen Mompremier and in 1978 began studying painting with him. Mompremier's artworks highlights daily Haitian life in direct contrast to her husband's compositions. Along with being a painter she is a community worker in Haiti.

Pauleus Vital was a Haitian artist. He was born in Jacmel, in October 1917. He grew up learning to build boats, and cabinets. At age 21 he moved to Port-au-Prince to further his building career. At age 38, Vital started to paint, after his half-brother Prefete Duffaut, introduced him to Centre d’Art. He spent 3 years at Centre d’Art, then moved back to Jacmel in 1959. Much of the motivation for his work comes from his home by the river in Jacmel. His work consists of detailed paintings, of everything from Haitian courtyards, countryside’s, and subterranean Vodou ceremonies. His paintings are relatively small and vary in size from around 24”x20” and up to 24” x 48”. He died on June 18, 1984, at age 66, while undergoing heart surgery.

Joseph Wilfrid Daleus, sometimes called Joseph Daleus, or Wilfrid Daleus, was a Haitian painter born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Theard Aladin was a Haitian self-taught artist, noted for his artwork depicting Haitian life and use of bright colors in paintings.

Mireille Delismé,, is a Haitian drapo Vodou artist from Léogâne, Haiti.

Voodoo: Truth and Fantasy is a 1993 illustrated monograph on Haitian Vodou. Written by the Haitian sociologist of religion Laënnec Hurbon, and published in pocket format by Éditions Gallimard as the 190th volume in their 'Découvertes' collection.

Irony of Negro Policeman is a painting created by American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1981. It depicts a black figure as police officer.